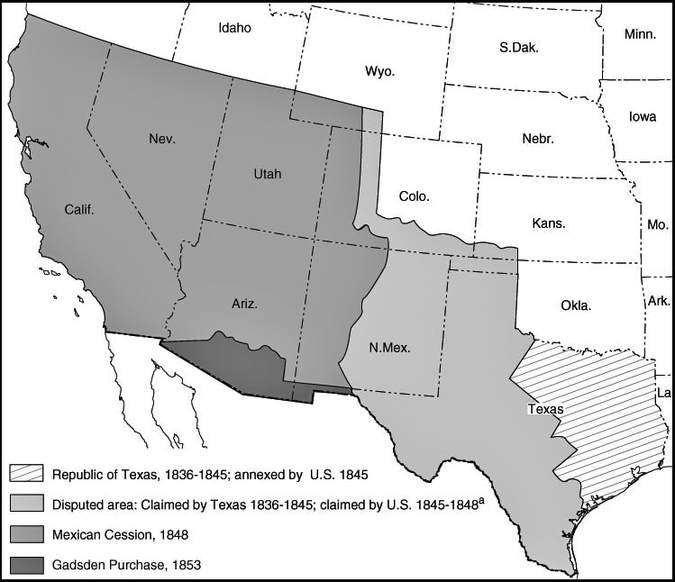

A rare photograph from 1848 depicts the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe and its surrounding environment in the town of Guadalupe Hidalgo as it appeared when the famous treaty between Mexico and U.S. was signed here on February 2, 1848. According to historian Richard Griswold del Castillo, the treaty was most likely signed in one of the (since demolished) buildings to the left of Mexico's most sacred Catholic shrine, the site of the appearance of the Virgen of Guadalupe to St. Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin. After the treaty was signed, the U.S. and Mexican representatives held a mass at the historic Basilica. [3]  An aerial shot of the Basilica de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe and its environs as it appears today. The original historic church [center] was opened in 1709 on the site of two older churches that occupied the sacred space after the 1531 apparitions of Our Lady of Guadalupe to St. Juan Diego. The green-roofed, circular modern Basilica was built between 1974-1976 by architect Pedro Ramírez Vázquez. To the right of the old basilica is the Capuchin Nun's Church and the Capilla del Cerro. IMAGE SOURCE: https://www.sophiatours.com.sv/uploads/image/A_Basilica.jpg While the world has changed much in the 170 years since U.S. negotiator Nicholas Trist and Mexican representatives Luis G. Cuevas, Bernardo Couto and Miguel Atristain signed the treaty – and indeed the town of Guadalupe Hidalgo now another neighborhood of Mexico City known simply as the Villa de Guadalupe – the consequences of the treaty between the two countries remain with us amid debates over Mexican/Latin American immigration and border security enforcement. In this short photo essay, we will briefly explore the far western terminus of the U.S.-Mexican border at the “division line between Upper and Lower California" at the Pacific Ocean” - known as the "Initial Point of Boundary" between Mexico and the U.S. - to consider a small piece of the modern impact of the boundaries created by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on February 2, 1848. Article V of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo cemented the U.S. conquest of the former Mexican far north that would eventually become the U.S. states of California, Nevada, Utah, most of New Mexico and Arizona, and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, and Wyoming. The Treaty's Article V laid out the path of the new, much more southernly boundary between Mexico and United States: “The boundary line between the two Republics shall commence in the Gulf of Mexico, three leagues from land, opposite the mouth of the Rio Grande, otherwise called Rio Bravo del Norte, or Opposite the mouth of its deepest branch, if it should have more than one branch emptying directly into the sea; from thence up the middle of that river, following the deepest channel, where it has more than one, to the point where it strikes the southern boundary of New Mexico; thence, westwardly, along the whole southern boundary of New Mexico (which runs north of the town called Paso[ [today's Ciudad Juarez]) to its western termination; thence, northward, along the western line of New Mexico, until it intersects the first branch of the river Gila; (or if it should not intersect any branch of that river, then to the point on the said line nearest to such branch, and thence in a direct line to the same); thence down the middle of the said branch and of the said river, until it empties into the Rio Colorado; thence across the Rio Colorado, following the division line between Upper and Lower California, to the Pacific Ocean.”  With the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo the Mexican Republic turned over vast lands in what is now the U.S. Southwest to its northern neighbor in the "Mexican Cession." Mexico's territorial losses in the war also included an area indicated in this map in a lighter grey that Texas claimed when it was an independent nation. In reality the Texans did not govern those lands (which stretched all the way up to modern northern Colorado), being controlled by Native American peoples as well as Mexican communities in northern and eastern New Mexico. SOURCE: https://www.ssc.wisc.edu/soc/racepoliticsjustice/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/treaty_guadalupe_hidalgo_map.jpg Depending on one's perspective, the U.S.-Mexican boundary either begins or ends at the Pacific Ocean. When boundary surveyors for both countries began mapping out the actual border in 1849 after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was ratified, the initial survey began here at the Pacific coast. Boundary markers soon went up. The first boundary marker raised at this border area was dedicated on July 14, 1851 as Boundary Monument 1. This "Initial Point of Boundary" was renumbered Boundary Monument 258 in 1894 when it was replaced by the current marble marker put up by a binational border survey known as the Barlow-Blanco Commission. As can be seen in this image looking north from Playas de Tijuana, and reflected in testimonies of people who lived in the area in the 1800s, there was a border but at the same time there also wasn't a border. Border fences here would not come until later, after fences went up in Nogales, AZ, in 1918 and Calexico, CA, and Douglas, AZ, in 1919. [4] ABOVE: Boundary Monument 258 as it looked like in a less militarized border in the increasingly distant year of 1973 when the International Boundary and Water Commission photographed Boundary Monument 258 for its inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places (SOURCE, National Park Gallery Digital Asset Management System [5]). BELOW: The modern border fencing has left the monument - and a few feet of U.S. territory - entirely on the Mexican side. Located at the far southwestern corner of the U.S. – and also the far northwestern corner of Mexico – Friendship Park was dedicated by U.S. First Lady Patty Nixon on August 18, 1971, in a ceremony in which she praised the relationship between the two countries. Seeing the large crowd of observers across the line in Playas de Tijuana, Nixon walked up to the short barbed wire fence and asked her Secret Service detail to cute the wires and allow her to interact with the tijuanenses. At the end of the event, Mrs. Nixon remarked, “I hope there won't be a fence here too long." [6] A far cry from the post-fence vision Mrs. Nixon had for Friendship Park when she dedicated it in 1971, the meeting place of Friendship Park and Playas de Tijuana seems more like a fortified prison perimeter than the international boundary between supposedly friendly neighbors with deep cultural and economic ties that cross the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo's border. At Friendship Park, two sets of fencing controls the border there. In past years, visitors to Friendship Park (located within California's Border Field State Park) could walk up to the border fence and talk to tijuanenses on the other side of the fence. Now, visitors have only limited hours to communicate with friends and family at the fence on Saturdays and Sundays under the supervision of U.S. Border Patrol agents. Here, a few USBP officers prepare to the close the secure area along Friendship Park's fence. The recently-constructed border barrier separating Playas de Tijuana from Friendship Park was the result of the 2006 Secure Fence Act that included Republican and Democratic lawmakers (including then-Senators Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama) passed into law weeks before the 2006 congressional elections. New steel fencing went up between Tijuana-San Diego and through large swaths of the international boundary the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo created. A binational crowd congregates at Friendship Park across from Tijuana's Plaza de Toros in December 2016. Opponents of the militarization of the border the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo created meet regularly at the border to protest the tension in the U.S.-Mexican relationship. Led by local religious and immigrant rights leaders, "Friends of Friendship Park" brings together many community activists who dream of a world where local transnational communities are not the scapegoats of U.S. politicians detached from the realities and complexities of the border region. The far southwestern corner of the U.S. is heavily controlled and visitors to Friendship Park/Border Field State Park are currently not allowed to the walk up to the fence from the California side. However, Playas de Tijuana on the Mexicna side is much more lax than conditions in the "land of the free" with day visitors congregating all over the beach right up to the fence. Coconuts, chamoy, papitas, beer and drinks mark the experience of tijuanenses visiting the far northwestern corner of Baja California. Looking east from the initial point of boundary between the U.S. and Mexico, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo's border (manifested in physical form by hills and steel fencing) winds eastward on its long journey to the Rio Grande and, eventually, the Gulf of Mexico. Friendship Park's border barrier, again, is a double-fencing infrastructure which includes a paved road for USBP patrol cars, essentially rendering a swath of U.S. parkland and territory as No-Man's Land. The militarized border residents of the Mexican north and U.S. Southwest are familiar with in the 2010s could not have been imagined by the diplomats who negotiated the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in early 1848. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo's legacy - in drawing the first part of the modern U.S.-Mexican boundary - has left a deep impact in countless aspects of life along the two countries. Boundary Monument 258 (formerly 1), Friendship Park, and the border fence between Tijuana and San Diego are significant representations of the actual border that was first traced out on paper in a building across from the historic Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in the town formerly known as Guadalupe Hidalgo on February 2, 1848. We will continue to examine this legacy in future NOMADIC BORDER journeys. NOTES

[1] "Border Fence Blocks Access to Important Historical Site," San Diego City Beat, December 21, 2011 (http://sdcitybeat.com/culture/seen-local/border-fence-blocks-access-important-historical-site/) [2] Griswold del Castillo, Richard. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: A Legacy of Conflict. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1992. [3] Griswold del Castillo, The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, pg. 38-42. [4] "Border Field State Park," Schoenherr Home Page in Sunny Chula Vista, (http://sunnycv.com/southbay/exhibits/borderfield.html) [5] "Initial Point of Boundary Between U.S. and Mexico," National Register Information System (https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/NRIS/74000550) [6] Nevins, Joseph. "Pat Nixon at the U.S.-Mexico Border," Los Angeles Indymedia, August 27, 2008, (http://la.indymedia.org/news/2008/08/219918.php)

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Carlos Parra

U.S.-Mexican, Latino, and Border Historian Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed