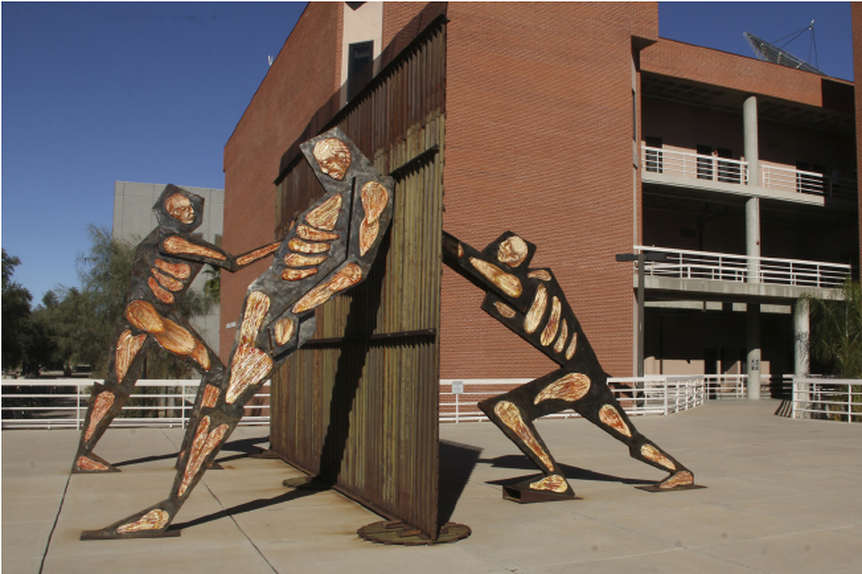

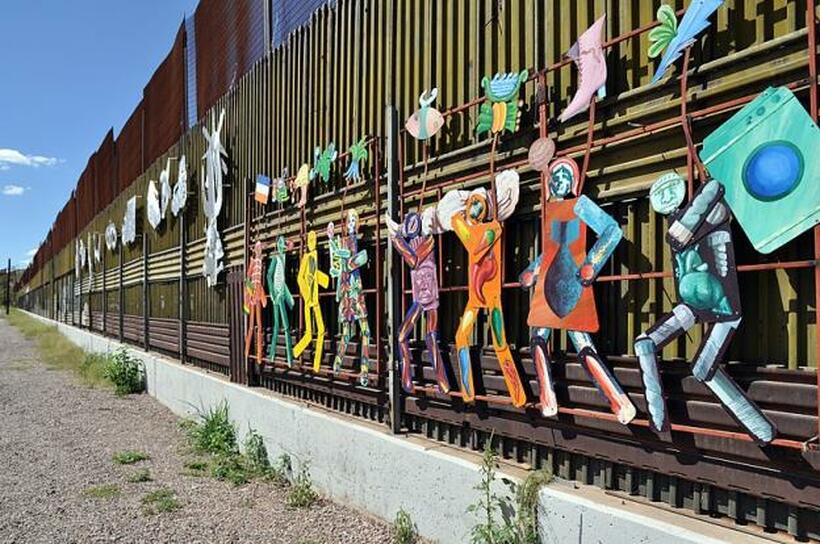

Art is part of the discussion. The border is an issue that art can say a lot about." Along the U.S-Mexican border various artists, using a variety of art forms, have worked to encourage the general public to reflect on the social problems caused by the border’s existence. Among the most noteworthy issues this art explores are transnational migration as well as the use of government force (such as the U.S. Border Patrol) to build up the border. The work of Nogales, Sonora, artists Alberto Morackis and Guadalupe Serrano bears witness to how public art can contribute to a greater awareness of the border’s social problems. Border Dynamics, Nogales, MX and Tucson, AZ (2003)In January 2003 artists Alberto Morackis and Guadalupe Serrano unveiled a steel sculpture artwork composed of different figures interacting with the border wall along Heroica Nogales, Sonora, Mexico’s Calle Internacional. The sculptures in Border Dynamics (Dinámica Fronteriza) weighed 900 pounds each and tried to push down or reinforce the corrugated steel border fence. In Morackis and Serrano’s original vision the four ambiguous sculptures were to have been placed on both sides of the border fence to better illustrate the push-pull character of the militarized border. However, neither Morackis, Serrano, or their sponsors were able to obtain permission from the U.S. Border Patrol (USBP) to place two of the four sculptures on the U.S. side of the fence. According to USBP spokesmen, placing two sculptures on the U.S. side would have required for a guard to be present at all times to prevent young people from cutting themselves with the steel figures’ sharp edges. Additionally, there were concerns the sculptures would be used as ladders by undocumented border crossers. [3] After many months of display in Nogales, the steel sculptures of Border Dynamics were moved to the University of Arizona mall which was supposed to be the first stop of the artwork’s national tour through different universities across the United States. The Beyond Borders Binational Art Foundation, a Tucson-based border art group, sponsored Morackis and Serrano’s work as well as help them put Border Dynamics on display at the U of A. Wells Fargo Bank and the Arizona Commission on the Arts. During its initial exhibition at the U of A, Border Dynamics acquired a replica of the corrugated steel border fence which allowed the artwork to finally have the four steel figures pushing against one another on opposites sides of the fence. According to Tom Whittingslow, founder of Beyond Borders, Morackis and Serrano’s sculptures were the first work in a series of public artworks which would explore border issues along the Arizona-Sonora region, similar to border art between San Diego and Tijuana. Border Dynamics debuted on September 15, 2003, at the UA as part of the university’s Hispanic Heritage Month festivities. [5] Despite the enthusiasm generated by Border Dynamics, the national tour the sponsors at Beyond Borders envisioned did not come to pass due to lack of funding. For a time the steel sculptures were stored away from the public. UA President Peter Likins, however, expressed interest in having Morackis and Serrano’s artwork on permanent display on campus. With the help of the UA Art Museum, Border Dynamics was put on permanent display in 2005 on the northern part of the main UA campus at the entrance to the Harvill Building. According to Whittingslow, the sculptures represent the “atmosphere of xenophobia and fear” that migration between Mexico and U.S. often reflects. “By externalizing these feelings through art, perhaps a common ground can be found. These figures are allegories of how we behave when confronted with barriers-either external or of the mind. In this sense, the sculptures are universal.” [7] Paseo de la Humanidad, Heroica Nogales, Sonora, Mexico (2004)Alberto Morackis once explained that the name of his and Serrano’s art workshop, Taller Yonke (junkyard workshop), originated from the “many junkyards in Nogales (Mexico), and because Mexico is the United States’ junkyard.” The duo’s next work in 2004 used scrap metal to vividly illustrate the nature of the uneven and conflicting relationship between the U.S. and Mexico in Paseo de la Humanidad (Parade of Humanity). UA Art Professor Alfred J. Quiróz collaborated with Morackis and Serrano in bringing the colorful metal murals to life. [9]  The Mexican and U.S. eagles meet in two opposing metal panels placed on the then U.S.-Mexico border fence between Nogales, Arizona, and Nogales, Sonora. The middle panel represents the original historical geographic extent of Mexico prior to the U.S.-Mexico War as well as the presence of the modern-day border fences. Regrettably these panels were removed from the larger metal mural when the U.S. government replaced its border fencing in Nogales in 2011. [10] Composed different metallic panels and human-like figures painted in varying colors and designs, the original Paseo de la Humanidad was one of the most celebrated and noteworthy artworks in Nogales. The Taller Yonke team placed the metal mural on the Mexican side of the fence since “no permission is needed to install artwork on the fence” from the Mexican government. Additionally, Morackis stated, “the United States placed its border wall without any discussion.” [11] In 2011 the U.S. government replaced the corrugated steel fence in Nogales and prohibited incorporation of art on the new barrier, forcing Paseo de la Humanidad to be placed on standalone metal posts a few meters away from the wall [BELOW]. In one part of the mural eight figures can be seen congregating at a metallic post meant to represent the border. Using Aztec symbols as well as the imagery of modern-day mass consumption items, the different figures represent the transnational movement of Latin American migrants and sentiments. On one side of the “border” we can see a group of migrants preparing to cross over the boundary into the U.S. In the original version of Paseo de la Humanidad the metallic post which represented the border was one of the main steel beams which supported the real 1990s-era border fence [ABOVE]. In this part of the mural we can see a mother (with her metallic body covered in roses) carrying her son as she attempts to cross the border. Meanwhile figures coming from the opposing direction are carrying a covered person on their shoulders. The two figures are carrying home a companion migrant who perished in U.S., perhaps just barely during the dangerous desert crossing. The cross-border movement of these transnational migrants was more obvious in Paseo de la Humanidad’s original exhibition. The different metal figures vividly represent the cultural shock between Latin and North America. One figure (with a face resembling that of the Statue of Liberty) also includes a bomb for its torso, missiles for its legs, and bombs for its arms, symbolizing U.S. militarism. The celebrated U.S. symbol of immigration also has a word balloon with unintelligible text in Latin. In another part of the metallic mural one can see a menacing figure dressed in the green uniform of the U.S. Border Patrol shouting something in Latin while waving his police baton at a migrant. Morackis, Serrano, and Quiróz had the Statue of Liberty and USBP figures speaking in Latin (a language unintelligible to the majority of people today) in order to express how strange and foreign the English language can sound to many migrants. According to Guadalupe Serrano, Morackis and Quiróz’s collaborator in Paseo de la Humanidad, the increasing number of migrants deaths in the Sonoran desert in the 2000s influenced his contribution to the metal mural. Serrano wanted their art to serve as a warning for would-be migrants. The menacing face the sun has in this part of the mural reflects the numerous natural dangers migrants face in crossing the desert into the United States. “It's a way for the migrants to see the dangers that are behind the wall in the desert. Does it work? Who knows?” [15]  The presence of “Malverde” (patron folk-saint of Mexican drug traffickers) in the left figure as well as the what appears to be a drug mule (middle figure) show the other face of transborder migration. Besides the significant natural obstacles, migrants face many other violent perils when journeying into the U.S. through the Sonoran Desert. Border art, a genre in of itself which needs greater public and academic attention, represents one of the most transcendental ways in which border residents can express themselves as well as critique the social problems caused by the border, making the type of artwork promoted by Morackis, Serrano, Quiróz and others in the region all the more crucial. NOTES:[1] Margaret Regan, “Artistic Warning: A group including Tucsonan Alfred Quiróz hopes to send a message about border-crossing deaths with their gigantic Nogales border art,” Tucson Weekly, May 13, 2004 (https://www.tucsonweekly.com/tucson/artistic-warning/Content?oid=1076154).

[2] “Border Dynamics,” Ziad Zitoun Blog (http://ziadhelmizitounvisual.blogspot.com/2011/05/border-dynamics-by-guadalupe-serrano.html). [3] Regan, “Artistic Warning," (https://www.tucsonweekly.com/tucson/artistic-warning/Content?oid=1076154). [4] Janice K. Monk “Braided Streams: Spaces and Flows in a Career,” Documents d’Anàlisi Geogràfica Vol. 61, no. 1 (2015), (https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Border-Dynamics-On-each-side-are-two-male-figures-one-pushing-against-the-wall-the_fig2_272433554). [5] Julieta Gonzalez, “’Border Dynamics’ Sculpture Begins National Tour on UA Mall,” UA News, July 21, 2003 (https://uanews.arizona.edu/story/border-dynamics-sculpture-begins-national-tour-on-ua-mall); “Border Dynamics,” University of Arizona Art Museum (http://artmuseum.arizona.edu/public_art/border-dynamics). [6] Photograph by Selena Quintanilla in “’Border Dynamics’: One of UA's massive public art collections,” Daily Wildcat, January 21, 2017 (http://www.wildcat.arizona.edu/article/2017/01/border-dynamics-one-of-uas-massive-public-art-collection). [7] Julieta Gonzalez, “’Border Dynamics’ Sculpture Begins National Tour on UA Mall,” UA News, July 21, 2003 (https://uanews.arizona.edu/story/border-dynamics-sculpture-begins-national-tour-on-ua-mall); “Border Dynamics,” University of Arizona Art Museum (http://artmuseum.arizona.edu/public_art/border-dynamics); “Border Dynamics,” Border by Bryan (Jan. 30, 2011) (https://borderbybryan.wordpress.com/2011/01/30/border-dynamics). [8] Photograph by Steev Hise, “Nogales Border Wall – 7,” Flickr (Nov. 29, 2005), (https://www.flickr.com/photos/steev/68756608/). [9] Regan, “Artistic Warning," (https://www.tucsonweekly.com/tucson/artistic-warning/Content?oid=1076154). [10] Photograph by Hise, “Nogales Border Wall – 7,” (https://www.flickr.com/photos/steev/68756608/) [11] Regan, “Artistic Warning," (https://www.tucsonweekly.com/tucson/artistic-warning/Content?oid=1076154). [12] Edward S. Casey and Mary Watkins, Up Against the Wall: Re-Imagining the U.S.-Mexico Border (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014); “Paseo de la Humanidad” photographed in 2010 for Mariano Castillo, “Judge blocks enforcement of Utah immigration law”, CNN (May 11, 2011), (http://politicalticker.blogs.cnn.com/2011/05/11/judge-blocks-enforcement-of-utah-immigration-law/). [13] Photograph by Jonathan McIntosh, “Wall Mural in Nogales,” Flickr (Sept. 17, 2009), (https://www.flickr.com/photos/jonathanmcintosh/4042291011/). [14] Photograph by McIntosh, “Wall Mural in Nogales,” Flickr (Sept. 17, 2009), (https://www.flickr.com/photos/jonathanmcintosh/4042105926/in/photostream/); Photograph of Alberto Morackis (https://hiveminer.com/Tags/laninea/Interesting). [15] Regan, “Artistic Warning," (https://www.tucsonweekly.com/tucson/artistic-warning/Content?oid=1076154). #borderart #Nogales #Tucson #UA #UniversityofArizona #PaseodelaHumanidad #BorderDynamics #NogalesSonora #Sonora #Arizona #migration #immigration

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Carlos Parra

U.S.-Mexican, Latino, and Border Historian Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed