Mexico’s Claims to the California Channel Islands

Text and original photography by Carlos Francisco Parra

January 20, 2020 (updated July 20, 2020)

|

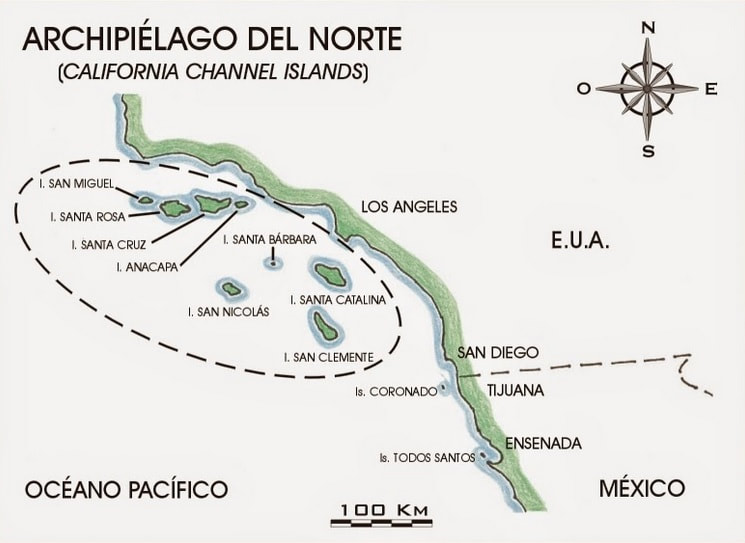

The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the U.S.-Mexico War and created the basis of the two countries’ modern border after it formalized Mexico’s loss of California and much of western North America to the U.S. In redefining the U.S.-Mexican border, Article V of the Treaty detailed the international boundary’s course along the Río Grande and westward across deserts, but its western terminus was only defined as “a point on the coast of the Pacific Ocean distant one marine league due south of the southernmost point of the Port of San Diego.” Unspecified was the fate of an oil-rich island chain just beyond the coast of Southern California, known in English as the Channel Islands and in Mexico as the Archipelago of the North.

|

The Treaty’s ambiguity over the islands’ transfer from Mexico to the U.S. has led white ranchers to proclaim their own kingdoms on the islands while Chicano Brown Berets and Mexican intellectuals have claimed the archipelago for Mexico. Descendants of the archipelago’s first people, the Chumash, have also used the treaty’s ambiguity to attempt to reclaim the islands. As geographer Esteban Cházari affirmed in 1894, the Treaty left the Channel Islands “completely outside of the line indicated by the United States; they are not within the boundaries of that Republic; they were not ceded and remained under Mexican domain.” [1]

QUICK SUMMARY:

|

An Archipelago in Dispute

Mexico’s lost Archipelago of the North is an 8-island chain located just off the coast of Southern California. The islands are as far as 70 miles (110km) from the California mainland (San Nicolas Island) or as close as 16 miles (26 km) (Anacapa Island). Although most of the islands are visible off the coast, most Californians tend to be familiar only with Santa Catalina, the archipelago’s most visited island, accessible from Los Angeles and Long Beach via ferry. Santa Barbara, Anacapa, Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, and San Miguel form part of Channel Islands National Park while the U.S. Navy controls San Clemente and San Nicolas.

The four northern Channel Islands are:

San Miguel Island

The four southern Channel Islands:

The Archipelago under Spanish/Mexican Rule

During the years of Spanish (1769-1821) and Mexican (1821-1848) rule the islands were considered part of the province of Alta California. Spanish sailors first made contact with the archipelago in 1542, but little colonization of the islands took place during the days of Spanish and Mexican Alta California. The lack of seagoing vessels in Alta California made accessing the islands difficult.

During Mexican rule the main economic development of the islands included a failed penal colony and the issuing of land grants. Governors of Alta California issued land grants to Andrés Castillero (1839), José and Carlos Carrillo (1843), and Thomas Robbins (1846) to initiate ranching operations on Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, and Santa Catalina Islands, respectively. None of these projects made much headway. [6]

|

Earlier in 1830 the Mexican government contracted with a U.S. vessel to transport 80 convicted criminals from Acapulco to distant Alta California. When the brig Maria Ester was unable to convince authorities in San Diego or Santa Barbara to accept the convicts, arrangements were made with Governor José Echeandía and the priests at Mission Santa Barbara to settle 30 of the men on Santa Cruz Island’s north shore as well as provide them food and building supplies to start their own penal colony in an area now called Prisoners Harbor.

|

|

Already sick from unsanitary conditions onboard the Maria Ester, the prisoners struggled to form a colony on the island, especially after a fire destroyed their makeshift homes. Unprepared for the island’s windswept weather, the convicts quickly built rafts from whatever materials they could and made the perilous journey to the mainland on open sea. Miraculously, the convicts survived and (after being recaptured and flogged) joined local society. Although their colony failed, the convicts’ history lives on as “Prisoners Harbor” is one of the most visited sites in Channel Islands National Park. [7] The challenges of developing the Channel Islands prevented the archipelago from becoming a more significant part of Mexican Alta California.

|

Mexico’s Claim to the Lost Archipelago

|

After the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) ended the U.S.-Mexico War, the Channel Islands and the rest of Alta California seemingly transferred from Mexico to the U.S. However, the islands’ status under vaguely-worded Article V was not fully identified until the 1890s.

On January 15, 1894, Esteban Cházari presented his colleagues in the Mexican Society for Geography and Statistics a patriotic speech outlining the claims Mexico should pursue to reassert its control over the islands. Cházari argued that the islands were simply not mentioned in the Treaty, itself the result of “the most unjust of wars and the most blatant abuse of might in recorded history.” [9] |

The Channel Islands, Cházari asserted, “were completely outside of the boundary line established by the United States.” [10] Furthermore the islands were beyond the U.S.’s territorial waters (which at the time only extended 3 miles out from the coast). [11] Additionally, the Mexican government’s distribution of land grants on Santa Rosa, Santa Cruz, and Santa Catalina Islands during the 1830s-1840s actively demonstrated Mexican political control of the archipelago – unlike the U.S. government which did not militarily occupy the islands in the 1850s. [12]

|

Cházari concluded his speech saying “the islands which form the Archipelago of the North have never stopped belonging, by clear and just law, to the Mexican Republic; they are instead being invaded by American squatters (upstarts, meddlers, and unlawful occupants).” The Society supported Cházari’s claims through additional research it conducted and in 1894 petitioned President Porfirio Díaz to take action. [14]

|

Chumash and Chicano Claims to the Channel Islands

Ironically the first individuals to claim the islands were not part of the U.S. were White American veterans of U.S. wars. Civil War veteran Captain William Waters proclaimed himself the "King of San Miguel Island" in the 1890s and refused to allow U.S. government surveyors on the island while in the 1930s-1940s island rancher Herbert Lester similarly declared the island his own kingdom.

Read about the "Kingdoms of San Miguel" here.

Although the white American “kings” of San Miguel justified the existence of their island kingdoms on the ambiguity of Article V of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexican Americans and descendants of the Chumash also pointed to Article V as a way of seeking justice.

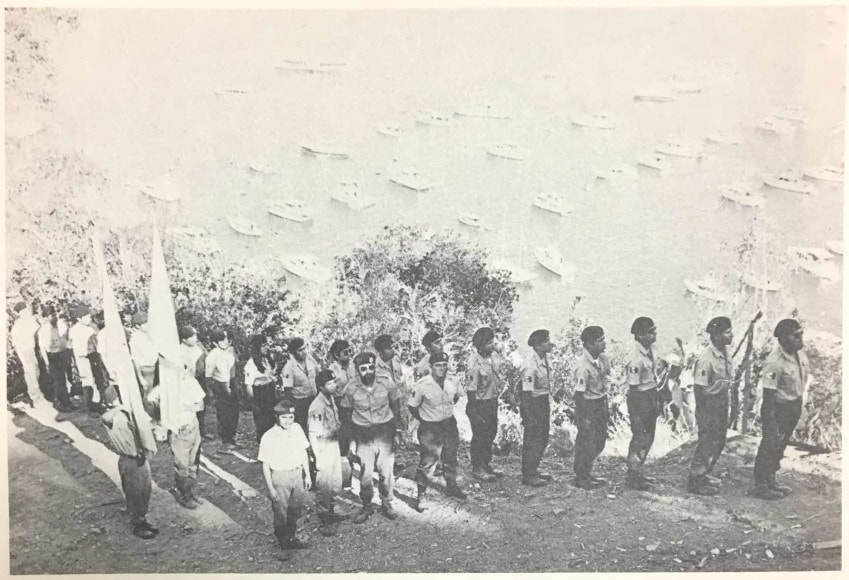

The most famous attempt to assert the Archipelago of the North on Mexican peoples’ behalf (citing the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo) did not take place until the August 30-Sept. 22, 1972 occupation of Catalina Island by the Brown Berets, a Mexican American activist group. Formed to protest anti-Mexican racism in the U.S. Southwest, the Brown Berets were part of the larger 1960s-1970s Chicano movement.

Read about the "Kingdoms of San Miguel" here.

Although the white American “kings” of San Miguel justified the existence of their island kingdoms on the ambiguity of Article V of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexican Americans and descendants of the Chumash also pointed to Article V as a way of seeking justice.

The most famous attempt to assert the Archipelago of the North on Mexican peoples’ behalf (citing the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo) did not take place until the August 30-Sept. 22, 1972 occupation of Catalina Island by the Brown Berets, a Mexican American activist group. Formed to protest anti-Mexican racism in the U.S. Southwest, the Brown Berets were part of the larger 1960s-1970s Chicano movement.

|

David Sánchez, Brown Beret co-founder and Prime Minister, said the occupation’s purpose was to bring attention to the “the bad living conditions for people of Mexican descent who are living in the United States.” Sánchez and 25 other Brown Berets raised the Mexican flag on a hill overlooking Catalina Island’s town of Avalon. Opposed by the island’s Anglo owners and residents, the Brown Berets camped on Catalina for 24 days until their supplies ran out and were ordered to leave by riot police. [16]

Learn more about the Brown Berets on Catalina Island here. |

|

The Berets’ occupation of Catalina brought attention to the islands’ status under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo – a key argument a group of Chumash later used to claim title to Santa Cruz and Santa Rosa Islands. In a case titled United States ex Rel. Chunie v. Ringrose, Chunie Frances Herrera argued that besides inhabiting the islands before European colonization, Article V of the Treaty did not transfer the Channel Islands from Mexico to the U.S. However, in April 1986 the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit denied Chumash title to the islands and affirmed the archipelago’s annexation to the U.S., declaring “neither the United States nor Mexico has ever contested the inclusion of the islands as part of California.” [17]

|

Mexico Abandons its Lost Archipelago

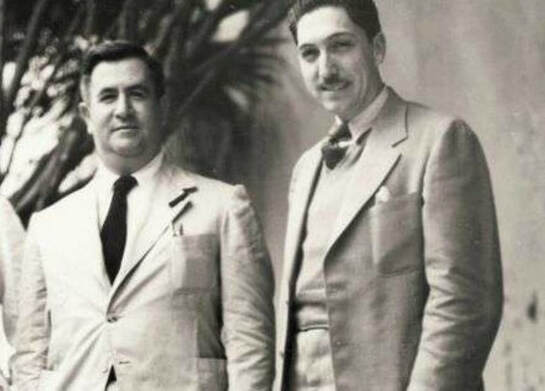

Indeed, as the courts in the Chunie v. Ringrose case affirmed, Mexico never formally claimed the Archipelago of the North after signing the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. In 1944, fifty years after Cházari first contacted the Mexican government regarding the Channel Islands, President Manuel Ávila Camacho formed a six-member commission of geographers, jurists, and historians to study Mexican claims on the archipelago. The Ávila Camacho Commission’s work gained the attention of the California press which feared Mexico was about to reclaim the islands and demand taxes from their residents. [18]

The Ávila Camacho Commission quietly presented its 400-page study to President Miguel Alemán in December 1947. According to historian Jorge Vargas, the Commission affirmed “Mexico lacks rights over the Archipelago of the North” and would likely face an “unfavorable” ruling if it submitted the issue to international arbitration. [20]

|

Despite the public funds that went into the 3-year project, the Commission’s findings have been classified because the Mexican government fears the Mexican people’s backlash. [21] When the Brown Berets occupied Catalina Island they were unaware that the Mexican government had secretly already given up on the archipelago.

|

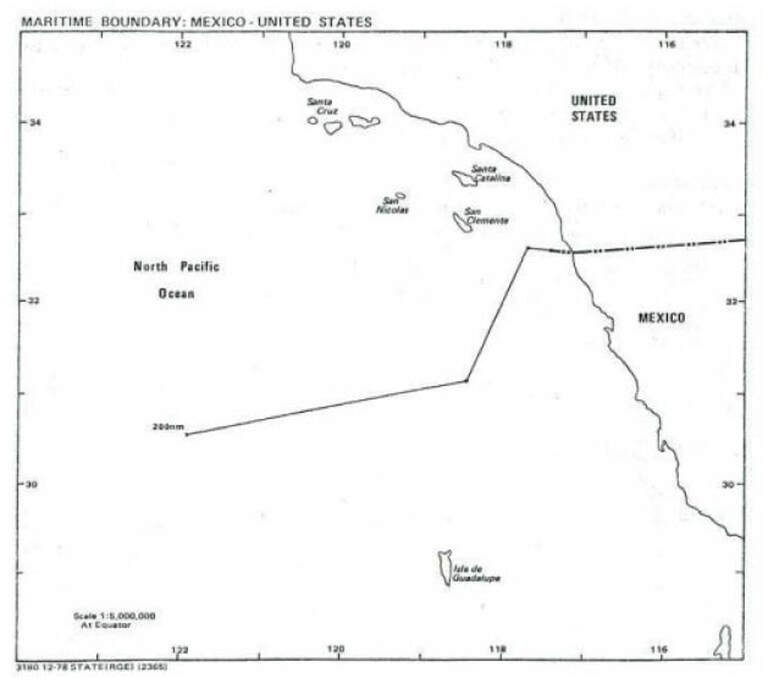

Furthermore, the 1978 U.S. Maritime Boundary Treaty with Mexico outlined the two countries’ sea borders and fully reaffirmed the existing ownership of islands on opposite sides of the maritime border, confirming the California Channel Islands as being part of the U.S. “North of the maritime boundaries established” in the treaty, Mexico could not “claim or exercise for any purpose sovereign rights or jurisdiction over the waters or seabed and subsoil.” The U.S.-Mexican maritime border in the Pacific Ocean is shown below. [22]

Ultimately the Mexican government – whether in the 1890s, the 1940s, or the 1970s – had no desire to pick a fight with the U.S. over the strategic Archipelago of the North and its oil-rich waters.

Conclusion: Sailing Home

It is difficult to image how the U.S.-Mexico relationship would be if the two countries had a maritime border running between California and the Channel Islands. Oil production in the Archipelago of the North would certainly be a priority for the Mexican government, likely creating tensions similar to how industrial pollution between U.S.-Mexican border cities often causes transnational public health problems. If still Mexican soil, the Channel Islands would be Latin America’s extreme northern corner. [23]

The micronation kingdoms of San Miguel, the Chicano Brown Berets’ activism on Santa Catalina, denied Chumash title to the islands in the 1980s, and Cházari’s history research embody the uncertainty of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo’s borders. Mexico’s lost archipelago is a reminder of the constantly changing U.S.-Mexican border.

The micronation kingdoms of San Miguel, the Chicano Brown Berets’ activism on Santa Catalina, denied Chumash title to the islands in the 1980s, and Cházari’s history research embody the uncertainty of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo’s borders. Mexico’s lost archipelago is a reminder of the constantly changing U.S.-Mexican border.

NOTES:

[1] Esteban Cházari quoted in Jorge A. Vargas, El Archipiélago del Norte: ¿Territorio de México o de los Estados Unidos? (México, DF: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1993), 35 and 85.

[2] Map by Víctor Busteros Ángeles, “Día 23, jueves 5-05. Rumbo a Coronado,” Expedición al México de Ultramar (Feb. 13, 2015), (http://mexicodeultramar.blogspot.com/2015_02_13_archive.html).

[3] Image from San Clemente Island (http://www.scisland.org/).

[4] The 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill was influential in the formation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 1970, see Larry Greenemeier, “Gulf Spillover: Will BP's Deepwater Disaster Change the Oil Industry?” Scientific American (June 7, 2010), (https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/molotch-deepwater-environmental-sociology/).

[5] Image of the Helek (Peregrine Falcon) from “Roberta A. Cordero, “Full Circle Chumash Cross Channel in Tomol to Santa Cruz Island,” Wishtoyo Chumash Foundation (https://www.wishtoyo.org/tomol-construction-voyages).

[6] “Island Development,” Camp Internet: Explore the Channel Islands (http://www.rain.org/campinternet/channelhistory/expedition3/santacruz/santacruzranching.html).

[7] Michael Redmon, “Prisoners Harbor,” Channel Islands National Park (https://www.nps.gov/chis/learn/historyculture/prisoners.htm); Frederic Caire Chiles, California’s Channel Islands: A History (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2015), 100; “Prisoners’ Harbor, Santa Cruz Island,” Islapedia (https://www.islapedia.com/index.php?title=Prisoners%E2%80%99_Harbor,_Santa_Cruz_Island)

[8] “Quienes Somos,” Sociedad Mexicana de Geografía y Estadística

(http://smge-mexico.blogspot.com/p/quienes-somos.html)

[9] Vargas, El Archipiélago del Norte, 87.

[10] Vargas, El Archipiélago del Norte, 85.

[11] Vargas, El Archipiélago del Norte, 42; David B. Newsom, “Why the Three-Mile Limit Sank,” Christian Science Monitor (Jan. 26, 1989), (https://www.csmonitor.com/1989/0126/edave.html).

[12] Vargas, El Archipiélago del Norte, 91.

[13] “Edificio Sede,” Sociedad Mexicana de Geografía y Estadística (http://smge-mexico.blogspot.com/p/edificio-sede.html).

[14] Vargas, El Archipiélago del Norte, 37-38 and 94-95.

[15] Photograph from David Sánchez, Expedition Through Aztlán (La Puente, CA: Perspective Publications, 1978), 191.

[16] David Sánchez, Expedition Through Aztlán (La Puente, CA: Perspective Publications, 1978), 180-182, 188-190; Al Martinez, “Judge Asks Berets to Leave – They Do,” Los Angeles Times (Sept. 23, 1972), B-1.

[17] “United States ex Rel. Chunie v. Ringrose,” case decided by U.S. Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit (April 29, 1986), CaseText, (https://casetext.com/case/united-states-ex-rel-chunie-v-ringrose); “Chumash lawsuit against Santa Cruz and Santa Rosa islands,” Islapedia (https://www.islapedia.com/index.php?title=Chumash_lawsuit_against_Santa_Cruz_and_Santa_Rosa_islands).

[18] J. N. Bowman, “The Question of Sovereignty over California's Off-shore Islands,” Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Aug., 1962), 291-301; “Mexico Will Claim Santa Catalina and Other Islands for Tax Levying,” Los Angeles Times (July 23, 1946), A-1 (cropped front page shown).

[19] Image from “Él es el gringo más odiado; no estamos hablando de Trump,” El Debate (Dec. 16, 2016), (https://www.debate.com.mx/mundo/El-es-el-gringo-mas-odiado-no-estamos-hablando-de-Trump-20161216-0100.html)

[20] Vargas, El Archipiélago del Norte, 8-9.

[21] Antonio Carrillo Flores, Mexican Foreign Relations Secretary in 1970, explained the Ávila Camacho Commission felt Mexico did not have enough of a legal claim to the islands 100 years after losing them. Publicizing the Commission’s unfavorable findings was “contrary to the national interest.” Vargas, El Archipiélago del Norte, 157-158.

[22] Other territorial disputes between the two countries – such as the famous diplomatic conflict over the Chamizal strip between Ciudad Juarez and El Paso – took nearly a century to resolve, despite stronger Mexican claims. If the relatively-smaller territory of the Chamizal along the Rio Grande elicited such staunch U.S. resistance, what type of chances would Mexico have in regaining 8 strategic islands off the coast of California, particularly given their valuable offshore oil deposits? Vargas, El Archipiélago del Norte, 154-155. Treaty quoted (and accompanying map) from “U.S. Maritime Boundary Treaty with Mexico 1978,” U.S. Department of State (https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/MB_US-Mexico_1978.pdf).

[23] If part of Mexico today, the Channel Islands would likely be administered as part of the Tijuana Municipality, essentially making Tijuana a direct neighbor to Santa Barbara and Ventura. Perhaps the archipelago’s administration would be similar to Isla Guadalupe, governed by the Ensenada Municipality located 400 kilometers (250 miles) to the northeast.

[2] Map by Víctor Busteros Ángeles, “Día 23, jueves 5-05. Rumbo a Coronado,” Expedición al México de Ultramar (Feb. 13, 2015), (http://mexicodeultramar.blogspot.com/2015_02_13_archive.html).

[3] Image from San Clemente Island (http://www.scisland.org/).

[4] The 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill was influential in the formation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 1970, see Larry Greenemeier, “Gulf Spillover: Will BP's Deepwater Disaster Change the Oil Industry?” Scientific American (June 7, 2010), (https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/molotch-deepwater-environmental-sociology/).

[5] Image of the Helek (Peregrine Falcon) from “Roberta A. Cordero, “Full Circle Chumash Cross Channel in Tomol to Santa Cruz Island,” Wishtoyo Chumash Foundation (https://www.wishtoyo.org/tomol-construction-voyages).

[6] “Island Development,” Camp Internet: Explore the Channel Islands (http://www.rain.org/campinternet/channelhistory/expedition3/santacruz/santacruzranching.html).

[7] Michael Redmon, “Prisoners Harbor,” Channel Islands National Park (https://www.nps.gov/chis/learn/historyculture/prisoners.htm); Frederic Caire Chiles, California’s Channel Islands: A History (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2015), 100; “Prisoners’ Harbor, Santa Cruz Island,” Islapedia (https://www.islapedia.com/index.php?title=Prisoners%E2%80%99_Harbor,_Santa_Cruz_Island)

[8] “Quienes Somos,” Sociedad Mexicana de Geografía y Estadística

(http://smge-mexico.blogspot.com/p/quienes-somos.html)

[9] Vargas, El Archipiélago del Norte, 87.

[10] Vargas, El Archipiélago del Norte, 85.

[11] Vargas, El Archipiélago del Norte, 42; David B. Newsom, “Why the Three-Mile Limit Sank,” Christian Science Monitor (Jan. 26, 1989), (https://www.csmonitor.com/1989/0126/edave.html).

[12] Vargas, El Archipiélago del Norte, 91.

[13] “Edificio Sede,” Sociedad Mexicana de Geografía y Estadística (http://smge-mexico.blogspot.com/p/edificio-sede.html).

[14] Vargas, El Archipiélago del Norte, 37-38 and 94-95.

[15] Photograph from David Sánchez, Expedition Through Aztlán (La Puente, CA: Perspective Publications, 1978), 191.

[16] David Sánchez, Expedition Through Aztlán (La Puente, CA: Perspective Publications, 1978), 180-182, 188-190; Al Martinez, “Judge Asks Berets to Leave – They Do,” Los Angeles Times (Sept. 23, 1972), B-1.

[17] “United States ex Rel. Chunie v. Ringrose,” case decided by U.S. Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit (April 29, 1986), CaseText, (https://casetext.com/case/united-states-ex-rel-chunie-v-ringrose); “Chumash lawsuit against Santa Cruz and Santa Rosa islands,” Islapedia (https://www.islapedia.com/index.php?title=Chumash_lawsuit_against_Santa_Cruz_and_Santa_Rosa_islands).

[18] J. N. Bowman, “The Question of Sovereignty over California's Off-shore Islands,” Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Aug., 1962), 291-301; “Mexico Will Claim Santa Catalina and Other Islands for Tax Levying,” Los Angeles Times (July 23, 1946), A-1 (cropped front page shown).

[19] Image from “Él es el gringo más odiado; no estamos hablando de Trump,” El Debate (Dec. 16, 2016), (https://www.debate.com.mx/mundo/El-es-el-gringo-mas-odiado-no-estamos-hablando-de-Trump-20161216-0100.html)

[20] Vargas, El Archipiélago del Norte, 8-9.

[21] Antonio Carrillo Flores, Mexican Foreign Relations Secretary in 1970, explained the Ávila Camacho Commission felt Mexico did not have enough of a legal claim to the islands 100 years after losing them. Publicizing the Commission’s unfavorable findings was “contrary to the national interest.” Vargas, El Archipiélago del Norte, 157-158.

[22] Other territorial disputes between the two countries – such as the famous diplomatic conflict over the Chamizal strip between Ciudad Juarez and El Paso – took nearly a century to resolve, despite stronger Mexican claims. If the relatively-smaller territory of the Chamizal along the Rio Grande elicited such staunch U.S. resistance, what type of chances would Mexico have in regaining 8 strategic islands off the coast of California, particularly given their valuable offshore oil deposits? Vargas, El Archipiélago del Norte, 154-155. Treaty quoted (and accompanying map) from “U.S. Maritime Boundary Treaty with Mexico 1978,” U.S. Department of State (https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/MB_US-Mexico_1978.pdf).

[23] If part of Mexico today, the Channel Islands would likely be administered as part of the Tijuana Municipality, essentially making Tijuana a direct neighbor to Santa Barbara and Ventura. Perhaps the archipelago’s administration would be similar to Isla Guadalupe, governed by the Ensenada Municipality located 400 kilometers (250 miles) to the northeast.