|

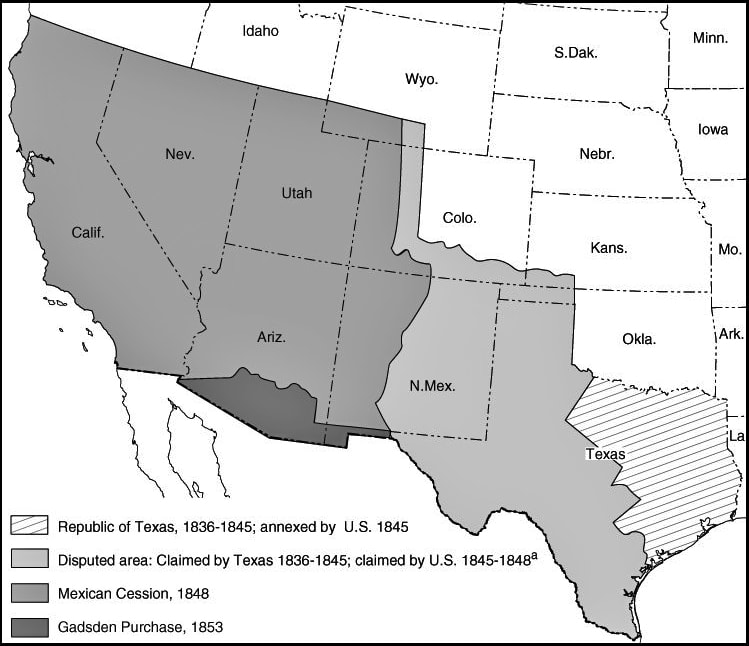

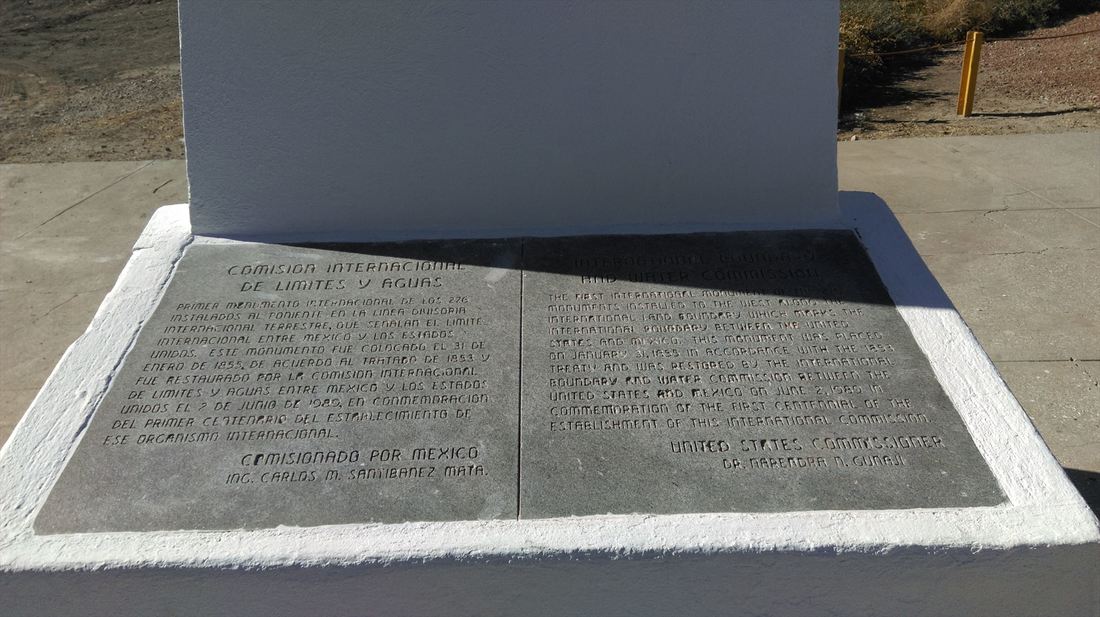

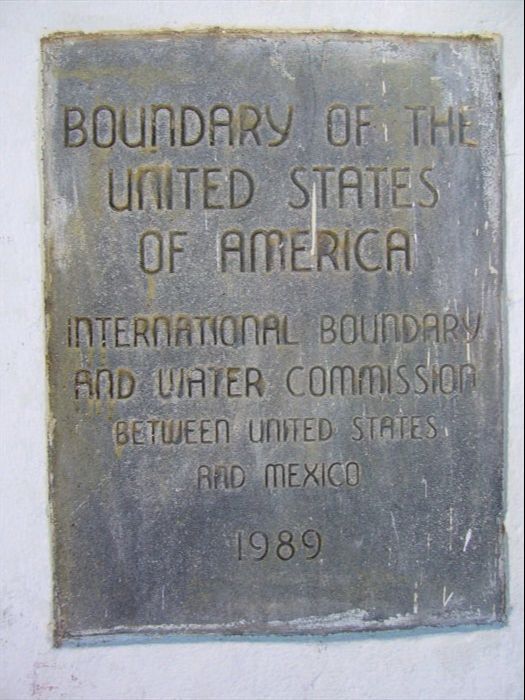

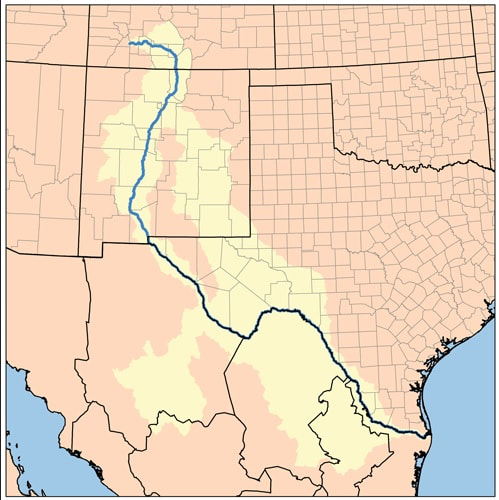

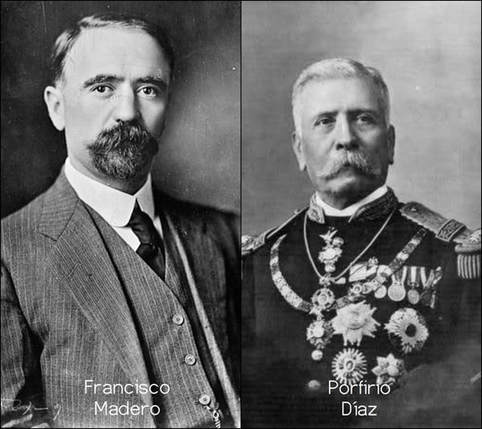

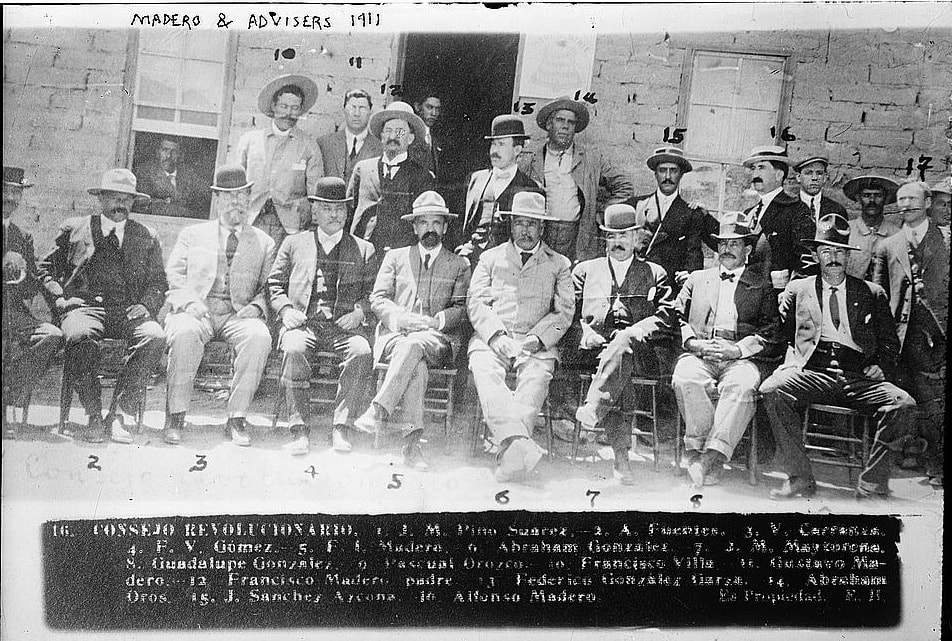

Previously when commemorating the 170th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo we journeyed to the far western corner of the new border that the peace agreement between the U.S. and Mexico created. Surrounded by hills and beach-going crowds on the Mexican side, Boundary Monument 258 marks the U.S.-Mexico border between the corners of Tijuana and San Diego. At 258, it is the highest numbered boundary marker along the land portion of the U.S.-Mexico border which begins with Boundary Monument 1, located 700 miles to the east just outside of Ciudad Juárez-El Paso. Unlike the busy, tightly-controlled scene at Playas de Tijuana/Friendship Park, Boundary Monument 1 is in a hidden canyon along the Rio Grande and without major fence barriers. If, as some border artists have asserted, boundaries are scars on the Earth [1], this is where the wound across the desert begins. Under the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the U.S.-Mexico border begins at the mouth of the Rio Grande (Bravo del Norte) in the Gulf of Mexico, following the course of the river in a northwestern direction for 1,225 miles (2,020 kilometers) until reaching the “southern boundary of New Mexico” [2]. From there, the land border went west across two deserts until it reached the Pacific Ocean. Confusion surrounded the exact location of where the southern boundary of New Mexico was supposed to be until the U.S. pressured Mexico to sell more of its national territory in 1853 (or face the threat of another U.S. military invasion). The Gadsden Purchase (or as it is known in Mexico, the “sale of La Mesilla”) once again resulted in U.S. territorial expansion at northern Mexico’s loss, which enabled the construction of a transcontinental railroad in the 1870s linking Southern California with Texas and the U.S. South. The Gadsden Purchase (“Sale of La Mesilla”) moved the southern boundary of New Mexico to latitude 31° 47”, running westward from the Rio Grande towards the Colorado River. If it was not for this treaty, the current U.S. cities of Yuma, Casa Grande, Tucson, Nogales, Sierra Vista, Mesilla, and part of Las Cruces would have been in the Mexican states of Sonora and Chihuahua. Prior to 1853, the Mesilla Valley was one of northern Chihuahua’s most fertile agricultural valleys, only recently settled primarily by refugees who left New Mexico after the 1848 U.S. conquest. A binational survey team (led by Major William Emory for the U.S. and José Salazar y Larregui for Mexico) met to map the modified border created by the Gadsden Purchase and determined on January 12, 1855, that the southern border of New Mexico began at this spot just outside of what is now Juárez-El Paso, at latitude 31° 47”. The original boundary marker there was built on January 31, 1855 [3]. Constructed atop the site of the original 1855 marker, Boundary Monument 1 (1894) has been given a touch-up by the International Boundary and Water Commission several times, including work in 1966 which gave the monument a stronger concrete base. In 1989 the demarcation text was re-inscribed [4]. The demarcation text on opposite-facing sides of Boundary Monument 1. Near Boundary Monument 1, a smaller marker commemorates the monument’s historic and engineering value. In 1976 the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) proclaimed the border marker as a “National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark.” ASCE rededicated its historical marker in 2015 after years of neglect and vandalism. Between 1891-1894 the United States-Mexican International Boundary Survey (sometimes known as the Barlow-Blanco Survey) re-mapped the border and created new boundary markers all along the line, forcing it to renumber the marker system. In 1894 the eastern terminus marker was thus renumbered Boundary Monument 1, with numbers increasing as one moves westward [5]. Looking south into Texas and Chihuahua from the bank of the Rio Grande in New Mexico. The Rio Grande, which up until now has journeyed southward entirely within the U.S. from the Rocky Mountains, quietly flows along and from this point on becomes the international border between Texas and four Mexican states (Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo Leon, and Tamaulipas). Besides indicating the boundary of the two countries, Boundary Monument 1 also marks the meeting place of Texas, New Mexico, and Chihuahua. The monument’s location (just beyond the trees on the right) is isolated, being away from the centers of both El Paso and Juárez. Access from the U.S. is only available via a 2-mile dirt road (Brickland Road) surrounded by the Rio Grande on one side and steep canyon walls on the other and which begins at a nondescript turnoff in Sunland Park, New Mexico. Although no border walls currently separate this particular portion of the border, one senses great tension while driving across the lonely, winding dirt road to Boundary Monument 1. As part of the road runs through private property (American Eagle Brick Company), access is sometimes not possible [7]. From the Mexican side, the Casa de Adobe is in Juárez's Colonia Ladrillera at the end of Calle Canutillo. Despite the high tension on the U.S. side, it’s not unusual to spot juarenses enjoying a picnic at the Casa de Adobe or wading along the Rio Grande. The green sign in the foreground indicates the actual location of the international border per the calculations of the International Boundary and Water Commission. The adobe structure in the back is a recreation of an historic structure which played a key role in one of the first battles of the Mexican Revolution. Revolutionary leader Francisco Madero organized his forces (including General Francisco Villa) from a similar-looking adobe building which once stood at this site before the May 1911 Battle of Ciudad Juárez which resulted in the Mexican Army’s defeat. The loss of Ciudad Juárez led to the resignation of long-time Mexican President Porfirio Díaz. In early 1911, before the Battle of Ciudad Juárez, Francisco Madero gathered his supporters at the Casa de Adobe to plan strategy together. Madero, seated in the middle (labeled “5”), was joined by Francisco “Pancho” Villa (“10”) and Venustiano Carranza (“3”) among others. This image is one of the most famous from the early Mexican Revolution [8]. Despite its historic value, Madero's adobe headquarters were later demolished and lost to history. The centennial of the Mexican Revolution, and of the Battle of Ciudad Juárez, raised interest among juarenses to commemorate the northern border town’s important contribution to Mexican history. In 2011, the Ciudad Juárez municipal cultural affairs office rebuilt the site using adobe, officially naming it La Casa de Adobe y Monumento a Francisco I. Madero. The site has a small exhibit and monument focusing on this important historical episode as well as the colonial Spanish history of Ciudad Juárez which, from its founding in 1659 until 1888, was known as Paso del Norte [9]. The embedded YouTube video above shows the construction work on the rebuilt Casa de Adobe. Unlike the militarized security apparatus around Tijuana-San Diego’s Boundary Monument 258 (which is currently inaccessible from the U.S. side), there are not fences at the eastern terminus of the land border. Large rocks prevent vehicles from crossing the imaginary line while the watchful eyes of nearby Border Patrol agents (not to mention cameras and security sensors) carefully guard this isolated canyon which is accessible only by dirt roads on either side of the boundary. The Mexico-U.S. land border, barely distinguishable here as a diagonal line only indicated by the metal yellow post and chain, departs from Boundary Monument 1, heading westward across the Chihuahuan and Sonoran Deserts to the Pacific Ocean. Fences and barrier walls mark the border just east and west of here. This isolated canyon scene evokes the invented, but ever real character of the border across the desert. Categories All Sources:[1] Antonio Navalón, “La tercera nación,” Revista de la Universidad de México, no. 27 (2006) 32-36 (http://www.revistadelauniversidad.unam.mx/2706/pdfs/32_36.pdf)

[2] "Transcript of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848)," Our Documents (https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=26&page=transcript) [3] Michael Dear, "Monuments, Manifest Destiny and Mexico," Prologue Magazine, U.S. National Archives, Vol. 37, no. 2, Summer 2005 (https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2005/summer/mexico-1.html) [4] Tygress, “International Boundary Marker No. 1, El Paso, TX,“ Engineering Landmarks on Waymarking.com (http://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WMKNPW_International_Boundary_Marker_No_1_El_Paso_TX) [5] Michael Dear, "Monuments, Manifest Destiny and Mexico, Part 2." Prologue Magazine, U.S. National Archives, Vol. 37, no. 2, Summer 2005 (https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2005/summer/mexico-2.html) [6] "Rio Grande Watershed," New World Encyclopedia (http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/File:Riogrande_watershed.png) [7] Julio-Cesar Chavez, "Access to Border Monument Sometimes Denied by Private Property Owners," KVIA Channel 7, El Paso-Las Cruces, July 21, 2017 (http://www.kvia.com/news/border/access-to-border-monument-sometimes-denied-by-private-property-owners/591021715) [8] "Francisco Madero and his Advisors (1911)," U.S. Library of Congress (http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/mexican-revolution-and-the-united-states/rise-of-madero.html#obj015) [9] Martín Coronado, “Atrae a cientos la Casa de Adobe,” El Diario de Juárez, 9 de abril 2015 (http://diario.mx/Local/2015-04-09_7bc553c8/atrae-a-cientos-la-casa-de-adobe/)

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Carlos Parra

U.S.-Mexican, Latino, and Border Historian Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed