Santa Catalina Island: Borderland at Sea

Text and original photography by Carlos Francisco Parra

April 18, 2020

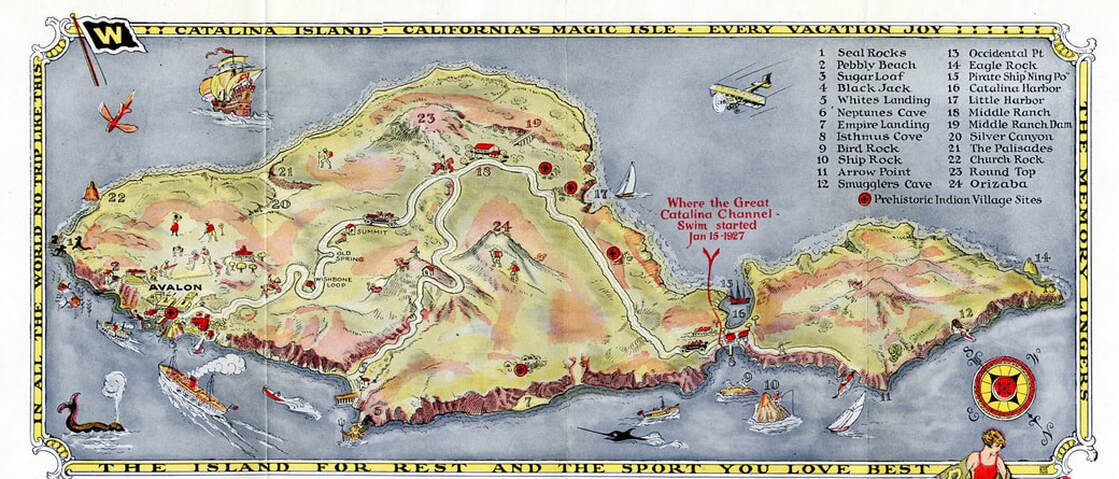

Located just 23 miles (37km) from the Port of Los Angeles, Santa Catalina Island is the most visited and familiar of all the Channel Islands in Mexico’s lost Archipelago of the North. With over 1,021,177 visitors during 2019, Catalina is often promoted to tourists as “California’s magic isle” due to its resorts and history with the rich and famous [1]. Beyond the glamour, though, Catalina’s past demonstrates the island’s role as a borderland at sea between indigenous, Mexican, and U.S. cultures. The real magic of Catalina Island is in its deeply-rooted cultural history as a maritime borderland along the larger U.S.-Mexican border region.

Quick Summary:

- Indigenous Tongva people occupied Santa Catalina Island (Pimu) for nearly 7,000 years prior to European contact

- During the 1820s the Catalina Island Tongva relocated to Mexican-era Los Angeles where they were baptized and founded the Ranchería de los Pipimares (Pipimares village)

- Mexican immigrants moved to Catalina Island to work in ranching, tourism, and other economic activities developed by White American investors

- Catalina Island Mexican American community, centered along the Tremont Street neighborhood, experienced different levels of discrimination during the twentieth century

The Early Borderlands of Catalina/Pimu Island

The history of Catalina Island follows patterns of interracial interaction seen throughout the U.S.-Mexico borderlands between indigenous people, Mexicans, and White Americans. Long before tourists became enchanted with Catalina, the island (as well as nearby San Clemente and San Nicolás islands) was the home of a branch of the indigenous Tongva (or Gabrielino) peoples of the greater Los Angeles area. The Tongvas’ name for Catalina was Pimu or Pimugna. [2] Archaeological research indicates the Tongvas lived on Pimu/Catalina since about 5,000 B.C.

As with their Clementeño and Nicoleño neighbors, the Pimu Tongvas crafted strong canoes – called ti’ats – out of redwood logs which ocean currents occasionally washed onshore after flooding in Northern California. Ti’ats could carry 3-30 people. Paddling on ti’ats the Tongva traded with the mainland, the Clementeños and the people of San Nicolás Island via Santa Bárbara Island. [3]

As with their Clementeño and Nicoleño neighbors, the Pimu Tongvas crafted strong canoes – called ti’ats – out of redwood logs which ocean currents occasionally washed onshore after flooding in Northern California. Ti’ats could carry 3-30 people. Paddling on ti’ats the Tongva traded with the mainland, the Clementeños and the people of San Nicolás Island via Santa Bárbara Island. [3]

Ti’at boats were an essential part of the Pimu Tongva life, but like many aspects of island and mainland Tongva culture the ti’at-building tradition ended during the Spanish/Mexican/U.S. colonization of California. In the 1990s members of the Tongva, Chumash, and Acjachemen communities formed the Ti’at Society to revive this indigenous seafaring tradition by launching the first ti’at in nearly 150 years, the Moomat ahiko, or “breath of the ocean.” [4]

|

Although water sources on the island were limited, the Pimu Tongva population numbered between 500-2,500 people, living in villages throughout Catalina such as at Little Harbor and Avalon. The ocean’s bounty of fish and abalone shellfish were dietary staples along with island acorns. [6] Untrained amateur archaeologists working in the archipelago in the late 1800s/early 1900s have complicated research on Pimu Tongva history by poorly documenting excavations, disturbing former village sites, looting graves, and scattering/destroying human remains. [7]

|

Pimu Tongva contact with European explorers began in 1542 when the expedition of Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo (who may have died on Catalina) visited. The 1602 Sebastián Vizcaíno expedition gave Isla Santa Catalina its current name. While the Spanish colonization of Alta California would not begin until 1769, the Cabrillo and Vizcaíno expeditions (as well as visiting Spanish ships returning to Mexico from the Spanish Philippines on the Manila Galleon Trade Route) may have introduced deadly viruses among the Tongva islanders. [9]

|

Following the pattern of the other Channel Islands’ depopulation during the colonization of California, by the 1820s the remaining Pimu Tongva relocated to the mainland, leaving Catalina uninhabited for the first time in nearly 7,000 years. After the Tongva left Catalina, smugglers and sea otter hunters (who pushed the species to the brink of extinction) occasionally visited the abandoned island. Using church records, anthropologists have determined that many of the Pimu Tongva relocated to the Los Angeles area where they became laborers or servants for different Mexican families who called them (as well as the Nicoleño and Clementeño islanders) Pipimares. [10] The Pimu/Catalina Island Tongva became Pipimares upon crossing the cultural border between indigenous island life and their new reality as baptized laborers living in Mexican-era Alta California.

|

Beginning in the 1820s many Pimu Tongva and other native islanders founded their own village – known in Mexican records as the Ranchería de los Pipimares – 1.5 miles south of the historic Los Angeles Plaza and La Placita Church where many of them were baptized by Mexican godparents. The Ranchería de los Pipimares was across from the property of José Jacinto Reyes, a frequent godfather of indigenous islanders according to records from the La Placita Church. Anthropologists believe the islanders moved to live near Reyes because he may have employed them as his servants. The Ranchería de los Pipimares was located on the west side of San Pedro Street between 7th and 8th Streets in what is now Downtown Los Angeles. [11]

|

Anthropologists have identified the corner of San Pedro and 7th Streets as the heart of the Pipimares Ranchería. In an oral history interview Cesaría Valenzuela recalled that as a young girl in 1842 she and her family saw the Pipimares celebrate a multi-day mourning ritual in which the Pipimares danced around a large bonfire into which they threw chia seeds, berries, pine nuts, and possessions owned by the deceased individual. Cesaría’s description matches accounts of similar mourning rituals by mainland Tongva people.

|

The Pimu Tongva remained at the Ranchería de los Pipimares until 1846 when the Los Angeles town council, responding to requests from nearby landowners, forced the islanders to move to a different Native American village east of the Los Angeles River. That site was also destroyed by the town the next year to appease land-hungry townspeople. Over time the Catalina Island Tongva and other Pipimares absorbed into the mainland Tongva community of current-day Southern California. Despite the Tongvas’ legacy across the coasts and islands of California, most people are unfamiliar with them. [13]

Little development of Santa Catalina Island took place during Mexican-era Alta California, but the July 1846 decision by Governor Pío de Jesús Pico to award the abandoned island as a private land grant profoundly changed its future. Pico awarded the entire island to Thomas Robbins, a long-time resident of Alta California and naturalized Mexican citizen. Popular myth asserts Pico sold Catalina to Robbins in exchange for a white horse and silver saddle to escape approaching U.S. troops at the start of the U.S.-Mexican War, however there is no proof for this. [14]

Little development of Santa Catalina Island took place during Mexican-era Alta California, but the July 1846 decision by Governor Pío de Jesús Pico to award the abandoned island as a private land grant profoundly changed its future. Pico awarded the entire island to Thomas Robbins, a long-time resident of Alta California and naturalized Mexican citizen. Popular myth asserts Pico sold Catalina to Robbins in exchange for a white horse and silver saddle to escape approaching U.S. troops at the start of the U.S.-Mexican War, however there is no proof for this. [14]

Putting Catalina on the Map

|

For most people Catalina’s tourism history – rather than its history as a multiracial maritime borderland – comes to mind because of the efforts of the island’s owners to make it into a vacation paradise. The Santa Catalina Island Company (first formed in 1894 after the island changed hands multiple times) struggled to develop Catalina as a tourist destination until chewing gum tycoon William Wrigley, Jr., vacationed there with his wife in 1919. Falling in love with the island, Wrigley purchased the company (thus buying the island itself). Wrigley invested large amounts of money making Catalina and its town of Avalon one of Southern California’s premiere tourist attractions. [17]

The Santa Catalina Island Company still operates much of the island’s tourist businesses, but since 1975 the Catalina Island Conservancy – an entity created by the Wrigley family – controls almost 90% of the island’s land area. The Conservancy works to protect the natural heritage of the most accessible island in Mexico’s lost Archipelago of the North. [18] |

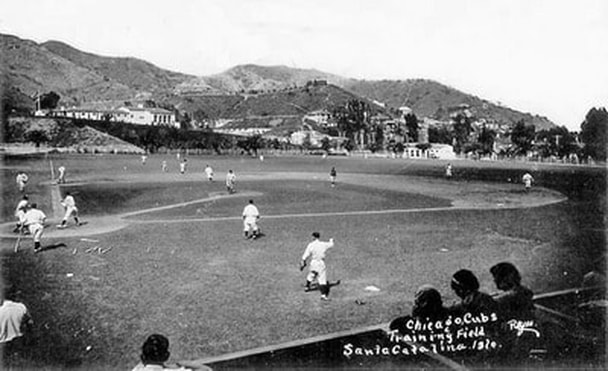

Besides owning Wrigley’s Chewing Gum Company and the Santa Catalina Island Company, William Wrigley, Jr., also owned the Chicago Cubs. From 1921-1952, the Cubs’ spring training was held on Catalina. As Marcelino Saucedo notes in his book Dream Makers and Dream Catchers, many Mexican American boys living in Avalon daydreamed of becoming Cubs at they watched them train. [19]

Mexican American Barrios and Borderlands on Isla Santa Catalina

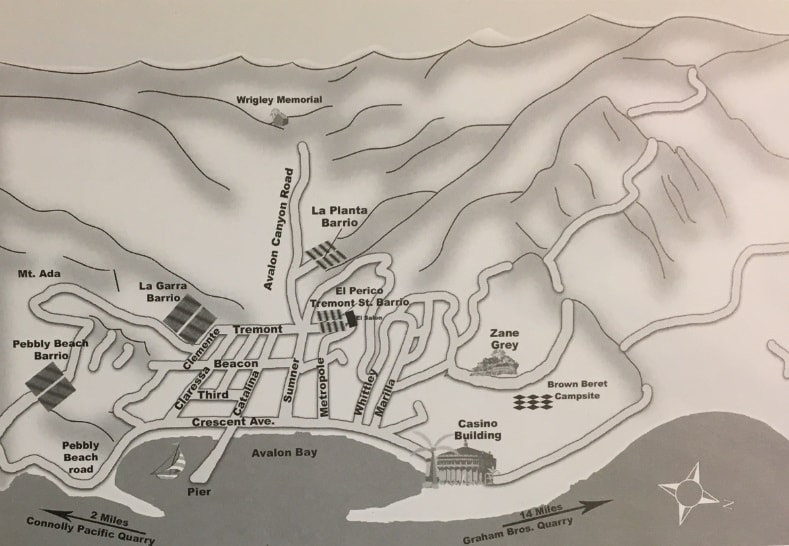

Catalina’s economic development brought many Mexican immigrant and Mexican American workers to the island. Many worked in ranches or the Pebbly Beach rock quarry, but mostly lived around Avalon (the archipelago’s only incorporated city). According to author Marcelino Saucedo four different Mexican barrios (or neighborhoods) emerged on the island starting in the 1900s. Barrio Pebbly Beach, located southeast of Avalon, was built for laborers working in the Connolly Pacific Quarry. Among the barrio’s houses was the Salon de Brisa, an open-air platform for social gatherings. Just outside of Avalon along Wrigley Terrace was the Barrio La Garra, named as such because of the many “clothes flapping in the breeze.” Inside Avalon Canyon, the Barrio La Planta had about twelve wooden houses for Mexican workers and their families.

|

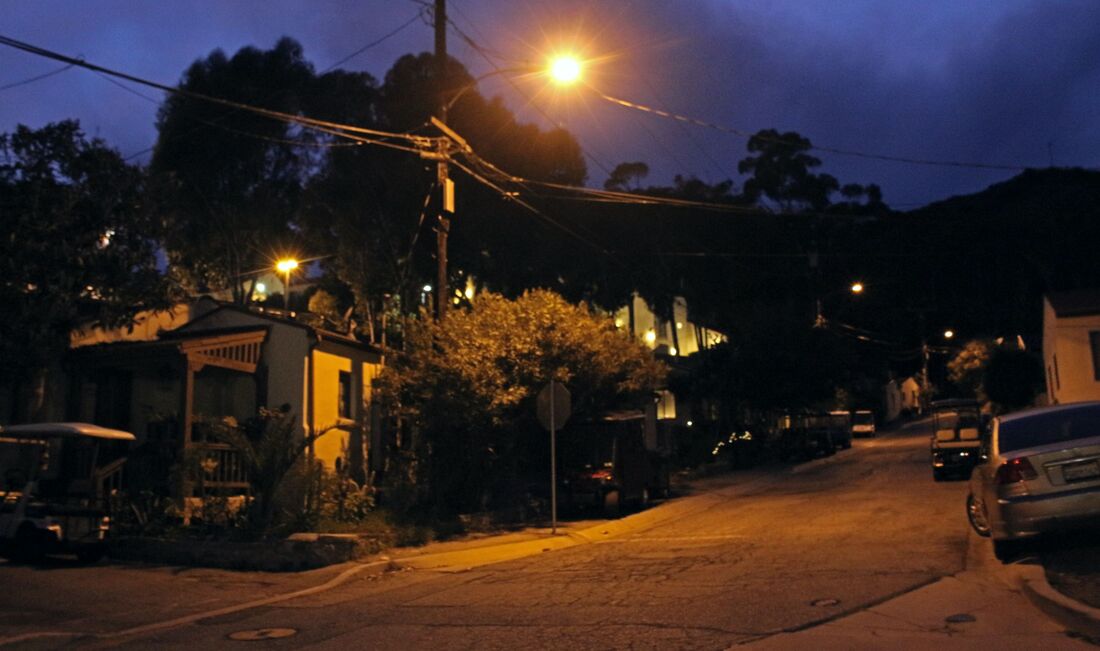

Barrio Tremont, the most significant of the barrios, is located along Avalon’s interior along Tremont Street and initially called “El Perico” (the Parrot). In 1927-1928 Barrio Tremont’s shacks were demolished on William Wrigley’s orders and rebuilt to better accommodate Catalina’s Mexican residents and beautify the island. Most of the Barrio Tremont homes built in the late twenties still stand. In time residents of the other neighborhoods moved into Barrio Tremont’s expanded housing facilities, making it Catalina’s main Mexican neighborhood. [21]

|

|

During the Tremont Street redevelopment project the Santa Catalina Island Company built Tremont Hall for neighborhood residents. According to William Wrigley, Jr., “Dances, banquets, and Spanish plays held by the Mexicans in this beautifully equipped hall can probably not be duplicated anywhere else outside of Latin land. To keep people happy, they should be placed in an environment to which they are accustomed and provision made for recreation according to their customs.” However, Barrio Tremont residents who faced anti-Mexican discrimination understood the hall as having been built to discourage them from going to the Catalina Island Casino which did not admit Mexicans. A Mexican band composed of Barrio Tremont residents (left) gathers outside of Tremont Hall in the early 1930s. [22]

|

Besides not being allowed inside the Catalina Island Casino, Mexican people in Catalina had daily reminders that the island had long since stopped being Mexican territory. Oral histories recount the discrimination they faced throughout the 1900s, including being banned from popular beaches. According to Saucedo, many Mexicans “did not feel comfortable speaking Spanish” outside of Barrio Tremont. Pastor López remembered “I was told time and again to go back to Mexico if I wanted to speak Spanish.” Another Mexican Avalonian remembered “I used to get kicked off the public benches – a guy would go around telling us not to sit on the benches because they were for tourists.” [23]

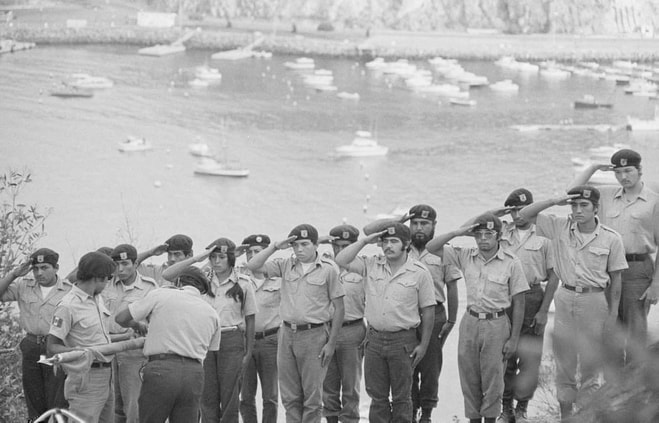

Many Barrio Tremont Mexicans remembered their brushes with discrimination when they donated food to the Chicano Brown Berets during their occupation of the island from August 30-Sept 22, 1972. The Brown Berets’ occupation, justifying itself on the claim that Catalina and the rest of the Channel Islands were still Mexican soil (according to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo), was undertaken specifically to protest against anti-Mexican racism and police brutality. The Berets’ civil rights protest in the lost Mexican archipelago took place on a hillside camp they named Campo Tecolote.

(Read more about the Brown Beret invasion of Catalina Island here)

Many Barrio Tremont Mexicans remembered their brushes with discrimination when they donated food to the Chicano Brown Berets during their occupation of the island from August 30-Sept 22, 1972. The Brown Berets’ occupation, justifying itself on the claim that Catalina and the rest of the Channel Islands were still Mexican soil (according to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo), was undertaken specifically to protest against anti-Mexican racism and police brutality. The Berets’ civil rights protest in the lost Mexican archipelago took place on a hillside camp they named Campo Tecolote.

(Read more about the Brown Beret invasion of Catalina Island here)

The Brown Berets’ Campo Tecolote campsite (pictured above in 1972) was located in the cliff-side grove next to the Catalina Island Casino. [24]

Overlooking Avalon Bay and the famous Casino which used to prohibit Mexicans, the Berets raised a giant Mexican flag for all to see. Support from allies in Barrio Tremont kept the Berets going until a municipal judge, escorted by 40 sheriff’s deputies in riot gear, ordered them to leave on September 22, 1972. One Barrio Tremont resident told the Berets they wanted to help more, but Catalina Island Company bosses pressured their Mexican American workers against it. [25]

Barrio Tremont is still a cultural borderland today, with the sound of Spanish pop music and conversations in English, Spanish, and Spanglish filling the air. Looking around the U.S. as a whole, have the Brown Berets’ 1970s grievances against anti-Mexican racism truly been overcome in the years since?

Barrio Tremont is still a cultural borderland today, with the sound of Spanish pop music and conversations in English, Spanish, and Spanglish filling the air. Looking around the U.S. as a whole, have the Brown Berets’ 1970s grievances against anti-Mexican racism truly been overcome in the years since?

Conclusion – A Changing Borderland at Sea

|

While California’s “magic isle” is not often celebrated as a borderland, Santa Catalina Island’s long history demonstrates the larger processes of cultural change, nation-building, and economic development which have occurred throughout the wider U.S.-Mexican border region. The Pimu Tongvas’ experiences with colonization (including their relocation and absorption into Los Angeles society), the island’s economic development by U.S. industrialists, and the often discriminatory experiences of Mexican workers follow a model seen in border areas like Southern Arizona or South Texas [26]. Despite the Brown Berets and others’ efforts, Mexico lost its Channel Islands when the U.S.-Mexican border was drawn in 1848, yet Pimu/Catalina’s history is still a story of crossing boundaries. Whether rowing across the sea on a ti’at, or as a villager in the Ranchería de los Pipimares in 1830s Los Angeles, or as a resident of Barrio Tremont, Catalina’s real magic is its history as a maritime borderland for different cultures.

|

Suggested Reading:

Marcelino Saucedo, Dream Makers and Dream Catchers: The Story of the Mexican Heritage on Catalina Island (Virginia Beach, VA: Donning Co. Publishers, 2008).

NOTES:

[1] “Avalon Passenger Counts by Month, Year and Type 2009-2019,” Catalina Island Chamber of Commerce and Visitors Bureau (2020), (https://www.catalinachamber.com/community-information/catalina-visitor-statistics/); Glen Creason, “CityDig: Catalina Island in 1927: California’s Magic Isle,” Los Angeles Magazine (Feb. 13, 2013), (https://www.lamag.com/citythinkblog/citydig-catalina-island-in-1927-californias-magic-isle/).

[2] Desiree R. Martinez, Wendy G. Teeter, and Karimah Kennedy-Richardson, “Returning the tataayiyam honuuka’ (Ancestors) to the Correct Home: The Importance of Background Investigations for NAGPRA Claims,” Curator: The Museum Journal vol. 57, no. 2 (2014), 201; William McCawley, The First Angelinos: The Gabrielino Indians of Los Angeles (Banning, CA: Malki Museum Press, 1996), 79.

[3] Frederic Caire Chiles, California’s Channel Islands: A History (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2015), 182, 197, 215-216; Paige Bardolph, “Traditional Boat Building Helps Native Community Hone Ecological Knowledge,” KCET (Nov. 5, 2019), (https://www.kcet.org/shows/tending-nature/traditional-boat-building-helps-native-community-hone-ecological-knowledge); “Jerry Lassos,” Island of the Blue Dolphins-National Park Service (https://www.nps.gov/subjects/islandofthebluedolphins/lassos.htm).

[4] Paige Bardolph, “Traditional Boat Building Helps Native Community Hone Ecological Knowledge,” KCET (Nov. 5, 2019), (https://www.kcet.org/shows/tending-nature/traditional-boat-building-helps-native-community-hone-ecological-knowledge).

[5] Desiree R. Martinez, “Cultural Setting,” Report for Metropole Vaults Replacement Project, Southern California Edison, Avalon, Catalina Island (2015), (http://whereareyouquetzalcoatl.com/mesofigurineproject/EthnicAndIndigenousStudiesArticles/MartinezEtAl_2015.pdf).

[6] Caire Chiles, 215-216.

[7] Desiree R. Martinez, Wendy G. Teeter, and Karimah Kennedy-Richardson, “Returning the tataayiyam honuuka’ (Ancestors) to the Correct Home: The Importance of Background Investigations for NAGPRA Claims,” Curator: The Museum Journal, vol. 57, no. 2(April 2014): 199-211. See also Clement Meighan, “The Little Harbor Site, Catalina Island: An Example of Ecological Interpretation in Archaeology,” American Antiquity, vol. 24, no. 4 (1959): 383-405; Desiree R. Martinez, “Cultural Setting,” Report for Metropole Vaults Replacement Project, Southern California Edison, Avalon, Catalina Island (2015), (http://whereareyouquetzalcoatl.com/mesofigurineproject/EthnicAndIndigenousStudiesArticles/MartinezEtAl_2015.pdf).

[8] Glen Creason, “CityDig: Catalina Island in 1927: California’s Magic Isle,” Los Angeles Magazine (Feb. 13, 2013), (https://www.lamag.com/citythinkblog/citydig-catalina-island-in-1927-californias-magic-isle/).

[9] Caire Chiles, 216-217; Jon M. Erlandson and Kevin Bartoy, “Cabrillo, the Chumash, and Old World Diseases,” Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, vol. 17, no. 2 (1995): 153-173.

[10] Susan L. Morris, John R. Johnson, et al., “The Nicoleños in Los Angeles: Documenting the Fate of the Lone Woman’s Community,” Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology vol. 36, no 1 (2016): 97; John R. Johnson and Sally McLendon, “The Social History of Native Islanders Following Missionization,” Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History Conference Paper (2002), 647; Caire Chiles 217.

[11] Susan Morris, John R. Johnson, et al., “The Nicoleños in Los Angeles: Documenting the Fate of the Lone Woman’s Community,” Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, vol. 36, no. 1 (2016): 97-98, 109-110.

[12] Susan Morris, John R. Johnson, et al., “The Nicoleños in Los Angeles,” 97-98.

[13] Susan Morris, John R. Johnson, et al., “The Nicoleños in Los Angeles,” 97-98, 109-110.

[14] Caire Chiles, 218; Martin Cole, “The Granting of Santa Catalina Island,” in Pio Pico Miscellany (Whittier, CA: Governor Pio Pico Mansion Society, 1978), 67. The horse/silver saddle exchange for the island (and its racist innuendos) appears to have been created later by Catalina’s tourism promoters.

[15] 4-5,000 military servicemen occupied Catalina Island after the U.S. entry into World War II and required all civilians to carry identification at all times. Marcelino Saucedo, Dream Makers and Dream Catchers: The Story of the Mexican Heritage on Catalina Island (Virginia Beach, VA: Donning Co. Publishers, 2008), 63.

[16] Esteban Cházari quoted in Jorge A. Vargas, El Archipiélago del Norte: ¿Territorio de México o de los Estados Unidos? (México, DF: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1993), 94.

[17] Caire Chiles, 218-226; Saucedo, 143.

[18] Caire Chiles, 236

[19] Saucedo, 49. The only break in the Cubs’ spring training in Catalina was from 1942-1945 during World War II. Image from Sam Gnerre, “Spring training with the Cubs on Catalina Island” South Bay History (June 24, 2009), (http://blogs.dailybreeze.com/history/2009/06/24/spring-training-with-the-cubs-on-catalina-island).

[20] Saucedo, 7.

[21] Saucedo, 16-19.

[22] William Wrigley, Jr., quoted in Nov. 13, 1929, Catalina Islander article, quoted by Saucedo, 31. See also page 26 and for band photo page 38.

[23] Saucedo, 16-19, Pastor Lopez and Vernon Lopez quoted on pages 26-27.

[24] Photo by Maria Marquez Sanchez in “Narrated Photo Essay: Maria Marquez Sanchez,” KCET (https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/narrated-photo-essay-maria-marquez-sanchez-on-the-two-sides-of-her-activism).

[25] David Sánchez, Expedition Through Aztlán (La Puente, CA: Perspective Publications, 1978), 182-184.

[26] Samuel Truett, Fugitive Landscapes: The Forgotten History of the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008); Omar S. Valerio-Jiménez, River of Hope: Forging Identity and Nation in the Rio Grande Borderlands (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013).

[2] Desiree R. Martinez, Wendy G. Teeter, and Karimah Kennedy-Richardson, “Returning the tataayiyam honuuka’ (Ancestors) to the Correct Home: The Importance of Background Investigations for NAGPRA Claims,” Curator: The Museum Journal vol. 57, no. 2 (2014), 201; William McCawley, The First Angelinos: The Gabrielino Indians of Los Angeles (Banning, CA: Malki Museum Press, 1996), 79.

[3] Frederic Caire Chiles, California’s Channel Islands: A History (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2015), 182, 197, 215-216; Paige Bardolph, “Traditional Boat Building Helps Native Community Hone Ecological Knowledge,” KCET (Nov. 5, 2019), (https://www.kcet.org/shows/tending-nature/traditional-boat-building-helps-native-community-hone-ecological-knowledge); “Jerry Lassos,” Island of the Blue Dolphins-National Park Service (https://www.nps.gov/subjects/islandofthebluedolphins/lassos.htm).

[4] Paige Bardolph, “Traditional Boat Building Helps Native Community Hone Ecological Knowledge,” KCET (Nov. 5, 2019), (https://www.kcet.org/shows/tending-nature/traditional-boat-building-helps-native-community-hone-ecological-knowledge).

[5] Desiree R. Martinez, “Cultural Setting,” Report for Metropole Vaults Replacement Project, Southern California Edison, Avalon, Catalina Island (2015), (http://whereareyouquetzalcoatl.com/mesofigurineproject/EthnicAndIndigenousStudiesArticles/MartinezEtAl_2015.pdf).

[6] Caire Chiles, 215-216.

[7] Desiree R. Martinez, Wendy G. Teeter, and Karimah Kennedy-Richardson, “Returning the tataayiyam honuuka’ (Ancestors) to the Correct Home: The Importance of Background Investigations for NAGPRA Claims,” Curator: The Museum Journal, vol. 57, no. 2(April 2014): 199-211. See also Clement Meighan, “The Little Harbor Site, Catalina Island: An Example of Ecological Interpretation in Archaeology,” American Antiquity, vol. 24, no. 4 (1959): 383-405; Desiree R. Martinez, “Cultural Setting,” Report for Metropole Vaults Replacement Project, Southern California Edison, Avalon, Catalina Island (2015), (http://whereareyouquetzalcoatl.com/mesofigurineproject/EthnicAndIndigenousStudiesArticles/MartinezEtAl_2015.pdf).

[8] Glen Creason, “CityDig: Catalina Island in 1927: California’s Magic Isle,” Los Angeles Magazine (Feb. 13, 2013), (https://www.lamag.com/citythinkblog/citydig-catalina-island-in-1927-californias-magic-isle/).

[9] Caire Chiles, 216-217; Jon M. Erlandson and Kevin Bartoy, “Cabrillo, the Chumash, and Old World Diseases,” Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, vol. 17, no. 2 (1995): 153-173.

[10] Susan L. Morris, John R. Johnson, et al., “The Nicoleños in Los Angeles: Documenting the Fate of the Lone Woman’s Community,” Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology vol. 36, no 1 (2016): 97; John R. Johnson and Sally McLendon, “The Social History of Native Islanders Following Missionization,” Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History Conference Paper (2002), 647; Caire Chiles 217.

[11] Susan Morris, John R. Johnson, et al., “The Nicoleños in Los Angeles: Documenting the Fate of the Lone Woman’s Community,” Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, vol. 36, no. 1 (2016): 97-98, 109-110.

[12] Susan Morris, John R. Johnson, et al., “The Nicoleños in Los Angeles,” 97-98.

[13] Susan Morris, John R. Johnson, et al., “The Nicoleños in Los Angeles,” 97-98, 109-110.

[14] Caire Chiles, 218; Martin Cole, “The Granting of Santa Catalina Island,” in Pio Pico Miscellany (Whittier, CA: Governor Pio Pico Mansion Society, 1978), 67. The horse/silver saddle exchange for the island (and its racist innuendos) appears to have been created later by Catalina’s tourism promoters.

[15] 4-5,000 military servicemen occupied Catalina Island after the U.S. entry into World War II and required all civilians to carry identification at all times. Marcelino Saucedo, Dream Makers and Dream Catchers: The Story of the Mexican Heritage on Catalina Island (Virginia Beach, VA: Donning Co. Publishers, 2008), 63.

[16] Esteban Cházari quoted in Jorge A. Vargas, El Archipiélago del Norte: ¿Territorio de México o de los Estados Unidos? (México, DF: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1993), 94.

[17] Caire Chiles, 218-226; Saucedo, 143.

[18] Caire Chiles, 236

[19] Saucedo, 49. The only break in the Cubs’ spring training in Catalina was from 1942-1945 during World War II. Image from Sam Gnerre, “Spring training with the Cubs on Catalina Island” South Bay History (June 24, 2009), (http://blogs.dailybreeze.com/history/2009/06/24/spring-training-with-the-cubs-on-catalina-island).

[20] Saucedo, 7.

[21] Saucedo, 16-19.

[22] William Wrigley, Jr., quoted in Nov. 13, 1929, Catalina Islander article, quoted by Saucedo, 31. See also page 26 and for band photo page 38.

[23] Saucedo, 16-19, Pastor Lopez and Vernon Lopez quoted on pages 26-27.

[24] Photo by Maria Marquez Sanchez in “Narrated Photo Essay: Maria Marquez Sanchez,” KCET (https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/narrated-photo-essay-maria-marquez-sanchez-on-the-two-sides-of-her-activism).

[25] David Sánchez, Expedition Through Aztlán (La Puente, CA: Perspective Publications, 1978), 182-184.

[26] Samuel Truett, Fugitive Landscapes: The Forgotten History of the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008); Omar S. Valerio-Jiménez, River of Hope: Forging Identity and Nation in the Rio Grande Borderlands (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013).