|

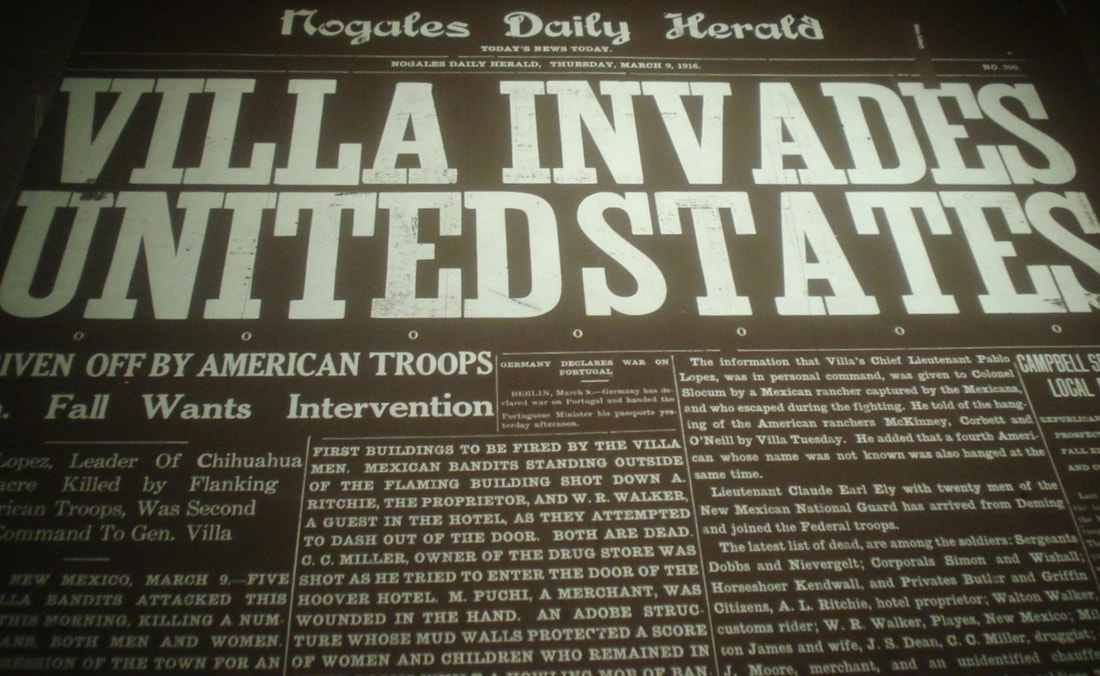

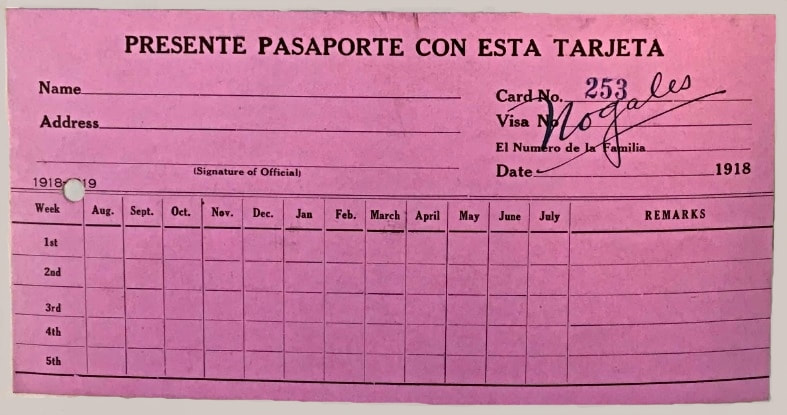

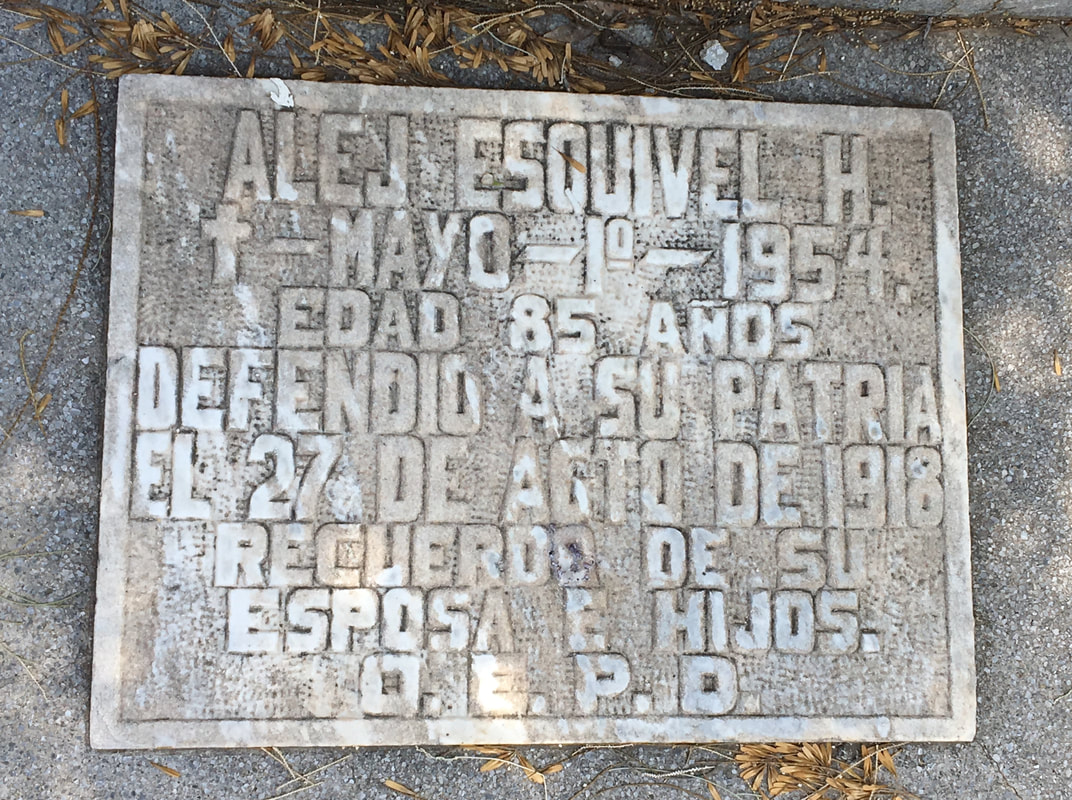

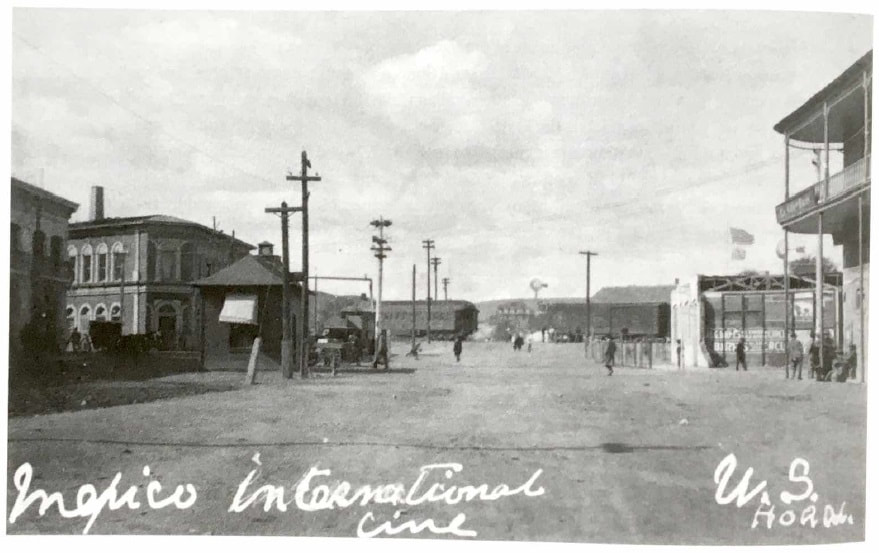

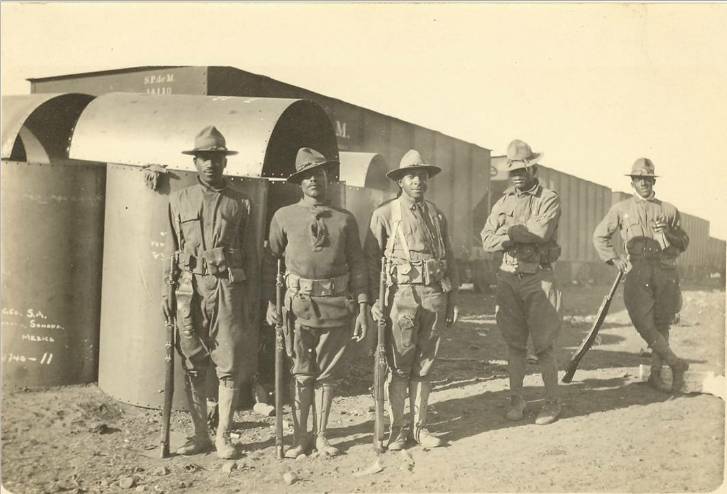

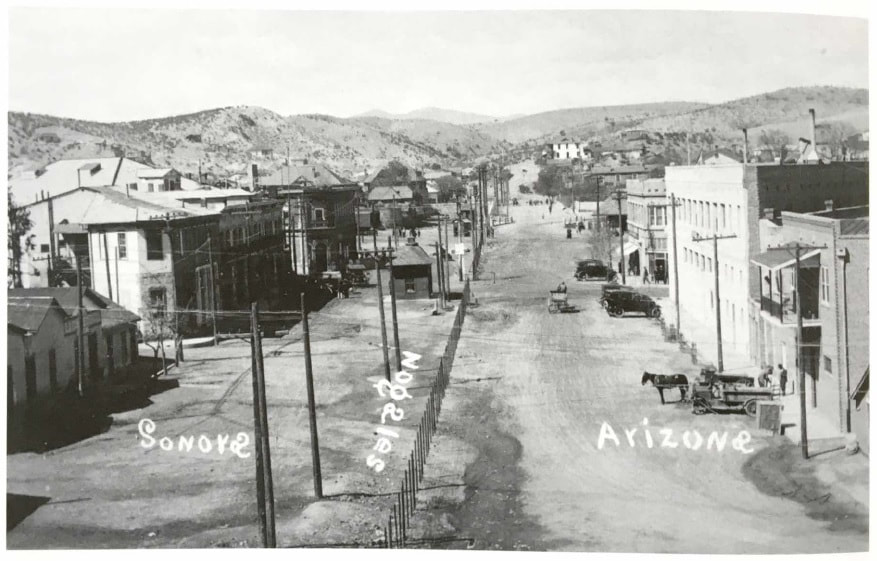

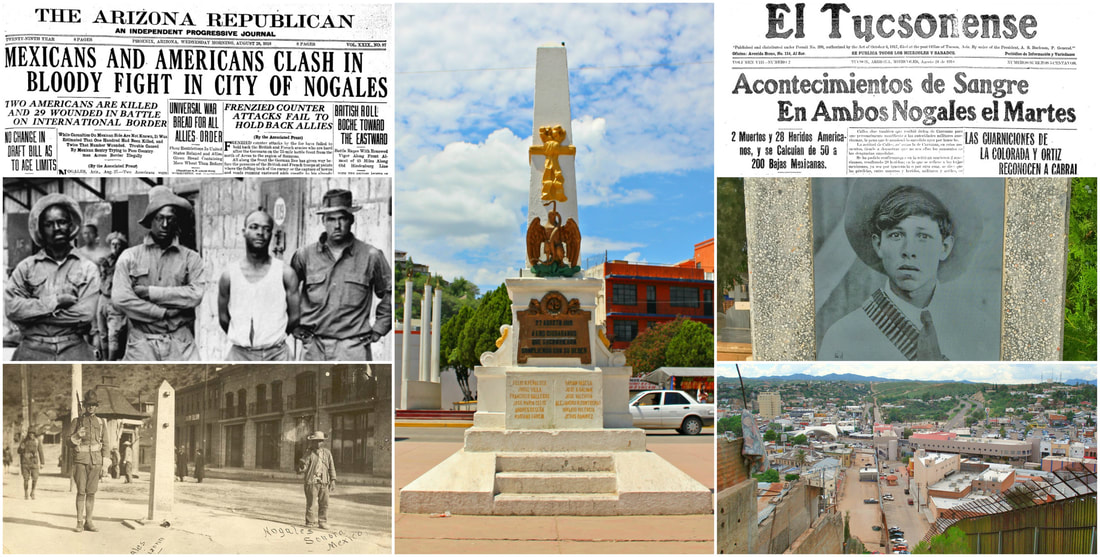

A version of this photo essay appeared as an article in the August 24, 2018, edition of the Nogales International; special thanks to editor Jonathan Clark for allowing me to contribute to the local paper's coverage of the battle's centennial A century ago on Aug. 27, 1918, Mexicans and Americans fought one another at the Battle of Ambos Nogales, leaving as many as 129 Mexicans and four Americans dead, and approximately 330 wounded. There was another toll as well: the previously open border between Nogales, Ariz. and Nogales, Sonora. As a result of the battle, the two Nogaleses became the first cities on the U.S.-Mexico border to be divided by permanent border fences. Wartime tensionBeginning in 1910, the Mexican Revolution engulfed the region as different factions fought for control of cities like Nogales, Sonora and their access to U.S. trade. In 1913 and 1915, competing Mexican armies battled for control of the city. Violence sometimes spilled into the United States, leading to the deployment of hundreds of U.S. troops to the border.  General Francisco Villa was one of the main military and political leaders of the Mexican Revolution who fought for control of the government against rival factions. At one point the U.S. Government favored Villa taking over Mexico, but by early 1916 Villa's movement was mostly over. In revenge for the U.S. turning away from him, Villa invaded Columbus, New Mexico, on March 9, 1916 (as reported on by the "Nogales Daily Herald"), leading to a U.S. invasion of Chihuahua that year. Thousands of U.S. soldiers and National Guardsmen were deployed to Nogales and other border cities as a result of these tensions. The U.S. never caught Villa. The open border began to close as U.S. participation in World War I led to the new requirement that all citizens and foreigners have passports to enter and leave the country. Mexicans who crossed the border daily for work suffered greatly from constantly changing passport rules.  An example of the "food cards" border crossers from Nogales, Sonora, and elsewhere along the borderlands were required to present with their passports in summer 1918. The spaces with dates allowed U.S. border inspectors to track and limit the number of times Mexican people crossed the border to buy food. (Courtesy, National Archives and Records Administration) The United States also sought to protect wartime food supplies by limiting the number of times Mexicans with passports could cross the line. By August 1918, the U.S. Consulate distributed “food cards” to people in Nogales, Sonora who wished to cross the border to buy foodstuffs for their families. Despite a severe food shortage in northern Mexico, the U.S. government limited the crossings of Mexican grocery shoppers to once per week. Meanwhile, tensions between Mexicans and U.S. border troops in Nogales festered. In addition to an Aug. 14, 1915, riot between U.S. soldiers and Mexicans, U.S. troops shot and killed two Mexican nationals on the Nogales border on Dec. 31, 1917 and March 22, 1918.  A Nogales, Sonora, mural of José Antonio Elena Rodríguez, a 16 year-old who was shot multiple times by a U.S. Border Patrol Agent on October 10, 2012. Although multiple claims surround José's killing, the youth was killed while entirely in Mexican territory only yards from the border. The killing of Mexican nationals by U.S. border security officials happened before the Battle of Ambos Nogales and continues in the 21st Century. A Nogales, Sonora, mural of José Antonio Elena Rodríguez, a 16 year-old who was shot multiple times by a U.S. Border Patrol Agent on October 10, 2012. Although multiple claims surround José's killing, the youth was killed while entirely in Mexican territory only yards from the border. The killing of Mexican nationals by U.S. border security officials happened before the Battle of Ambos Nogales and continues in the 21st Century. A third fatality was almost added in June 1918 when a U.S. soldier shot at a Mexican man named Ygnacio Orozco after a miscommunication at the unfenced border. Félix Peñaloza, mayor of Nogales, Sonora, defended Orozco and installed a short fence a few yards long on Calle Internacional as a response. Peñaloza hoped better indicating the border and controlling the movement of both U.S. and Mexican foot traffic with a fence would prevent further shootings. Ambos Nogales was on the verge of exploding. The battleThe battle began at 4:10 p.m. on Aug. 27, 1918, when carpenter Zeferefino Gil Lamadrid walked from Arizona towards the border. Gil Lamadrid, a Mexican national, carried unidentified contraband on his person and tried to evade an outgoing inspection. Mexican customs inspectors told him to keep walking as U.S. Customs Officer Arthur Barber pulled his revolver and ordered him to return. Although U.S. and Mexican sources differ, it appears that Mexican customs inspector Francisco Gallego shot and wounded U.S. Army Private William Klint when he pointed his rifle at Gil Lamadrid. The shootout expanded as nearby U.S. troops exchanged gunfire with Gallegos and the other Mexican guards while Gil Lamadrid escaped. As the sound of gunfire echoed, dozens of Mexicans joined the fight, firing from behind buildings and sniping at U.S. troops from the surrounding hills. Histories of the battle based on second-hand accounts claim the Mexican combatants were soldiers acting under the direction of German spies, but no evidence to corroborate this exists at the Pimeria Alta Historical Society, the Archivo Municipal de Nogales or the U.S. National Archives. The majority of the Mexican Army in Nogales left days before to fight rebels near Sasabe, and so the combatants were mostly working-class civilians acting without orders.  Alejandro Esquivel was one of many Mexican civilian combatants who fought against the U.S. during the Battle of Ambos Nogales and died much later at age 85. Even then, his gravesite epitaph honored Esquivel (who had a female relative who died in the battle) as having "defended his country on Aug. 27th, 1918." Their motive seems to have been anger at local border conditions. As an example, four combatants barged into the U.S. Consulate and allowed all the staff to escape, except a clerk known to harass Mexicans when he worked as a customs agent. Elmer Cooley was shot in the thigh during the ordeal, but was not treated as a hero. U.S. Consul Ezra Lawton acknowledged Cooley’s history and fired him after the battle. The U.S. Army’s 10th Cavalry Regiment, a segregated African American unit, raced to combat. Although so-called “Buffalo Soldiers” like Sgt. James Penny were not allowed into some Nogales, Ariz. restaurants, they fulfilled their duty. Capt. Joseph Hungerford, a white 10th Cavalry officer, died leading a charge up the hill east of Morley Avenue to stop the sniper fire. Several cavalrymen were wounded, but the position was taken.

Several Mexican women, two of whom were wounded, braved U.S. fire to rescue the injured. According to the Corrido de Nogales, they said: “No hay cuidado, somos puras mexicanas,” or “No worries, we’re pure Mexican women.” After terse truce talks, a white flag was raised over the Mexican customs house at 5:45 p.m., but gunfire from the Sonoran side didn’t end until 7 p.m. The U.S. Army closed the border until the afternoon of Aug. 28, leaving hundreds of Mexican workers stranded in Arizona, with many being forced to sleep on park benches overnight. As dozens of funeral processions took place over the next two days, Sonoran Gov. (and future Mexican President) Plutarco Elías Calles and U.S. Gen. DeRosey Cabell met on International Street to discuss the conflict. Both regretted the violence and Calles, seeking to maintain his government’s relationship with the United States, dismissed the Mexican civilian combatants as “irresponsible.” The fenceHoping to avoid another battle, Calles and Cabell found a solution that has defined Nogales ever since: a border fence. The two-mile-long, six-foot-tall barbed wire fence Calles and Cabell discussed was installed that fall at a cost of $5,000 ($80,250 in 2018) and marked the first time a permanent fence separated two cities on the U.S.-Mexico border. (The barrier installed by Peñaloza and an earlier fence between Ambos Nogales that stood August-November 1915 were temporary). The 1918 Nogales border war created a fence trend that other cities like Douglas, Naco and Calexico followed. The Battle of Ambos Nogales has been largely forgotten on the U.S. side. But in Heroica Nogales, Sonora, renamed as such by the Mexican Congress in 1961, memory of the actions of Félix Peñaloza and the local citizenry live on. Dedicated in 1921 by Felix Penaloza's widow Paulita, the Monumento a los Heroes is one of the most prominent reminders of the fallen Nogales, Sonora, defenders from August 27, 1918. The monument, however, makes no mention of the at least 2 women killed in the battle (Maria Esquivel and Adela Valdez, both of whom are buried in the Panteon de los Heroes and are indicated as having died during the Nogales border war).  Dignitaries from Mexico and the U.S. met at the Felix Penaloza Memorial to celebrate the battle's centennial on August 27, 2018. The younger man in the grey jacket is Heroica Nogales, Sonora Municipal President (Mayor) Cuauhtemoc "Temo" Galindo. Beside Mr. Galindo are Nogales, AZ, Mayor John Doyle (on his right); Virginia Staab, U.S. Consul General in Nogales, MX; Ricardo Santana Velazquez, MX Consul General in Nogales, AZ [2].  LEFT TO RIGHT: Nogales, AZ, Mayor John Doyle, Nogales, SON, Mayor Cuauhtemoc "Temo" Galindo and his mother at Felix Penaloza's tomb on August 27, 2018. Although political debates about the border often divide the U.S. and Mexico, local leaders in Nogales and elsewhere along the border region have deep binational ties that cut across nations and languages [3].  Bus service in the southern parts of Heroica Nogales are provided by a bus drivers' organization named after the "Heroes of August 27th." Although many area residents are not aware of the specific details of the battle, the events of August 27, 1918, are very present in local Nogales culture and lore.

Even so, the role of the Battle of Ambos Nogales of Aug. 27, 1918 in the origin of border fencing is less recognized. For more on this critical moment in the formation of the U.S.-Mexican border, please explore our website's detailed revisiting of the real history of the causes and lasting effects of the Battle of Ambos Nogales: The August 27, 1918 Battle of Ambos Nogales and the First U.S.-Mexican Border Fences - Part 1 (detailing the origins and outbreak of the Nogales border war) The August 27, 1918 Battle of Ambos Nogales and the First U.S.-Mexican Border Fences - Part 2 (detailing the consequences and memories of the 1918 border violence in Nogales) NOTES:[1] "Buffalo Soldiers in Arizona," Sonoran Jackrabbit, The Graveyard Rabbit of Southern Arizona (April 14, 2010), (http://sonoranjackrabbit.blogspot.com/2010/04/buffalo-soldiers-in-arizona.html)

[2] TemoGalindo Twitter, Aug. 27, 2018 (https://twitter.com/TemoGalindo/status/1034129373203492865) [3] TemoGalindo Twitter, Aug. 27, 2018 (https://twitter.com/TemoGalindo/status/1034137888106131456)

4 Comments

Ramón Villarreal

8/27/2020 13:22:51

Very informative!

Reply

Trish Anderson

8/27/2020 18:47:50

This was great-not too long but filled with information I never knew. I especially liked the pictures and captions. Thank you for sharing this!

Reply

9/1/2020 01:45:37

Trish, thank you for your encouragement! I wanted this piece to be a condensed version of the more detailed longer examination of the Battle of Ambos Nogales. There's so much to say about this part of Nogales and US-Mexican border history.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Carlos Parra

U.S.-Mexican, Latino, and Border Historian Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed