|

Nestled in the rough mountainous country west of the cities of Nogales, Arizona, and Nogales, Mexico, Boundary Monument 127 is a significant geographic turning point for the U.S.-Mexican border - and is located on the WRONG spot!

4 Comments

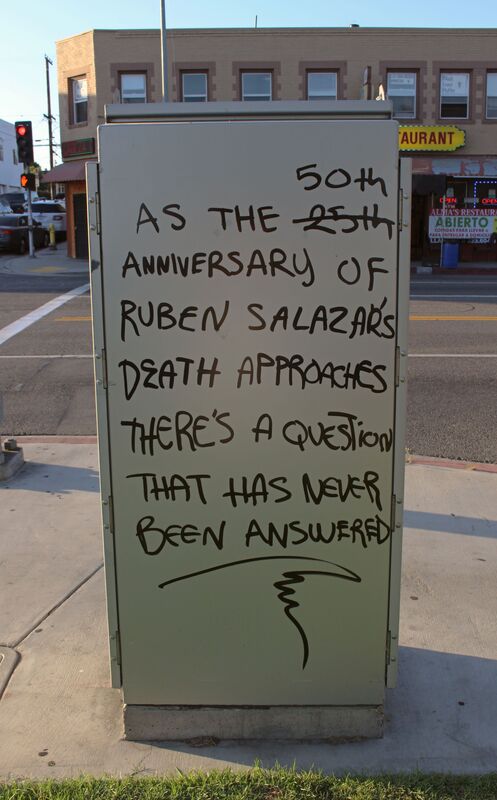

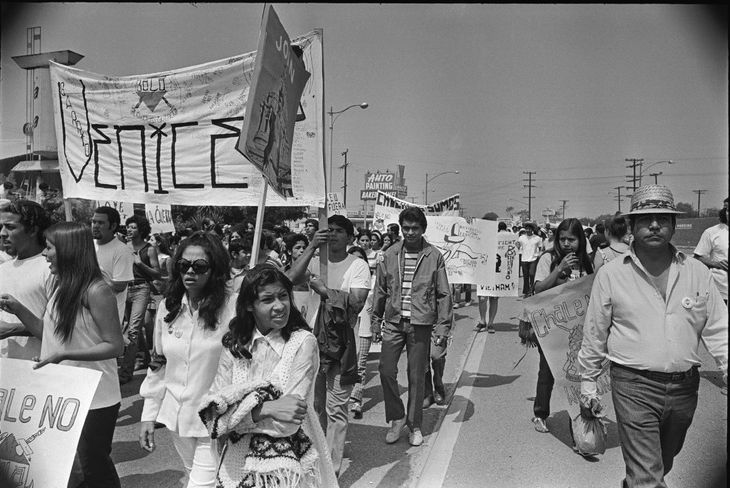

On August 29, 1970, East Los Angeles became the stage for one of the most captivating moments of the Vietnam War’s home front – the National Chicano Moratorium protests against the disproportionate loss of Mexican American servicemen in the war. The largest protest of the 1960s/1970s Chicano movement, nearly 20,000-30,000 people participated in the Moratorium. However, its message was muffled by violence between the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department and demonstrators leading to 150 arrests and four deaths, including journalist Rubén Salazar.

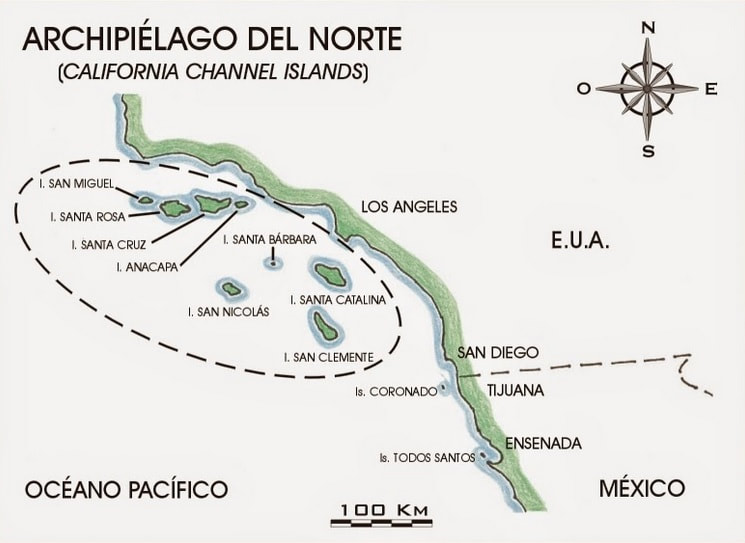

Retrace the route of the Chicano Moratorium through East Los Angeles here and rediscover Mexican American protestors’ cries for racial justice: “Chale no, we won’t go – bring the ‘carnales’ home!” – and then leave your thoughts below! From August 30-Septemeber 22, 1972, a group of young Chicana and Chicano activists known as the Brown Berets staged an occupation of the Santa Catalina Island to protest against the discrimination and police abuse of Mexican people in the U.S. Southwest. The Brown Berets brought dramatic attention to their protest by basing it on the fact that the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo which ended the U.S.-Mexico War did not specifically state Mexico gave up Catalina and the Channel Islands of the Archipelago of the North to the U.S. By encamping at a cliffside camp they named “Campo Tecolote” the Brown Berets hoped to raise the U.S. public’s awareness of anti-Mexican racism and inspire cultural pride among Mexican Americans. [1]

The California Channel Islands located off the coast of the Greater Los Angeles area are today known for their rich ecological and recreational heritage, but were not were not mentioned in Article V of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) which outlined the U.S.-Mexico border after Mexico surrendered California to the U.S. Indeed, a strict reading of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo suggested to many groups – indigenous Chumash people, White Americans, and Mexican people – that the islands were still Mexican national territory. Map by Víctor Busteros Angeles, “Día 23, jueves 5-05. Rumbo a Coronado,” Expedición al México de Ultramar (Feb. 13, 2015), (http://mexicodeultramar.blogspot.com/2015_02_13_archive.html).

The hardening U.S.-Mexico border of the 2010s has been increasingly defined by walls and division, but symbolic bridges continue to tie the two countries’ people together. One such recent link is the newest bridge on the U.S.-Mexican border, the Cross Border Xpress (CBX) linking the Tijuana International Airport (TIJ) in Mexico with a passenger check-in terminal in San Diego, California, making TIJ the only airport in the world with terminals in two different countries. Open since 2015, the CBX (aka, “La Puerta de las Californias”) symbolizes the two countries’ ability (and inability) to cooperate. Grab onto your luggage as we rush across the CBX’s history to our flight in Tijuana!

A small bird rests on a tree along a quiet stretch of the Río Grande in South Texas/Tamaulipas. The border river has a great emotional presence in both the U.S. and Mexican imagination, often leading to the belief that the entire river is a dangerous haven of crime. Although the Río Grande has its human-caused dangers, its cultural and natural history is much, much deeper than what is often presented in the news. Currently much of this quiet riverine forest is in danger of being destroyed by the U.S.’s border wall project. In a coming Nomadic Border photo essay, we will explore some of this rich history at the peaceful riverside Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge in Texas.

A tall shining metallic arch rises above the busy streets and rolling hills of Tijuana, Baja California, giving Mexico’s westernmost city an icon to welcome visitors and to symbolize its modernity. It is called by various names, including the Arco del Milenio (Millennium Arch) or Arco de Tijuana, but officially the arch is known as the Reloj Monumental de Tijuana (Tijuana Monumental Clock). The arch has been controversial since its construction but has also become one of the city’s most important symbols in the 21st Century. [1]

For many, the U.S.-Mexico border summons images of barrier walls and binational border towns set in arid desert landscapes. However, on January 2, 2019, snow blanketed the international boundary between Nogales, Arizona, USA, and Heroica Nogales, Sonora, Mexico. For a few hours the borderlands were a winter wonderland.

Art is part of the discussion. The border is an issue that art can say a lot about." Along the U.S-Mexican border various artists, using a variety of art forms, have worked to encourage the general public to reflect on the social problems caused by the border’s existence. Among the most noteworthy issues this art explores are transnational migration as well as the use of government force (such as the U.S. Border Patrol) to build up the border. The work of Nogales, Sonora, artists Alberto Morackis and Guadalupe Serrano bears witness to how public art can contribute to a greater awareness of the border’s social problems.

Each year Mexican people celebrate the 16th of September in commemoration of the 1810 start of what became the Mexican independence movement. The colorful patriotic festival is celebrated not only within Mexican national boundaries, but also on the other side of its northern border wherever great concentrations of Mexican communities are found. In Los Angeles, California the demographic and cultural strength of the Mexican community – the second largest in the world after Mexico City – makes celebrating the annual “fiestas patrias” an indispensable local tradition. A colorful ceramic mural located in the historic heart of L.A. titled El Grito (“The Cry”) celebrates Mexico’s independence and as well as the heritage of the city’s vibrant Mexican American community.

|

Carlos Parra

U.S.-Mexican, Latino, and Border Historian Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed