THE 1972 BROWN BERET INVASION OF CATALINA ISLAND:

A CHICANO HOMELAND IN MEXICO’S LOST ARCHIPELAGO

Text and original photography by Carlos Francisco Parra

January 20, 2020 (updated June 7, 2020)

|

“We’re being invaded! Mexican soldiers are claiming the island!”a woman exclaimed as a group in brown military uniforms raised a large Mexican flag over the town of Avalon on Santa Catalina Island. Observing the group through binoculars, residents worried that the Mexican Army was invading their tourist island off the coast of Southern California. Responding to frantic emergency calls, Los Angeles County Sheriffs approached the group. David Sánchez, the group’s leader, explained that Santa Catalina and the archipelago it belonged to – the California Channel Islands – was Mexican land “now occupied by many U.S. citizens.” The U.S. was “going to take these islands away from Mexico without the knowledge of the public” unless Sánchez and the Brown Berets acted. [2]

|

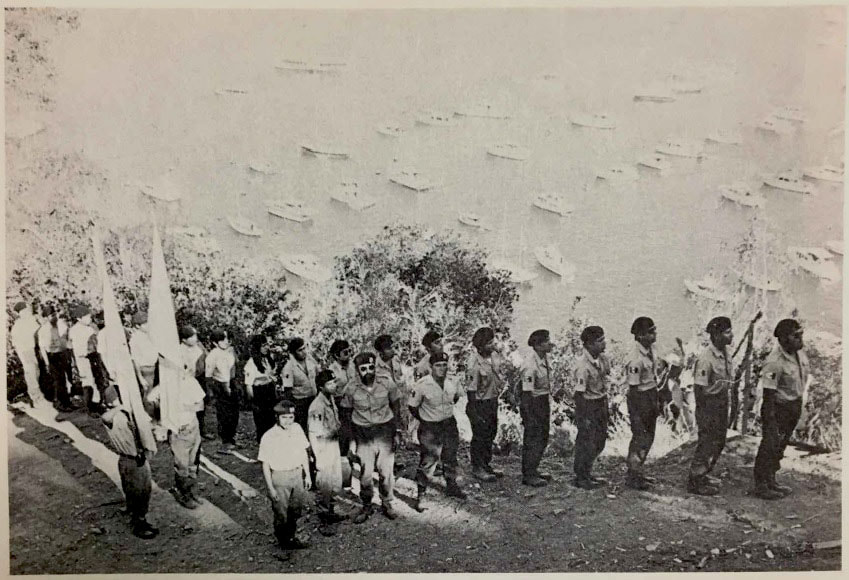

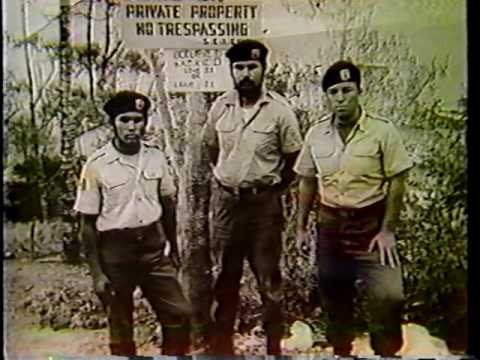

Sánchez and the 25 young men and women who accompanied him during the August 30-September 22, 1972 Brown Beret occupation of Catalina Island were Mexican Americans (Chicanos) who sought to bring attention to the injustices and discrimination Mexican people faced in the U.S.The Brown Berets justified what they called their “invasion” of Catalina on the fact that the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in which Mexico surrendered California (and much of western North America) to the U.S. did not specify that it also gave the islands to the U.S. According to the Brown Berets, Santa Catalina and the seven other Channel Islands (or Archipelago of the North) were still part of Mexico. The young Brown Berets’ struggle occupying one of the islands in Mexico’s lost archipelago embodies the complexities and consequences of the history of the U.S.-Mexican border.

Quick Summary:

- Brown Berets invaded Santa Catalina Island from August 30-Sept. 22, 1972

- As a Chicano activist group, the Brown Berets wanted to bring attention to anti-Mexican discrimination in U.S.

- Brown Berets based their demonstration on the argument that Mexico did not surrender the Channel Islands to the U.S. in the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Santa Catalina Island’s Historical Background

|

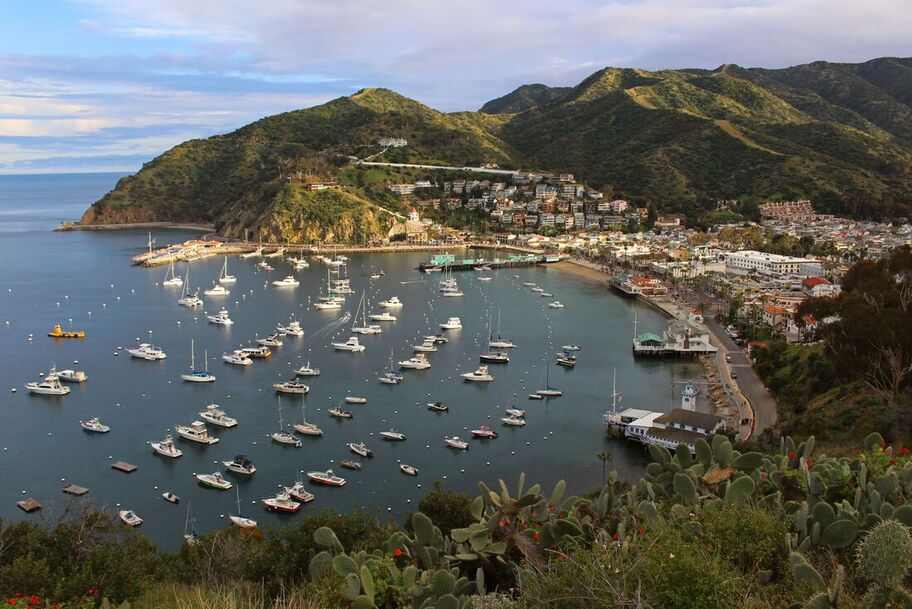

Located 22 miles (35 km) southwest of the Port of Los Angeles, Santa Catalina Island is known as a tourist destination for Southern Californians. Long before modern day-trippers began visiting the island via ferry, Tongva (Gabrielino) indigenous people of the Los Angeles area lived on Catalina (Pimu) Island and maintained economic and cultural ties to the mainland Tongva. Spanish explorers first sighted the island in fall 1542 and gave it its current name in 1602. Affected by epidemics and other pressures from the Spanish colonization of California, the Pimu Tongva abandoned their island in the 1820s, relocating to missions and ranches in near Los Angeles. In one of his final acts as governor of Mexican Alta California, Pio de Jesus Pico gave all of Catalina as a land grant to Thomas Robbins, a local sailor and naturalized Mexican citizen (1846). [3]

|

|

The island changed hands numerous times in the following century, its most famous owner being chewing gum industrialist William Wrigley Jr. who successfully expanded on existing efforts to develop Catalina into a tourist destination after buying the Santa Catalina Island Company in 1919. Under the Wrigleys, the island (especially the town of Avalon) became an important tourist center. Many Mexican-immigrant and Mexican American workers moved to Catalina during this time to work in the ranching and tourist businesses. By 1972 at least 300 Mexican/Mexican American people lived in Avalon. [4]

|

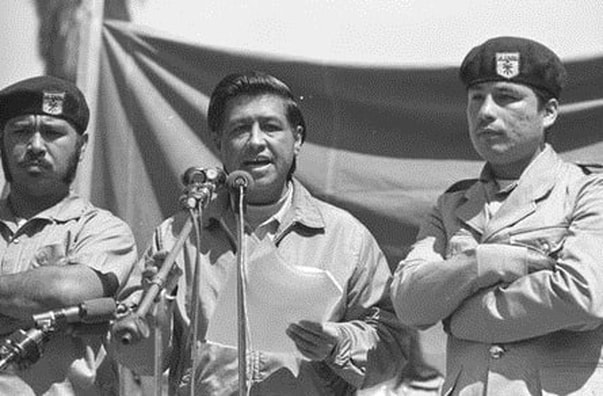

The Brown Beret “invasion” of Santa Catalina Island was part of the Chicano Movementof the 1960s and 1970s. To identify as a Chicana or Chicano (a politically conscious Mexican American) meant reaffirming one’s cultural heritage and resisting anti-Mexican discrimination in the U.S.Whether protesting against discriminatory labor conditions (as César Chávez and Dolores Huerta did in their United Farm Workers movement) or opposing the Vietnam War, Chicanos fought against racist abuses of Mexican people. The Berets’ brown uniforms and military discipline raised their visibility as they held demonstrations in border states against police brutality and economic inequality. Often the Berets acted as security escorts for other groups during protests.

The Chicano Movement had been losing strength when David Sánchez, co-founder and Prime Minister of the Brown Berets, convinced the group to invade Catalina Island and inspire renewed Chicano activism. As Sánchez recalled in his book Expedition Through Aztlan (1978), the group’s mission was “to land and occupy this area as a symbol of the Chicano Movement.” [8] To bring attention to the injustices faced by Mexicans in the U.S., the Berets would assert that the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo – which ended the 1846-1848 U.S.-Mexico War and formalized Mexico’s loss of California and most of western North America – did not include the Channel Islands. Article V of the treaty defined the U.S.-Mexico border, affirming it ended on “a point on the coast of the Pacific Ocean”south of San Diego Bay. Given Article V’s ambiguity, Mexico’s lost Archipelago of the North was seemingly still Mexican. [9]

|

Drawing inspiration from the November 1969-June 1971 occupation of Alcatraz Island by American Indian activists which attracted massive attention to the problems American Indians faced in U.S. society, the Brown Berets hoped their occupation of Catalina Island - code-named "Project Tecolote" (owl) - could raise similar awareness about the discrimination Mexican Americans experienced. As Sánchez stated, the Berets wished to “illustrate the desperate need for a plan for people of Mexican and Indian descent who need a place to live and to be free.” [11]

|

The Mexican Position on its lost Channel Islands

|

When the Brown Berets planned “Project Tecolote,” they were unaware that the Mexican government had already accepted losing the archipelago. In 1944 – fifty years after Esteban Cházari and other intellectuals first presented the Mexican government with a historical study affirming the Channel Islands’ Mexican ownership – President Manuel Ávila Camacho formed a commission to study Mexican claims on the archipelago. The Ávila Camacho Commission concluded in December 1947 that “Mexico lacks rights over the Archipelago of the North.”Rather than draw negative publicity to its inability to reclaim the lost islands, the Mexican government quietly dismissed the issue. [13] Consequently in 1972 it refrained from commenting on the Berets’ Catalina Island invasion.

|

Invading Santa Catalina Island

After months of planning, the Santa Catalina Island invasion began on Wednesday, August 30, 1972. To avoid suspicion, small groups of Brown Berets arrived on Catalina by ferry boat and blended into the tourist crowd in Avalon. On the morning of August 30th the entire group met in a room at the Waikiki Hotel to finalize the occupation. By 8:30am the Berets rented a jeep and transported the group’s supplies to a hillside they named Campo Tecolote. The brush and cactus-covered campsite was adjacent to two of Catalina’s most famous landmarks – Chimes Tower and Catalina Casino.

The sight of the Mexican flag and the Brown Berets’ military formation frightened Avalonians into believing the Mexican Army was invading the island. In reality the Berets were mostly Californian Chicanos, but were also from Arizona, Texas, Colorado, New Mexico, and as far away as Detroit. Although other women participated in the occupation for shorter lengths of time, María Blanco Vega was the only Chicana Brown Beret who stayed for the occupation’s full duration. María married fellow Brown Beret Jerónimo Blanco two days before the occupation began – their stay at Campo Tecolote was their honeymoon. [18]

Accompanied by the Santa Catalina Island Company’s security guards, L.A. County Sheriff Deputies ordered the Berets to leave. Sánchez handed them a 16-page press release explaining the historical context of Article V of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo as well as “the true plight of the Chicano.” [20] Surprised, the deputies left and returned bringing fried chicken and cold drinks. Hoping to avoid scaring tourists away, Avalon Mayor Raymond Rydell and the Island Company allowed the Berets to stay “as long as they want to.”

The generosity was entirely a publicity stunt. In the next day’s Catalina Islander newspaper, Mayor Rydell wrote “it was felt that the Brown Berets would be made to appear rather ridiculous by a friendly reception.” Besides, “a mass arrest would have had a very poor effect upon the Labor Day weekend.” [21]

The generosity was entirely a publicity stunt. In the next day’s Catalina Islander newspaper, Mayor Rydell wrote “it was felt that the Brown Berets would be made to appear rather ridiculous by a friendly reception.” Besides, “a mass arrest would have had a very poor effect upon the Labor Day weekend.” [21]

|

Once it was understood the Brown Berets were not the Mexican Army, the local press joked Campo Tecolote was Catalina’s newest “tourist attraction.” Tour buses drove up to Campo Tecolote on Chimes Road while other Avalonians hiked up to see the Brown Berets for themselves as the occupation attracted national attention. [23] Sánchez explained that the Brown Berets had no demands and did not seek the Channel Islands’ return to Mexico, but hoped to start a discussion about Mexican American social problems.

|

|

When the fright of a Mexican military invasion dissipated, newspapers like the Los Angeles Times relegated the Berets’ invasion to their community pages. CBS Evening News anchor Walter Cronkite held back a grin as he skeptically explained the Berets’ arguments about the Treaty Guadalupe Hidalgo and the Channel Islands. “Everybody at least so far seems to be taking the invasion quite peacefully.” [25]

|

Although the invasion is now remembered with a bit of humor, many island residents were hostile to the Brown Berets’ presence. As the invasion dragged on, the Santa Catalina Island Company blocked access to the campsite and shut off the faucet that supplied Campo Tecolote’s water. Two islanders – an Anglo and a Mexican American – attempted to remove Campo Tecolote’s Mexican flag, but were instead cut up by the hill’s cacti. [27] Others placed large U.S. flags on a hill opposite Campo Tecolote and aggressively demanded that the Chicanos be removed. A mob of them marched onto the camp but were turned away by the Island Company’s security guards.

Mayor Ray Rydell dismissed the Brown Berets’ grievances about anti-Mexican racism in the U.S. saying the “discrimination and inequities they talk about are virtually unknown in Avalon” which he described as a “model community.” Rydell warned residents “Don’t let these racist Brown Berets confuse you.” Even though Mexican people in Avalon had long been discriminated against in public accommodations (such as the Catalina Island Casino), Rydell asserted the Mexican residents of Catalina “are Americans, not Mexican Americans. In this real democratic community of Avalon there are no hyphenated Americans.” In the comfortable world of people like Rydell, the problem isn’t really systemic racism or politicians’ and the media’s relative indifference towards it – instead the real problem is the inconvenience caused by public protest. [27]

Mayor Ray Rydell dismissed the Brown Berets’ grievances about anti-Mexican racism in the U.S. saying the “discrimination and inequities they talk about are virtually unknown in Avalon” which he described as a “model community.” Rydell warned residents “Don’t let these racist Brown Berets confuse you.” Even though Mexican people in Avalon had long been discriminated against in public accommodations (such as the Catalina Island Casino), Rydell asserted the Mexican residents of Catalina “are Americans, not Mexican Americans. In this real democratic community of Avalon there are no hyphenated Americans.” In the comfortable world of people like Rydell, the problem isn’t really systemic racism or politicians’ and the media’s relative indifference towards it – instead the real problem is the inconvenience caused by public protest. [27]

Despite the tensions, the occupation’s overall peaceful nature allowed for some of the Berets to swim on the beach as well as attend mass at St. Catherine’s Catholic Church. The sizable Mexican American community on Avalon had varying opinions on the occupation, but many resident of Barrio Tremont took food and water to the Brown Berets (the group soon depended on these food donations to survive). The Island Company took advantage of the fact that most of the Brown Berets’ allies worked for the company and prevented them from providing further support. “We wanted to help you,” one Mexican American woman told the Berets “but they didn’t let us.” [28]

Prevented from parading in Avalon on September 16th, the Brown Berets commemorated Mexican Independence Day with a proclamation stating the Channel Islands were “sacred lands.” [30] Such acts encouraged the Berets to maintain their spirits, but hunger, strong cold ocean winds, and fatigue wore them out.

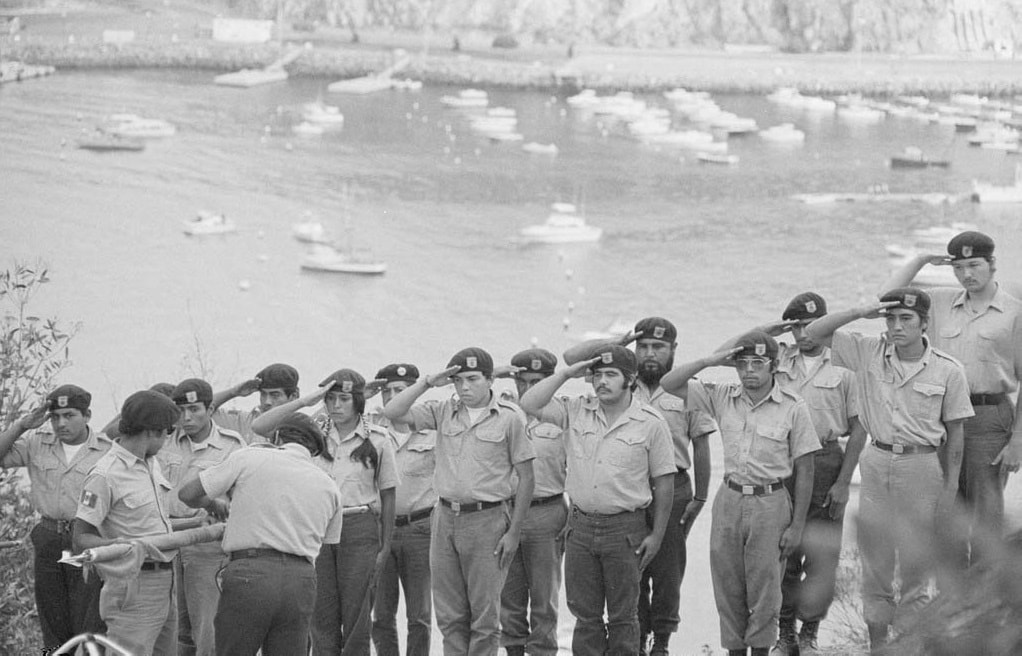

No Island Country for Chicanos

The Brown Berets’ island occupation ended on September 22.Escorted by 40 L.A. sheriff deputies armed in riot gear, Municipal Judge William Osbornevisited Campo Tecolote and informed the group their camp violated Avalon camping ordinances and had to leave or be arrested. [32] The exhausted Brown Berets quickly saluted the Mexican flag in military fashion, broke camp, and made their way to the U.S.S. Avalonwhich ferried them to Los Angeles. Amid their quick evacuation, Sanchez and his group left behind at least two people who were buying groceries before the authorities arrived. [33]

Although he told the press the Berets would return to reoccupy Catalina, the lack of coordination between different parts of the Brown Beret organization was clear when Sánchez questioned why mainland chapters failed to support the contingent on the island. Amid the arguing, numerous accusations of misconduct were raised against Sánchez, leading to his resignation on November 1, 1972. The larger Brown Beret organization dissolved shortly afterwards. In 1978 the U.S.-Mexico Treaty on Maritime Boundaries clarified that their land border extended into the ocean, thus unambiguously reaffirming U.S. control over the Channel Islands. [34]

Although he told the press the Berets would return to reoccupy Catalina, the lack of coordination between different parts of the Brown Beret organization was clear when Sánchez questioned why mainland chapters failed to support the contingent on the island. Amid the arguing, numerous accusations of misconduct were raised against Sánchez, leading to his resignation on November 1, 1972. The larger Brown Beret organization dissolved shortly afterwards. In 1978 the U.S.-Mexico Treaty on Maritime Boundaries clarified that their land border extended into the ocean, thus unambiguously reaffirming U.S. control over the Channel Islands. [34]

Conclusion

The 24-day occupation of Santa Catalina Island by the Brown Berets is a little-remembered event from the end of the Chicano Movement which embodies the lingering effects of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo’s redrawn U.S.-Mexican border. In retrospect, the invasion was as much undertaken to bring attention to anti-Mexican discrimination as it was to try to bring the different Brown Beret factions together to fight for Chicano civil rights.

Although unsuccessful in strengthening Mexico’s claim to the Channel Islands or in ending anti-Mexican discrimination in the U.S., the 1972 Brown Beret occupation at Campo Tecolote highlights Chicano activists’ attempts to correct racial injustices. By invading Santa Catalina Island the Brown Berets demonstrated the ongoing historical relevancy of the U.S.-Mexican border, even in Mexico’s lost archipelago.

Although unsuccessful in strengthening Mexico’s claim to the Channel Islands or in ending anti-Mexican discrimination in the U.S., the 1972 Brown Beret occupation at Campo Tecolote highlights Chicano activists’ attempts to correct racial injustices. By invading Santa Catalina Island the Brown Berets demonstrated the ongoing historical relevancy of the U.S.-Mexican border, even in Mexico’s lost archipelago.

NOTES:

[1] Screenshot from David Sánchez, “Brown Berets History Part 2” (upload of the 1996 film The Brown Berets return to Catalina Island), YouTube, (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zczb_t0O_bk).

[2] David Sánchez, Expedition Through Aztlán(La Puente, CA: Perspective Publications, 1978), 180-181; Dial Torgerson, “Santa Catalina a Bit Up-tight over ‘Invasion,’” Los Angeles Times(Aug. 31, 1972), A-1.

[3] Spanish explorer Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo first visited the island on October 7, 1542, naming it San Salvador. On November 23, 1602, Sebastián Vizcaíno, also in the service of Spain, arrived on the island on the feast day of St. Catherine, renaming it Isla Santa Catalina. Frederic Caire Chiles, California’s Channel Islands: A History(Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2015), 215-218.

[4] Dial Torgerson, “Avalon 'Invaders' Now Just Tourist Attraction,” Los Angeles Times(Sept. 1, 1972), B-1.

[5] Images from Oppression Monitor Daily(http://oppressionmonitor.us/tag/brown-berets/).

[6] Profile picture from Brown Berets Odessa, Twitter(https://twitter.com/brownberets432).

[7] Los Angeles Times Photographic Archives, UCLA Library Special Collections(https://calisphere.org/item/ark:/21198/zz0002w69c/)

[8] Sánchez, Expedition through Aztlán, 174-175.

[9] “Transcript of Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848),” OurDocuments.gov(https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=26&page=transcript).

[10] Photo by Patricia Borjon-Lopez cited in Jessica Wolf, “Exhibition of La Raza photos documents Chicano life in L.A. during the 60s and 70s,” UCLA Newsroom(Dec. 22, 2017), (http://newsroom.ucla.edu/stories/exhibition-of-la-raza-photos-documents-chicano-life-in-l-a-during-the-60s-and-70s).

[11] Sánchez, Expedition through Aztlán, 181-182; Ernesto Chávez, “¡Mi Raza Primero!”: Nationalism, Identity, and Insurgency in the Chicano Movement in Los Angeles, 1966-1978 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 56.

[12] Image from “Manuel Ávila Camacho,” World War II Database (https://ww2db.com/person_bio.php?person_id=226).

[13] Jorge A. Vargas, El Archipiélago del Norte: ¿Territorio de México o de los Estados Unidos?(México, DF: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1993), 8-9, 154-155.

[14] Sánchez, Expedition through Aztlán, 179-180.

[15] Screenshot from The Brown Berets return to Catalina Island(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zczb_t0O_bk).

[16] Screenshot from The Brown Berets return to Catalina Island(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zczb_t0O_bk).

[17] Photo by Kent Henderson, Long Beach Press Telegram(Aug. 31, 1972), pg. 1.

[18] Dial Torgerson, “Avalon 'Invaders' Now Just Tourist Attraction,” Los Angeles Times(Sept.. 1, 1972), B-1. The women in the group included Maria Vega of Las Cruces, New Mexico, who accompanied her husband Jeronimo Blanco from the invasion’s beginning to end. According to David Sánchez, Pauline Mendoza joined the group later. Reports on the Brown Berets invasion often only mention Maria Blanco’s presence. Sánchez, Expedition through Aztlán, 184.

[19] Screenshot from The Brown Berets return to Catalina Island(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zczb_t0O_bk).

[20] Sánchez, Expedition through Aztlán, 180.

[21] Mayor Rydell was a retiree familiar with handling young militants from his time as Vice-Chancellor of the California State College system. Dial Torgerson, “Santa Catalina a Bit Up-tight over ‘Invasion,’” Los Angeles Times(Aug. 31, 1972), A-1; Catalina Islander (Aug. 31, 1972) remarks quoted in Marcelino Saucedo, Dream Makers and Dream Catchers: The Story of the Mexican Heritage on Catalina Island (Virginia Beach, VA: Donning Co. Publishers, 2008), 125-126.

[22] Screenshot from The Brown Berets return to Catalina Island(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zczb_t0O_bk).

[23] Dial Torgerson, “Avalon 'Invaders' Now Just Tourist Attraction,” Los Angeles Times(Sept. 1, 1972), B-1.

[24] Photo by Maria Marquez Sanchez in Carren Jao and Michael Naeimollah, “Narrated Photo Essay: Maria Marquez Sanchez on the Two Sides of Her Activism,” KCET(https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/narrated-photo-essay-maria-marquez-sanchez-on-the-two-sides-of-her-activism); Screenshot from The Brown Berets return to Catalina Island(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zczb_t0O_bk).

[25] Randy Ontiveros, “No Golden Age: Television News and the Chicano Civil Rights Movement,” American QuarterlyVol. 62, No. 4 (Dec. 2010), 897-898; Al Martinez, “Judge Asks Berets to Leave – They Do,” Los Angeles Times(Sept. 23, 1972), B-1.

[26] Screenshot from The Brown Berets return to Catalina Island(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zczb_t0O_bk).

[27] Sánchez, Expedition through Aztlán, 182-183; “The Southland: Catalina ‘Invaders’ Blockaded,” Los Angeles Times (Sept. 11, 1972), A-2; Catalina Islander (Aug. 31, 1972) remarks quoted in Marcelino Saucedo, Dream Makers and Dream Catchers: The Story of the Mexican Heritage on Catalina Island (Virginia Beach, VA: Donning Co. Publishers, 2008), 125-126.

[28] Sánchez, Expedition through Aztlán, 182-184.

[29] Photo by Maria Marquez Sanchez in “Narrated Photo Essay: Maria Marquez Sanchez,” KCET(https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/narrated-photo-essay-maria-marquez-sanchez-on-the-two-sides-of-her-activism).

[30] Sánchez, Expedition through Aztlán, 185; “’El Grito’ Festivities: Parade Highlights Mexican Celebration of Independence,” Los Angeles Times(Sept. 17, 1972), A-3.

[31] Photo by Maria Marquez Sanchez in “Narrated Photo Essay: Maria Marquez Sanchez,” KCET(https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/narrated-photo-essay-maria-marquez-sanchez-on-the-two-sides-of-her-activism).

[32] Sánchez, Expedition Through Aztlán, 180-182, 188-190; Al Martinez, “Judge Asks Berets to Leave – They Do,” Los Angeles Times(Sept. 23, 1972), B-1.

[33] Sánchez, Expedition Through Aztlán, 188-189.

[34] Sánchez, Expedition Through Aztlán, 190; Chávez, “¡Mi Raza Primero!,” 56-57. The 1978 U.S.-Mexico Treaty on Maritime Boundaries outlined the two countries sea borders, preventing them from making claims on opposite sides of the maritime border. Vargas, El Archipiélago del Norte, 154-155.

[35] Screenshot from The Brown Berets return to Catalina Island(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zczb_t0O_bk)

[2] David Sánchez, Expedition Through Aztlán(La Puente, CA: Perspective Publications, 1978), 180-181; Dial Torgerson, “Santa Catalina a Bit Up-tight over ‘Invasion,’” Los Angeles Times(Aug. 31, 1972), A-1.

[3] Spanish explorer Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo first visited the island on October 7, 1542, naming it San Salvador. On November 23, 1602, Sebastián Vizcaíno, also in the service of Spain, arrived on the island on the feast day of St. Catherine, renaming it Isla Santa Catalina. Frederic Caire Chiles, California’s Channel Islands: A History(Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2015), 215-218.

[4] Dial Torgerson, “Avalon 'Invaders' Now Just Tourist Attraction,” Los Angeles Times(Sept. 1, 1972), B-1.

[5] Images from Oppression Monitor Daily(http://oppressionmonitor.us/tag/brown-berets/).

[6] Profile picture from Brown Berets Odessa, Twitter(https://twitter.com/brownberets432).

[7] Los Angeles Times Photographic Archives, UCLA Library Special Collections(https://calisphere.org/item/ark:/21198/zz0002w69c/)

[8] Sánchez, Expedition through Aztlán, 174-175.

[9] “Transcript of Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848),” OurDocuments.gov(https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=26&page=transcript).

[10] Photo by Patricia Borjon-Lopez cited in Jessica Wolf, “Exhibition of La Raza photos documents Chicano life in L.A. during the 60s and 70s,” UCLA Newsroom(Dec. 22, 2017), (http://newsroom.ucla.edu/stories/exhibition-of-la-raza-photos-documents-chicano-life-in-l-a-during-the-60s-and-70s).

[11] Sánchez, Expedition through Aztlán, 181-182; Ernesto Chávez, “¡Mi Raza Primero!”: Nationalism, Identity, and Insurgency in the Chicano Movement in Los Angeles, 1966-1978 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 56.

[12] Image from “Manuel Ávila Camacho,” World War II Database (https://ww2db.com/person_bio.php?person_id=226).

[13] Jorge A. Vargas, El Archipiélago del Norte: ¿Territorio de México o de los Estados Unidos?(México, DF: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1993), 8-9, 154-155.

[14] Sánchez, Expedition through Aztlán, 179-180.

[15] Screenshot from The Brown Berets return to Catalina Island(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zczb_t0O_bk).

[16] Screenshot from The Brown Berets return to Catalina Island(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zczb_t0O_bk).

[17] Photo by Kent Henderson, Long Beach Press Telegram(Aug. 31, 1972), pg. 1.

[18] Dial Torgerson, “Avalon 'Invaders' Now Just Tourist Attraction,” Los Angeles Times(Sept.. 1, 1972), B-1. The women in the group included Maria Vega of Las Cruces, New Mexico, who accompanied her husband Jeronimo Blanco from the invasion’s beginning to end. According to David Sánchez, Pauline Mendoza joined the group later. Reports on the Brown Berets invasion often only mention Maria Blanco’s presence. Sánchez, Expedition through Aztlán, 184.

[19] Screenshot from The Brown Berets return to Catalina Island(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zczb_t0O_bk).

[20] Sánchez, Expedition through Aztlán, 180.

[21] Mayor Rydell was a retiree familiar with handling young militants from his time as Vice-Chancellor of the California State College system. Dial Torgerson, “Santa Catalina a Bit Up-tight over ‘Invasion,’” Los Angeles Times(Aug. 31, 1972), A-1; Catalina Islander (Aug. 31, 1972) remarks quoted in Marcelino Saucedo, Dream Makers and Dream Catchers: The Story of the Mexican Heritage on Catalina Island (Virginia Beach, VA: Donning Co. Publishers, 2008), 125-126.

[22] Screenshot from The Brown Berets return to Catalina Island(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zczb_t0O_bk).

[23] Dial Torgerson, “Avalon 'Invaders' Now Just Tourist Attraction,” Los Angeles Times(Sept. 1, 1972), B-1.

[24] Photo by Maria Marquez Sanchez in Carren Jao and Michael Naeimollah, “Narrated Photo Essay: Maria Marquez Sanchez on the Two Sides of Her Activism,” KCET(https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/narrated-photo-essay-maria-marquez-sanchez-on-the-two-sides-of-her-activism); Screenshot from The Brown Berets return to Catalina Island(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zczb_t0O_bk).

[25] Randy Ontiveros, “No Golden Age: Television News and the Chicano Civil Rights Movement,” American QuarterlyVol. 62, No. 4 (Dec. 2010), 897-898; Al Martinez, “Judge Asks Berets to Leave – They Do,” Los Angeles Times(Sept. 23, 1972), B-1.

[26] Screenshot from The Brown Berets return to Catalina Island(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zczb_t0O_bk).

[27] Sánchez, Expedition through Aztlán, 182-183; “The Southland: Catalina ‘Invaders’ Blockaded,” Los Angeles Times (Sept. 11, 1972), A-2; Catalina Islander (Aug. 31, 1972) remarks quoted in Marcelino Saucedo, Dream Makers and Dream Catchers: The Story of the Mexican Heritage on Catalina Island (Virginia Beach, VA: Donning Co. Publishers, 2008), 125-126.

[28] Sánchez, Expedition through Aztlán, 182-184.

[29] Photo by Maria Marquez Sanchez in “Narrated Photo Essay: Maria Marquez Sanchez,” KCET(https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/narrated-photo-essay-maria-marquez-sanchez-on-the-two-sides-of-her-activism).

[30] Sánchez, Expedition through Aztlán, 185; “’El Grito’ Festivities: Parade Highlights Mexican Celebration of Independence,” Los Angeles Times(Sept. 17, 1972), A-3.

[31] Photo by Maria Marquez Sanchez in “Narrated Photo Essay: Maria Marquez Sanchez,” KCET(https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/narrated-photo-essay-maria-marquez-sanchez-on-the-two-sides-of-her-activism).

[32] Sánchez, Expedition Through Aztlán, 180-182, 188-190; Al Martinez, “Judge Asks Berets to Leave – They Do,” Los Angeles Times(Sept. 23, 1972), B-1.

[33] Sánchez, Expedition Through Aztlán, 188-189.

[34] Sánchez, Expedition Through Aztlán, 190; Chávez, “¡Mi Raza Primero!,” 56-57. The 1978 U.S.-Mexico Treaty on Maritime Boundaries outlined the two countries sea borders, preventing them from making claims on opposite sides of the maritime border. Vargas, El Archipiélago del Norte, 154-155.

[35] Screenshot from The Brown Berets return to Catalina Island(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zczb_t0O_bk)