THE AUGUST 27, 1918 BATTLE OF AMBOS NOGALES

The Real Story of the Border War that led to the First U.S.-Mexican Border Fences (Part II)

Text and Original Photography by Carlos Francisco Parra

November 20, 2017 (updated August 25, 2020)

KEY POINTS: (Part II)

|

|

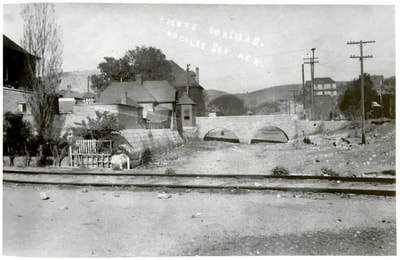

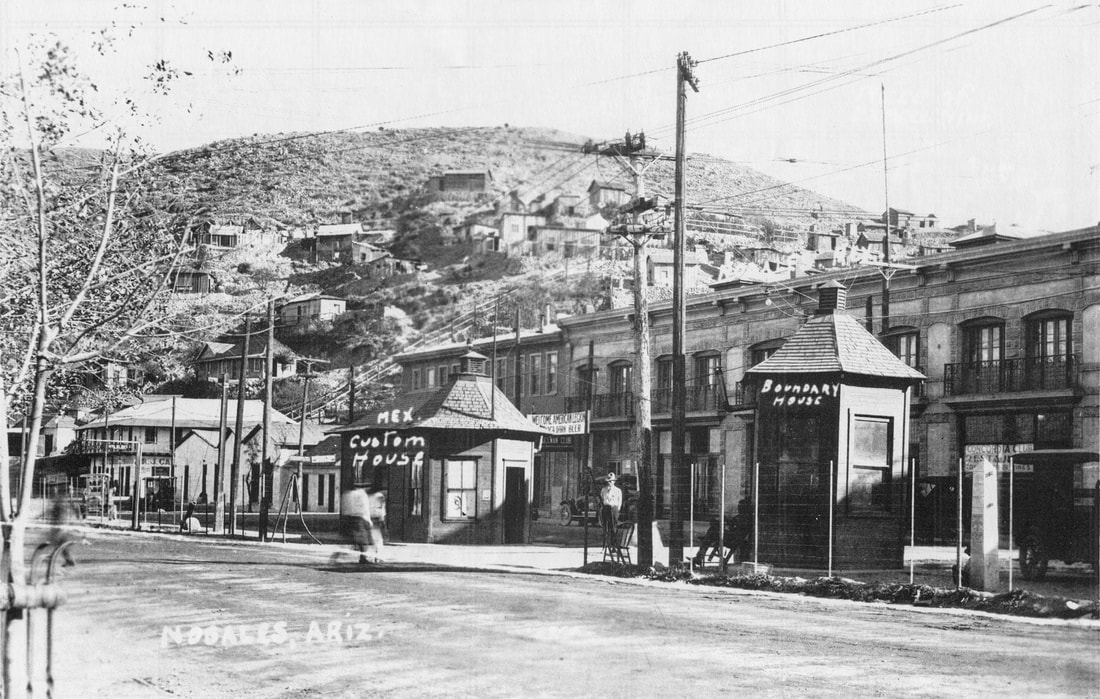

The communities of Ambos Nogales came into existence because of the presence of the U.S.-Mexican border and the economic opportunities of being located along the first railroad which connected Mexico and the U.S. The first customs house (aduana) in Nogales, Sonora, opened in 1880 and quickly became the most important commercial port in the Mexican northwest leading to the construction of a grander aduana in 1887 (shown above).

During the August 27 battle, Mexican soldiers and members of the Ayuntamiento de Nogales raised a white flag on the aduana building’s flagpole to signal their desire for a truce. The 10th Cavalry and 35th Infantry troops in Nogales, Mexico, returned to the U.S. and the border was completely closed until the next afternoon. [1]

During the August 27 battle, Mexican soldiers and members of the Ayuntamiento de Nogales raised a white flag on the aduana building’s flagpole to signal their desire for a truce. The 10th Cavalry and 35th Infantry troops in Nogales, Mexico, returned to the U.S. and the border was completely closed until the next afternoon. [1]

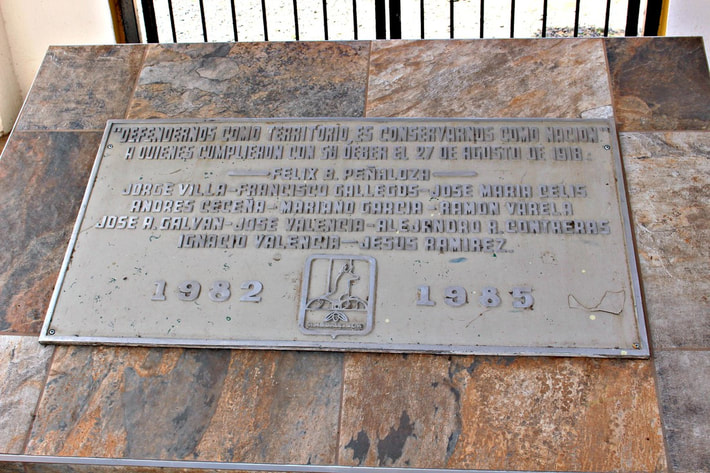

The 1887 Mexican Customs Building shown in the previous image for many years was the symbol of the importance of Nogales as one of Mexico’s main ports. However, the Mexican Government’s modernization of its northern ports of entry through the Proyecto Nacional de Fronteras (PRONAF or National Border Project) led to the demolition of the original elegant building in 1963. The old customs house’s size and location made it inconvenient for the flow of traffic as Nogales grew – in addition to the PRONAF leaders’ lack of perspective – and led to its much regretted demise. A much smaller, all-concrete recreation of the aduana (dedicated in 1985 as the “Plaza Héroes del 27 de agosto”) is located on Calle Ruiz Cortines next to the Ferromex train tracks near the international crossing into the U.S.

Peace Talks between Generals Cabell and Elias Calles

|

|

When the truce flag went up, U.S. troops returned across the line while hillside machine-gunners held their fire. Consul Lawton arranged for early truce talks at the shot-up U.S. Consulate with Lt. Col. Herman, Lieutenant Robert Scott Israel, and Customs Collector Charles Hardy, as well as Captain Alberto Abasolo, Judge Salvador Sandoval, and acting-Presidente Municipal Jesus Palma. The men agreed to stop shooting and close the border until further talks the next day – one of the only times the border has been completely closed in Nogales.

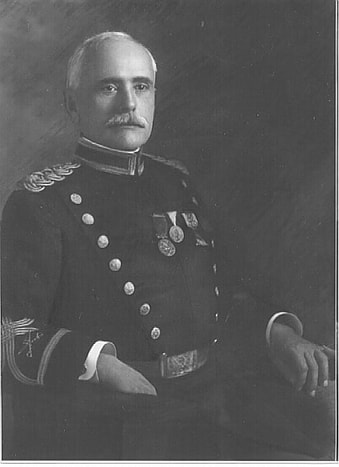

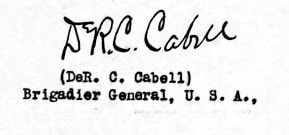

Several hundred Mexicans and some Americans were stranded on opposite sides of the closed border. Miguel Noriega, who was then a 19-year-old carpenter working at Sacred Heart Church in Nogales, Arizona, remembered how strictly the closure of the border was enforced when he tried to cross back to see his parents on the Mexican side. “Several of us tried to cross, but the American soldiers would not let us through.” Noriega and others waited for a chance to cross the line near Boundary Monument 122. “Another young man and I gained courage little by little, and we succeeded in passing through. Once on the Mexican side we didn’t care if they [U.S.] shot at us, but we weren’t shot at.” Noriega got back to his parents on the Mexican side, but many of the Mexican workers who could not cross back spent the night sleeping in Nogales, Arizona parks. All throughout the evening Capt. Abasolo went throughout the town ordering the men to stop shooting. Brigadier General DeRosey Cabell traveled to Nogales from Douglas and Ft. Huachuca, Arizona, with reportedly over 700 reinforcements while Mexican President Venustiano Carranza sent Sonoran Governor Plutarco Elias Calles, with 2000 troops of his own, to investigate and resolve the dispute. At the time of the battle, Calles had been directing the fight against the small rebel group led by Juan Cabral (publishers of México Libre). [2] |

LEFT: Generals Cabell and Calles met here atop a small stone bridge called the Bonillas Bridge on August 28, 1918; an opposing view (RIGHT) of the same location on Calle Internacional and Calle Pesqueira in 2018. The little Bonillas Bridge was removed in 1919.

One version of the Corrido de Nogales states Calles, “like a good Mexican chief met with the U.S. chief who wanted to parley” (“Como un buen jefe mexicano comenzo conferenciar con el jefe americano que quiso parlamentar”). Calles and Cabell met on the Bonillas Bridge to discuss the previous day's violence - ironically this was the same spot where Francisco Mercado was killed on December 31, 1917. Newspaper and government reports of the meeting indicates that both sides, through the help of consuls Garza Zertuche and Lawton, expressed regret and promised to prevent further bloodshed. Calles condemned people on the Mexican side who fought without orders, suggesting they were purposely making trouble on behalf of rebel Juan Cabral. Cabell began an investigation of the battle. [3]

One version of the Corrido de Nogales states Calles, “like a good Mexican chief met with the U.S. chief who wanted to parley” (“Como un buen jefe mexicano comenzo conferenciar con el jefe americano que quiso parlamentar”). Calles and Cabell met on the Bonillas Bridge to discuss the previous day's violence - ironically this was the same spot where Francisco Mercado was killed on December 31, 1917. Newspaper and government reports of the meeting indicates that both sides, through the help of consuls Garza Zertuche and Lawton, expressed regret and promised to prevent further bloodshed. Calles condemned people on the Mexican side who fought without orders, suggesting they were purposely making trouble on behalf of rebel Juan Cabral. Cabell began an investigation of the battle. [3]

|

The Nogales border crossing reopened the afternoon of August 28 amid an awkward peace. In Nogales, Sonora, many damaged stores reopened while small crowds walked around bullet-riddled buildings, wagons, and cars as well as the bodies of dead horses to attend the “unusual amount of funeral processions passing through the streets.” Many families on both sides of the border, afraid of more violence, left Ambos Nogales.

Sporadic gunfire from Mexican shooters continued throughout the night of August 27th and into the late evening of the 28th despite the intervention of Calles and Captain Alberto Abasolo. One bullet hit Private Edward Stiller on duty near the border, sending him to the base hospital. The next morning Stiller snuck out, took a rifle, walked to the border, and fired into houses on the Mexican side, wounding Refugio Garcia, a Mexican soldier standing guard. General Cabell ordered Stiller’s arrest but also warned Governor Calles about their ceasefire agreement. Afterward, Calles and Abasolo went house-by-house confiscating weapons to stop further shooting. [4] |

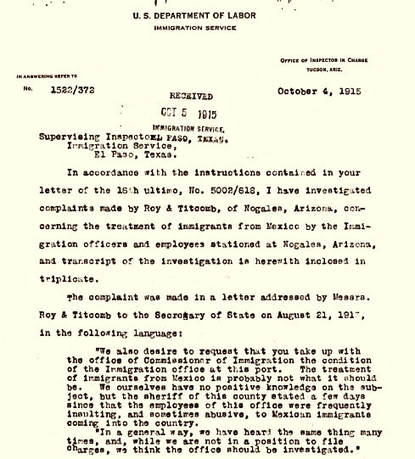

U.S. Army Investigation

In the days after the battle, meetings between Cabell and Calles succeeded in reducing international tensions. On September 1, 1918, the two generals met one last time and agreed to changes to prevent further violence on the Nogales border. Customs and immigration inspectors would be limited to pistols, more patience would be shown by U.S. officials towards Mexican border crossers, and a border fence – 2 miles long and 6 feet tall – would be built to control the movement of people in Nogales. Cabell’s investigation found that the abuse of Mexican border crossers by U.S. immigration and customs officers was a major cause of the violence and recommended the removal certain officers from Nogales in order to improve relations. Cabell’s investigation, and a 1915 U.S. Bureau of Immigration investigation of abuse towards Mexicans in Nogales, show that a considerable level of racial tension existed between many Anglos and Mexicans in the 1910s Nogales border. [5]

Other Army documents also reveal how often U.S. customs and immigration agents shot Mexicans in other bordertowns like El Paso and Calexico in the late 1910s. In one investigation of a skirmish with bandits in Chihuahua, the Army even recommended that the U.S. pay an indemnity to the family of an innocent Mexican bystander U.S. troops killed in the fight. Besides discrimination and abuses of power by U.S. customs and immigration in the 1910s, it is essential that we remember the killing of at least 2 Mexican border crossers in Nogales in the months before August 27. We should also not forget the violent events of 1918 along the Rio Grande border in Porvenir, Texas, and Pilares, Chihuahua. [6]

|

One final look at the inside of the Plaza Héroes del 27 de Agosto inside the commemorative Mexican Customs Building reveals a memorial dedicated to the defenders of Nogales, Mexico. The top of the plaque states “To defend our land is to preserve ourselves as a nation.” Listed alongside Don Félix Peñaloza are 11 other fallen heroes, including customs inspectors Andrés Ceceña and Francisco Gallegos and railroad telegrapher Jorge Villa. Not listed are other confirmed Mexican deaths, such as María Esquivel, Red Cross worker Julia Medina, or Jesús Borboa, one of the older persons killed in the battle and described as “a well-known pioneer citizen of Sonora […] killed as he was crossing Elias Street in front of his home.” [7]

|

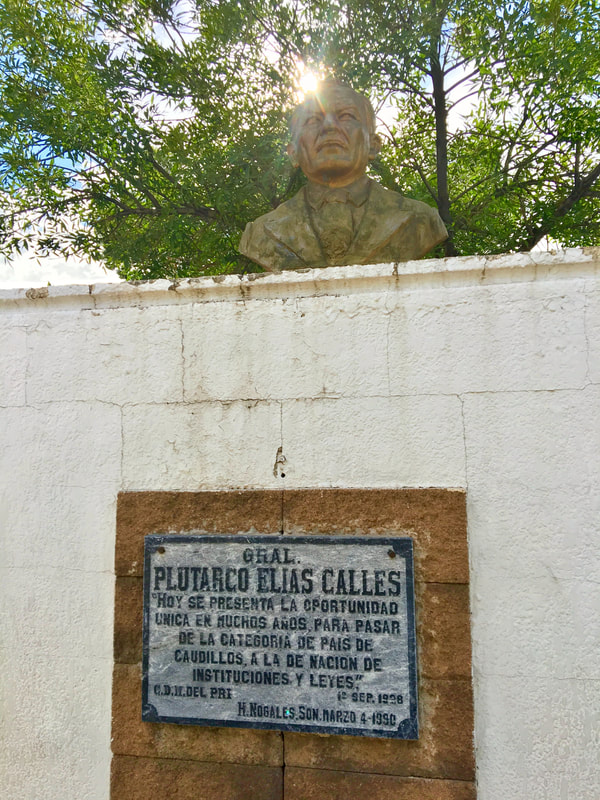

Plutarco Elias Calles and His Impact on Nogales

Calles continued serving as Governor of Sonora, but followed fellow Sonoran Alvaro Obregon into national politics during a bloody 1920 revolution that ended with Obregon as President and Calles as second-in-command as Interior Minister. Calles, a former teacher and barkeeper, became President from 1924-1928 and remained a formidable figure in Mexican politics as the “Jefe Máximo” of the Revolution. One of Calles’s most important legacies is the focus of this 1990 memorial: his role in developing Mexico’s 20th Century political and legal institutions. The peace he helped arrange in Nogales is not as famous as other areas of his career, but his support for a border fence was a key turning point in the history of Nogales and the U.S.-Mexican boundary.

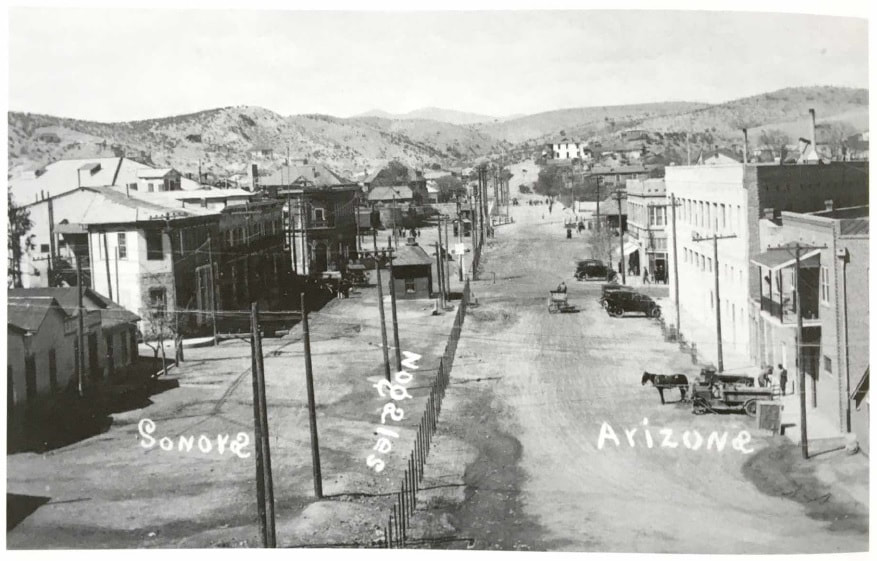

New Normal and the First Permanent Nogales Border Fence

The new dividing fence in the late 1910s/early 1920s (Courtesy of Visit Nogales). The Battle of Ambos Nogales was a major event in the history of the border region, but for many Americans and Mexicans life soon went on as normal. Many downtown merchants on Morley Avenue were pleased that shoppers had replaced the “whizz of bullets” and were seeing business back to normal. Soon the end of World War I on November 11, 1918, also meant the easing of the strict border controls from the summer such as the limits on weekly border crossings and food purchases. The racial tensions that triggered the battle did not fully disappear, but they certainly weakened.

However, there was no turning back once the U.S. Army began building the 2-mile, 6-foot tall border fence in Nogales. Sturdier and longer than either of the fences Maytorena and Peñaloza installed, the new fence cost $5,000 (or $81,054.97 in 2017 dollars) to build and soon succeeded in directing the flow of most traffic between the bordertowns. Many Mexican people protested against the new border fence as it was built during the fall of 1918. [8]

However, there was no turning back once the U.S. Army began building the 2-mile, 6-foot tall border fence in Nogales. Sturdier and longer than either of the fences Maytorena and Peñaloza installed, the new fence cost $5,000 (or $81,054.97 in 2017 dollars) to build and soon succeeded in directing the flow of most traffic between the bordertowns. Many Mexican people protested against the new border fence as it was built during the fall of 1918. [8]

U.S. Memory of the Battle of Ambos Nogales

U.S. Army participants of the Battle of Nogales were eligible for the Mexican Service Medal and Ribbon, a commendation only awarded for significant Mexico-related battles between 1911-1919.

10th Cavalry First Sergeants Thomas Jordan and James T. Penney also received military commendations for taking command of their troops during the battle, especially for Sergeant Jordan who carried his wounded white commanding officer to safety. Although often segregated in Nogales, Arizona public spaces, the 10th Cavalry Buffalo Soldiers were praised by the Nogales Herald in a brief paragraph under the “Sidelights of Battle” coverage of the border war. “Hurrah for the 10th Cavalry. These lads of color hurried to and fro, their rifles spitting lead at the enemy. They are highly spoken of by the entire Nogales public and are complimented for their bravery.” After battle the all-white 35th Infantry left Nogales and was succeeded at Camp Little by the 25th Infantry Regiment, a segregated black unit like the 10th Cavalry. [9]

10th Cavalry First Sergeants Thomas Jordan and James T. Penney also received military commendations for taking command of their troops during the battle, especially for Sergeant Jordan who carried his wounded white commanding officer to safety. Although often segregated in Nogales, Arizona public spaces, the 10th Cavalry Buffalo Soldiers were praised by the Nogales Herald in a brief paragraph under the “Sidelights of Battle” coverage of the border war. “Hurrah for the 10th Cavalry. These lads of color hurried to and fro, their rifles spitting lead at the enemy. They are highly spoken of by the entire Nogales public and are complimented for their bravery.” After battle the all-white 35th Infantry left Nogales and was succeeded at Camp Little by the 25th Infantry Regiment, a segregated black unit like the 10th Cavalry. [9]

Capt. Joseph Dent Hungerford, a white officer in the segregated African American 10th Cavalry, was not yet 24 when he was shot in the heart leading a charge against sniper fire coming from a towering hill on the Mexican side of the border. A native of Washington, D.C., Hungerford was laid to rest in Section 3 of Arlington National Cemetery.

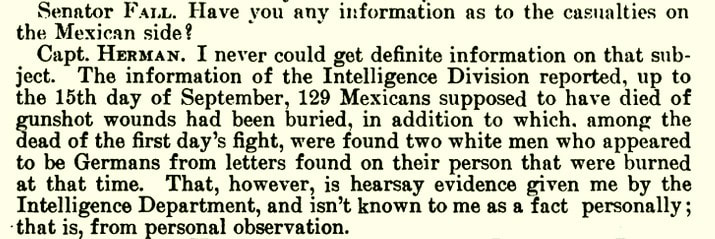

The Battle of Ambos Nogales has been almost completely forgotten on the U.S. side but when it is remembered it is remarkably different from what U.S. newspapers and government documents at the time of the battle recorded. Although the U.S. investigation into the battle concluded that Mexican civilians fought on their own without apparent coordination and that anger at the harassment and killing Mexican border crossers by the U.S. was a major cause of the battle, some Americans later claimed German spies provoked the battle. Though commended for his actions in the battle, by February 1920 Lt. Colonel Fred Herman was a captain stationed in El Paso when he told a congressional committee that Germans directed the Mexican combatants. Herman also alleged Félix Peñaloza had a rifle in his hand when he was killed. There is no mention at all of German involvement in the Army investigation’s findings (which include an endorsement by Herman himself) and the claim of Peñaloza being a combatant is easily disproved by numerous accounts to the contrary. [10]

In the passage shown here, Herman told the committee that the bodies of “two white men who appeared to be Germans” were burned in Nogales, Mexico, after the battle along with letters they carried written in German. Although admitting the evidence was “hearsay”, Herman’s new version of events stuck on the U.S. side, starting with Edward Glass’s History of the Tenth Cavalry (1921). Glass, focusing primarily on the longer history of the 10th Cavalry, based his discussion of the battle heavily on Herman’s problematic congressional testimony. The Herman-Glass version was then repeated in later military history books by Harold Wharfield (1965) and Clarence Clendenen (1969) as well as the 3-issue 1990s Huachuca Illustrated history magazine by James Finley. No evidence exists in U.S. or Mexican archives to support the claim that the Mexican people of Nogales battled the U.S. because German spies instructed them to. According to Glass, German spies had influence over the “fertile soil of the Mexican mind” but everyday border violence in Nogales, such as the routine abuse and killing of Mexicans by U.S. border guards, was influential all on its own. [11]

Despite the impact the battle had on creating the border we know today, there are no monuments on the U.S. side commemorating the battle and one can grow up attending Nogles, Arizona, schools without even knowing this important border war occurred at all, much less why and how this history is still relevant.

Despite the impact the battle had on creating the border we know today, there are no monuments on the U.S. side commemorating the battle and one can grow up attending Nogles, Arizona, schools without even knowing this important border war occurred at all, much less why and how this history is still relevant.

El Panteón de los Héroes: Hallowed Ground

The death toll of the Battle of Ambos Nogales varies depending on the source. On the U.S. side, 3 U.S. servicemen and 1 civilian were killed with 27 soldiers and 1 civilian wounded. The U.S. estimates of Mexican casualties at 129 deaths and 300 wounded – if accurate, these casualties were significant given that only 3,865 people lived in Nogales, Sonora between 1916-1920. According to Consul Garza Zertuche’s report, 15 Mexican deaths were registered in the battle. The two public monuments dedicated to the Battle of August 27 in Nogales, Sonora list 12 dead among the Mexican defenders – but no mention of the women, children or other individuals who may have been killed in the fighting. It is difficult to make an accurate and definitive accounting of the deaths on the Mexican side, but if the U.S. estimate seems excessively high so does the official Mexican report seem excessively low. As mentioned before, María Esquivel's grave at the Panteón de los Héroes is physical proof that the most commonly-cited casualty lists used by Mexican officials were leaving some victims of the violence out of their death counts. [12]

A view of the row of graves of participants in the August 27 Battle of Ambos Nogales in the Panteón de los Héroes. According to the Corrido de Nogales, “He who dies for his Nation dies with full honor, the Tri-color flag accompanies him to the grave” (“El que muere por su Patria muere con todo el honor, al sepulcro lo acompaña, el pabellón tricolor”).

Presidente Peñaloza’s widow Paulita raised money for a worthy commemoration of the dead killed during the Nogales border war. Located in a row, near the Panteón’s entrance, at least 5 of the Mexican dead were buried in the then spacious cemetery: María Esquivel (later joined by Alejandro Esquivel), Jorge Villa, Francisco Gallegos, Félix Peñaloza, and Andrés Ceceña. The Panteón de los Héroes has nearly filled to capacity in the century since the defenders’ deaths – with most of the cemetery’s interred residents’ own families passing away over time, signs of neglect mark the older decaying and sometimes collapsing tombs. While dwindling crowds on Día de los Muertos make up the bulk of the Panteón’s visitors today, the Ayuntamiento de Nogales hosts small ceremonies at the gravesites of the August 27 defenders and continually maintains the tombs of the confirmed defenders.

|

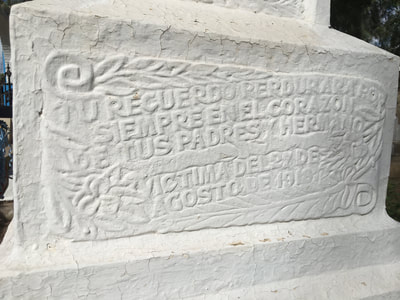

The grave of Maria Esquivel – many of her family members are buried nearby. 17-year old Maria Esquivel’s grave at the Panteon de los Heroes is evidence that more people were killed on the Mexican side than is commemorated in public monuments. Gil, most likely Maria’s younger brother, was buried next to her by their parents upon his death at age 19 in 1921 (BELOW).

|

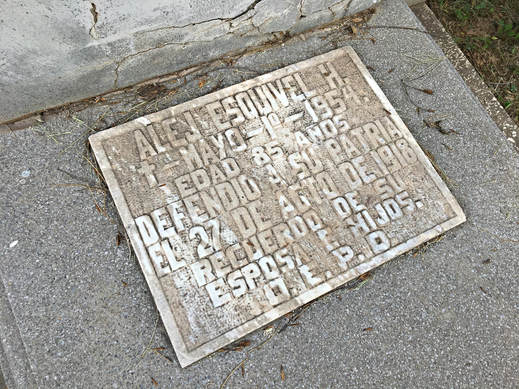

An image of the crucified Christ watches over Alejandro Esquivel’s tomb which is located next to María Esquivel’s grave (BELOW). Credited as having “defended his country on August 27, 1918”, Alejandro Esquivel survived the battle, raised a family and lived until his death in 1954, aged 85. Was Don Alejandro María Esquivel’s father? What was his role in the battle?

|

Francisco Gallegos, one of the Mexican customs agents who encouraged Zeferino Gil Lamadrid to keep walking and who fired at U.S. border inspectors and soldiers at the start of the Nogales border war, is watched over by a figure of the Christ Child set atop elegant columns.

|

|

Jorge Villa, a telegrapher for the Southern Pacific de Mexico Railroad, joined the battle just after the first shots rang outside the train station located near International Street. Villa died age 33 on August 27, 1918, only two weeks shy of his son Jorge Villa Araiza’s birth. Villa’s grandsons Cesar and Javier Villa follow their father’s tradition of visiting their grandfather’s tomb during commemorations of the battle. “One feels great pride having such a significant grandfather and father,” Javier Villa said in 2016. Valencia Aurelia Villa, who may have been the elder Jorge’s sister, is buried along with Jorge in the same tomb. [13]

|

Numerous coats of paint have made some of the text on Jorge’s epitaph is difficult to make out, but upon closer look we can see the grave was dedicated by his parents, wife, and brothers. Perhaps as a sign of the binational culture of the U.S.-Mexican border region, Jorge Villa’s epitaph ends with a “RIP” rather than a Spanish-language “QEPD” (Que en paz descanse).

The final resting place of the fallen presidente municipal has changed colors between its white-hued paint in 2008 to its more golden-colored coating in 2017. According to Mexican Consul Garza Zertuche’s reports, José Celis – a janitor at the Nogales, Sonora, Palacio Municipal – was killed during the battle as well. Did he try to help Peñaloza calm the public during the battle?

Many businesses in Nogales, Sonora, closed on August 29, 1918, for Félix B. Peñaloza’s “much-attended” funeral. Numerous government workers and private citizens paid their respects to Peñaloza and his widow Paulita through many “condolence speeches.” Peñaloza’s sacrifice was even mentioned in President Venustiano Carranza’s annual address to the Mexican Congress on September 1. Peñaloza’s elegant grave states that he “lives on in the hearts of Mexicans grateful for his sacrifice in defense of the nation’s honor on August 27, 1918 – RIP – His Wife Dedicates this Memorial, P.M. widow of P.” Paulita Peñaloza dedicated the grave. [14]

|

At the end of the Mexican defenders’ row of tombs is Andrés Ceceña – a grave surrounded by other Ceceña family tombs and distinguished by a tile-photograph we have encountered earlier in our walk through history. Although there is no date for the image, Andrés’s appearance is that of a youthful man staring straight at the camera. The passage of time makes putting the pieces of the Battle of Ambos Nogales difficult, but images like this remind us of the youth of most of the lives the U.S.-Mexican violence cut short, such as María Esquivel and Jorge Villa.

|

Paulita Peñaloza and the Monumento a los Héroes

|

The widowed Paulita Peñaloza proved to be a tireless advocate for public commemoration of the battle and its legacy. According to historian Pablo Lechuga Bórquez, Doña Paulita worked with the community for 3 years to raise money for a dignified Monument to the Heroes. The monument was dedicated in 1922 in the “Plaza 13 de julio” near the border. The monument was relocated three times before reaching its current location near the main public bus stop in downtown Nogales, Mexico. The memorial’s current location on Avenida López Mateos is a result of the early 1960s PRONAF border modernization project. The Monumento a los Héroes features an inscription of the names of the 12 defenders recognized by the Ayuntamiento de Nogales as having died against the U.S., a memorial plaque, and a sculpture of the Mexican national seal.

|

An obscure event on both sides of the border fence the Battle of Ambos Nogales helped create, it is in the Sonoran bordertown that the battle is more remembered. The PRONAF project’s urban redevelopment of Nogales at least allowed for municipal and state leaders to remind the Mexican Congress of the city’s history in its defense of the national honor. On August 12, 1961, the Mexican Congress officially declared the growing bordertown the “Heroic City of Nogales”, joining other cities across Mexico like Veracruz and Puebla also classified as “heroic” because of their role in military confrontations against foreign invaders.

Full Text of the Corrido de Nogales

As we have already seen, the Corrido de Nogales is an important source of information on the Battle of Ambos Nogales. Despite the anonymity of its composer – lost to history through passage of time – the corrido is another way to learn about the battle and the people it involved. The battle may not have been the U.S. military defeat it describes, but the corrido’s richness evident in the feelings and smaller stories it details. The following lyrics are from a collection of corridos published in the 1998 book Corrido Histórico Mexicano. Vol. 3: Voy a cantarles la historia, 1916-1924.

|

Valientes nogalenses

hicieron su deber pelearon con los gringos hasta morir o vencer. Mil novecientos dieciocho siempre te tendré grabado ese pueblo de Nogales con los gringos han peleado. Comenzaron a pelear a las ocho de ese día, se escucharon por la línea tiros de fusilería. Al cruzar un mexicano la línea divisoria le pegó un balazo un gringo, fue el principio de la historia. Cumpliendo con su deber, Peñaloza corrió luego a la línea divisoria a ver si calmaba al pueblo. Pero luego lo miraron los malos americanos, ahí quedo bien tirado en el suelo mexicano. Eran mil quinientos gringos, todos eran federales y no los dejó avanzar ese pueblo de Nogales. |

Una caballería de negros

que venía entrando voraz, ahí quedaron tirado el resto corrió pa’ tras. Hirieron a dos mujeres, las balas americanas, y dijeron “No hay cuidado, somos puras mexicanas.” El que muere por su Patria, muere con todo honor, al sepulcro lo acompaña el pabellón tricolor. También don José Salcido, haciéndose respetar, haciéndose a sus trincheras pa’ poderlos tirotear. Valientes nogalenses hicieron su deber, pelearon con los gringos hasta morir o vencer. El que muere por su Patria muere con todo el honor, al sepulcro lo acompaña, el pabellón tricolor. |

|

The 2002 Heroes and Horses recording of the “Corrido de Nogales” by Robert Lee Benton Jr. and Oscar Gonzalez, with its version of the iconic corrido's lyrics.

|

|

Finale: Legacy of the Battle of Ambos Nogales

It is in a community which highly values its binational relationship that the first border fences on the Mexican-U.S. international boundary went up, first from August-December 1915, again in July 1918 and then permanently in fall 1918 with a 6-foot tall, 2-mile long fence. It was hoped by U.S. and Mexican officials that better controlling where people could enter and exit between the countries would prevent future violence. Ambos Nogales would see many more fences and walls between them over the century that followed. The Nogales border war helped create the highly-controlled U.S.-Mexican border we know today. After Nogales, the U.S. Army built fences in Naco and Douglas, Arizona, later in 1918. Distant Calexico, California followed suit in 1919.

The Battle of Ambos Nogales led to the fences and walls that divide the two Nogales today

The Battle of Ambos Nogales forever changed the United States and Mexico border. A world without borders or border walls might not be imaginable for us today, but in a different time, before the Mexican Revolution, before World War I and, most importantly, before racial tensions and summer 1918 Nogales border war, there were none. In addition to its regional importance, the battle – with stories of bravery and sacrifice involving individuals as varied as the Mexican women of Nogales, the Buffalo Soldiers, Félix Peñaloza, and a future Mexican President – is a central part of the history of the Nogales community and the U.S.-Mexican border region.

¡Que vivan los valientes Nogalenses!

Acknowledgements:

Archivo Histórico de H. Nogales, Sonora, México

Arizona Historical Society (Tucson, AZ)

National Archives and Records Center (Washington, D.C., and College Park, MD)

Pimeria Alta Historical Society (Nogales, AZ)

University of Arizona McNair Program

Arizona Historical Society (Tucson, AZ)

National Archives and Records Center (Washington, D.C., and College Park, MD)

Pimeria Alta Historical Society (Nogales, AZ)

University of Arizona McNair Program

Suggested Reading:

Arreola, Daniel D. Postcards from the Sonora Border Visualizing Place Through a Popular Lens, 1900s-1950s. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 2017.

Flores García, Silvia Raquel. Nogales: un siglo en la historia. Hermosillo, SON: INAH-SEP, Centro Regional del Noroeste, 1987.

Parra, Carlos F.” Valientes Nogalenses: The 1918 Battle Between the U.S. and Mexico That Transformed Ambos Nogales.” Journal of Arizona History, Vol. 51, (Spring 2010).

Rochlin, Fred and Harriet. “The Heart of Ambos Nogales: Boundary Monument 122,” Journal of Arizona History, vol.17 (Summer 1976), pp. 161-80.

Suárez Barnett, Alberto. Mi Historia . . . Nuestra Historia: 1884-1918-2007. H. Nogales, SON: Imagen Digital del Noroeste, 2007.

St. John, Rachel C. Line in the Sand: A History of the Western U.S.-Mexico Border. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013.

Flores García, Silvia Raquel. Nogales: un siglo en la historia. Hermosillo, SON: INAH-SEP, Centro Regional del Noroeste, 1987.

Parra, Carlos F.” Valientes Nogalenses: The 1918 Battle Between the U.S. and Mexico That Transformed Ambos Nogales.” Journal of Arizona History, Vol. 51, (Spring 2010).

Rochlin, Fred and Harriet. “The Heart of Ambos Nogales: Boundary Monument 122,” Journal of Arizona History, vol.17 (Summer 1976), pp. 161-80.

Suárez Barnett, Alberto. Mi Historia . . . Nuestra Historia: 1884-1918-2007. H. Nogales, SON: Imagen Digital del Noroeste, 2007.

St. John, Rachel C. Line in the Sand: A History of the Western U.S.-Mexico Border. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013.

Notes:

[1] Image, México en Fotos, http://www.mexicoenfotos.com/mobile/city.php?album=vintage&province=sonora&city=nogales&page=4

[2] “Yaqui Indians in Mountains After Battle,” Arizona Republican, Sep 1, 1918; “No Excitement Today on Either Side,” Tucson Citizen, August 28, 1918; “Gen. P.E. Calles, [10/31/24],” Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/npcc.12550/; “Miguel Noriega, Memories of the 1918 Battle at Nogales,” in Oscar J. Martínez, Fragments of the Mexican Revolution: Personal Accounts from the Border (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1983): 197-198. In the 1950s Mr. Noriega founded the Noriega Funeral Home, a well-known business in Nogales, Sonora.

[3] “Yaqui Indians in Mountains After Battle,” Arizona Republican, Sep 1, 1918

[4] “Los Sucesos de Nogales, Sonora,” El Tucsonense, August 31, 1918.

[5] Image, “DeRosey Cabell,” Wikitree, https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Cabell-23

[6] “Allegations of Abuse of Mexicans by Immigration Inspectors,” Box 2307, Record Group 85, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[7] “Second Battle of Nogales,” Border Vidette (Nogales, AZ), August 31, 1918; “Los Sucesos de Nogales, Sonora,” El Tucsonense, August 31, 1918.

[8] Image 30, Visit Nogales, http://www.visit-nogales.com/historia.html; “1918 dollars in 2017,” In 2013 Dollars.com (http://www.in2013dollars.com/1918-dollars-in-2017)

[9] “Sidelights of Battle,” Nogales Herald, August 29, 1918.

[10] Image, Arlington National Cemetery Explorer, http://ancexplorer.army.mil/publicwmv/

[11] Investigation of Mexican Affairs. 66th Congress, 2nd session (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1920), vol. 2, p.1816; E. L. N. Glass, History of the Tenth Cavalry, 1866-1921 (reprint, Fort Collins, Colo.: Old Army Press, 1972), p. 83-86; Harold B. Wharfield, 10th Cavalry and Border Fights (published by the author, El Cajon, CA, 1965); Clarence Clendenen, Blood on the Border: The United States Army and the Mexican Irregulars (London: Macmillan, 1969); . Herman’s claims rest on a letter a Mexican under an assumed name reportedly dropped off at Camp Little before the August 27 battle. Supposedly angry at not being paid for being a soldier in Francisco Villa’s army, the unnamed informant warned of an imminent attack on Nogales. To date, I have not found a copy of this alleged letter or any other evidence in the military or diplomatic papers of the U.S. National Archives or the Pimeria Alta Historical Society to support the claims of a German conspiracy in Nogales. There are also no documented personal eye-witness accounts from specific individuals on either side to corroborate the claims of German officers leading the Nogales fighters. The U.S. Army investigation on the battle makes no mention of this letter despite it being a crucial piece of evidence.

[12] Carlos F. Parra, “Valientes Nogalenses: The 1918 Battle Between the U.S. and Mexico That Transformed Ambos Nogales,” Journal of Arizona History, Vol. 51, (Spring 2010): 2.

[13] Marco A. Flores, “Presentes nietos de ciudadano héroe de la Gesta Heroica de Nogales en festejos,” Infonogales, August 27, 2016, https://infonogales.com/2016/08/27/presentes-nietos-de-ciudadano-heroe-de-la-gesta-heroica-de-nogales-en-festejos/.

[14] “Los Sucesos de Nogales, Sonora,” El Tucsonense, August 31, 1918; Venustiano Carranza, “Discurso de Venustiano Carranza al abrir las sesiones ordinarias del Congreso,” 500 Años de México en Documentos, http://www.biblioteca.tv/artman2/publish/1918_207/Discurso_de_Venustiano_Carranza_al_abrir_las_sesio_1268.shtml

[15] Marco A. Flores, “Presentes nietos de ciudadano héroe de la Gesta Heroica de Nogales en festejos,” Infonogales, August 27, 2016, https://infonogales.com/2016/08/27/presentes-nietos-de-ciudadano-heroe-de-la-gesta-heroica-de-nogales-en-festejos/.

[16] Image, Cuauhtemoc Galindo Twitter Account, August 28, 2017, https://twitter.com/TemoGalindo/status/902350568009728002; “Defendamos Nogales Con Inteligencia“, Nuevo Día (Heroica Nogales, Sonora), August 28, 2017, http://nuevodia.com.mx/2017/08/28/defendamos-nogales-con-inteligencia-temo/.

#usmexicoborder #border #borderlands #mexicanborder #lafrontera #zonafronteriza #nogales #ambosnogales #battleofambosnogales #battleofnogales #batalladenogales #batalladel27deagosto #gestaheroica #gestaheroicadel27deagosto #arizona #sonora #nogalessonora #nogalesarizona #history #historia #borderwall #borderfence #murofronterizo #cercofronterizo

[2] “Yaqui Indians in Mountains After Battle,” Arizona Republican, Sep 1, 1918; “No Excitement Today on Either Side,” Tucson Citizen, August 28, 1918; “Gen. P.E. Calles, [10/31/24],” Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/npcc.12550/; “Miguel Noriega, Memories of the 1918 Battle at Nogales,” in Oscar J. Martínez, Fragments of the Mexican Revolution: Personal Accounts from the Border (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1983): 197-198. In the 1950s Mr. Noriega founded the Noriega Funeral Home, a well-known business in Nogales, Sonora.

[3] “Yaqui Indians in Mountains After Battle,” Arizona Republican, Sep 1, 1918

[4] “Los Sucesos de Nogales, Sonora,” El Tucsonense, August 31, 1918.

[5] Image, “DeRosey Cabell,” Wikitree, https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Cabell-23

[6] “Allegations of Abuse of Mexicans by Immigration Inspectors,” Box 2307, Record Group 85, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[7] “Second Battle of Nogales,” Border Vidette (Nogales, AZ), August 31, 1918; “Los Sucesos de Nogales, Sonora,” El Tucsonense, August 31, 1918.

[8] Image 30, Visit Nogales, http://www.visit-nogales.com/historia.html; “1918 dollars in 2017,” In 2013 Dollars.com (http://www.in2013dollars.com/1918-dollars-in-2017)

[9] “Sidelights of Battle,” Nogales Herald, August 29, 1918.

[10] Image, Arlington National Cemetery Explorer, http://ancexplorer.army.mil/publicwmv/

[11] Investigation of Mexican Affairs. 66th Congress, 2nd session (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1920), vol. 2, p.1816; E. L. N. Glass, History of the Tenth Cavalry, 1866-1921 (reprint, Fort Collins, Colo.: Old Army Press, 1972), p. 83-86; Harold B. Wharfield, 10th Cavalry and Border Fights (published by the author, El Cajon, CA, 1965); Clarence Clendenen, Blood on the Border: The United States Army and the Mexican Irregulars (London: Macmillan, 1969); . Herman’s claims rest on a letter a Mexican under an assumed name reportedly dropped off at Camp Little before the August 27 battle. Supposedly angry at not being paid for being a soldier in Francisco Villa’s army, the unnamed informant warned of an imminent attack on Nogales. To date, I have not found a copy of this alleged letter or any other evidence in the military or diplomatic papers of the U.S. National Archives or the Pimeria Alta Historical Society to support the claims of a German conspiracy in Nogales. There are also no documented personal eye-witness accounts from specific individuals on either side to corroborate the claims of German officers leading the Nogales fighters. The U.S. Army investigation on the battle makes no mention of this letter despite it being a crucial piece of evidence.

[12] Carlos F. Parra, “Valientes Nogalenses: The 1918 Battle Between the U.S. and Mexico That Transformed Ambos Nogales,” Journal of Arizona History, Vol. 51, (Spring 2010): 2.

[13] Marco A. Flores, “Presentes nietos de ciudadano héroe de la Gesta Heroica de Nogales en festejos,” Infonogales, August 27, 2016, https://infonogales.com/2016/08/27/presentes-nietos-de-ciudadano-heroe-de-la-gesta-heroica-de-nogales-en-festejos/.

[14] “Los Sucesos de Nogales, Sonora,” El Tucsonense, August 31, 1918; Venustiano Carranza, “Discurso de Venustiano Carranza al abrir las sesiones ordinarias del Congreso,” 500 Años de México en Documentos, http://www.biblioteca.tv/artman2/publish/1918_207/Discurso_de_Venustiano_Carranza_al_abrir_las_sesio_1268.shtml

[15] Marco A. Flores, “Presentes nietos de ciudadano héroe de la Gesta Heroica de Nogales en festejos,” Infonogales, August 27, 2016, https://infonogales.com/2016/08/27/presentes-nietos-de-ciudadano-heroe-de-la-gesta-heroica-de-nogales-en-festejos/.

[16] Image, Cuauhtemoc Galindo Twitter Account, August 28, 2017, https://twitter.com/TemoGalindo/status/902350568009728002; “Defendamos Nogales Con Inteligencia“, Nuevo Día (Heroica Nogales, Sonora), August 28, 2017, http://nuevodia.com.mx/2017/08/28/defendamos-nogales-con-inteligencia-temo/.

#usmexicoborder #border #borderlands #mexicanborder #lafrontera #zonafronteriza #nogales #ambosnogales #battleofambosnogales #battleofnogales #batalladenogales #batalladel27deagosto #gestaheroica #gestaheroicadel27deagosto #arizona #sonora #nogalessonora #nogalesarizona #history #historia #borderwall #borderfence #murofronterizo #cercofronterizo