|

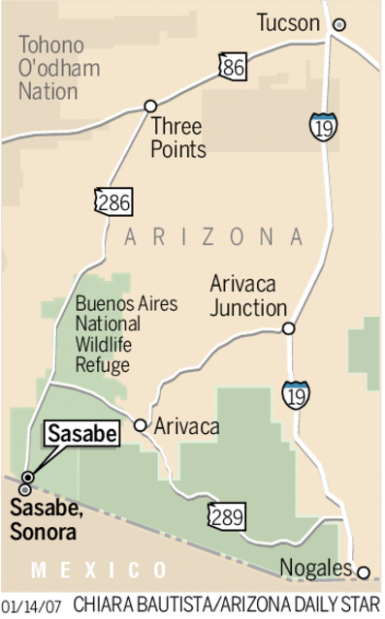

Our tour of the Altar Valley picks up at the U.S.-Mexico border crossing at Sásabe, Sonora and Sasabe, Arizona. As already mentioned, in the 2000s and early 2010s the Altar Valley corridor was the principal entry way for undocumented immigrants headed into the United States. The Altar Valley is named after the town and river of the same name in Sonora. On the northern side of the international boundary the Altar Valley – which runs from the border to the extreme western suburbs of Tucson – has few population centers. In Arizona, the Altar Valley is primarily oriented north-to-south and surrounded by the Baboquivari Mountains to the west and the Sierrita, Cerro Colorado, Las Guijas and San Luis Mountains to the east. The smuggling of people and contraband in this narrow valley greatly concerns many local and national U.S. residents. The 2016 election of Donald Trump as U.S. President occurred in the context of rising nationalism in the U.S. as well as the candidate’s controversial proposal to build a wall along the entire U.S.-Mexican border. The first steps toward carrying out that project were undertaken in 2017, but in the Altar Valley – as in the majority of the border – there already are border fences and walls. The existing border fence which can be seen in this image looking west from Sasabe was built in 2007 by the Phoenix, Arizona-based Sundt Construction Company. This earlier barrier’s installation caused much controversy not only because of its social implications but also for its negative environmental impact on area wildlife. [1]  The U.S. Customs House in Sasabe, Arizona just after its 1937 construction. The colonial revival brick building – a rare type of government architecture in the border region – was built as part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal program. (SOURCE: Living New Deal, https://livingnewdeal.org/projects/inspection-station-former-sasabe-az/) On the U.S. side, Sasabe, Arizona is a ghost town-like border community. The Sasabe Port of Entry is the least transited border crossing in Arizona. According to the Arizona-Mexico Commission, a non-profit group dedicated to the economic development of Arizona’s border with Mexico, the U.S. Port of Entry at Sasabe only registered an average of 165 vehicles, trucks, and pedestrians per day in 2011, with a total 33,980 crossings for the whole year. In comparison, the 3 ports of entry in Nogales (Arizona’s busiest port of entry) registered 9.5 million crossings in 2011; in a typical day it is not unusual for the Mariposa Port of Entry to register at least 600 northbound cargo trucks before 4pm. However, in Sasabe vehicle traffic is so light one must press a button when crossing into the U.S. in order for customs officials to step out from their office and inspect one’s vehicle. The brick colonial revival building in Sasabe dates back to 1937 and is included in the National Register of Historic Places. [2]  Sasabe, Arizona Port of Entry by Johnny Milano. In 1992-1993 the U.S. government modernized the port, adding truck and secondary inspection infrastructure among other things. Customs officers at this port typically remain here for many years and are well known in the local community (SOURCE: Daily Mail, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3258980/What-guarding-border-really-looks-like-Pictures-veterans-retired-private-security-experts-patrol-Mexico-border-stopping-immigrants-smugglers-human-traffickers.html) Like the Sásabe in Sonora, the name of the Arizonan Sasabe comes from the O’odham place name for the area, (Ṣaṣawk) “head valley.” Today the O’odham live just northwest of Sasabe in the Tohono O’odham Reservation, but their legacy lives on this valley and many cross this border to visit their families in the Mexican side. The indigenous inhabitants of the Altar Valley encountered Catholic missionaries in the service of the Spanish Crown after the end of the 17th Century when Jesuit priests arrived here. According to the owners of the Rancho de la Osa located a few miles west of Sasabe, the oldest European-built structure in Arizona is on that ranch and dates back to 1725 when Jesuit missionaries built a small adobe structure to store goods in transit between the Rio Altar missions (like the one at Oquitoa) and the missions along the Santa Cruz River. The structure was abandoned during the 19th Century when the Spanish priests at the missions in what are now Sonora and Arizona were expelled by the Mexican Government. Today the historic 300-year-old adobe storehouse functions as a cantina for the guests at the Rancho de la Osa which itself was established in 1889 by William Sturges. [3] The northern half of the Altar Valley became a part of the United States after the 1853 Gadsden Purchase (Venta de la Mesilla) when Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna, under intense U.S. pressure, sold what is now southern Arizona to the U.S., dividing the valley in two. Archeological investigations indicate that semi-sedentary O’odham groups lived throughout different parts of the valley during the 18th and 19th Centuries. What we now know of as Sasabe, Arizona, has its roots in 1912 when Carlos Escalante and Fernando Serrano, along with their families, fled the violence of the Mexican Revolution of the 1910s. Escalante kept moving north, but Serrano and his family decided to stay on the border and built an adobe home in what at the time were unowned open lands. Fernando Serrano named the area in honor of his saint, St. Ferdinand or San Fernando, building a small chapel dedicated to him on a hill near the international boundary. The Serrano family built more adobe homes for the travelers who transited the corridor between Tucson and the silver and gold mines in Mexico, giving the border crossing a more established character. [4] Although an 1880 federal decree called for the establishment of a Mexican customs house at El Sásabe, Sonora, the small town grew slowly and it was not until the 1910s that a permanent building was constructed for the customs house which had been housed in a tent before then. The Serrano family’s income grew as they rented homes for area residents, including the U.S. customs officials from the local border post. According to the Serrano’s descendants, the growth of San Fernando, Arizona encouraged the development of El Sásabe, Sonora (sometimes known historically as Mesquite) which entered into a certain level of prosperity in the 1920s when the Prohibition of alcohol in the United States promoted the existence of bars and gambling houses in that Mexican border town which reached a population of 800 in that time. [5] The Serrano and Escalante families maintained contact after immigrating to the U.S. – by 1917 Carlos Escalante and his family decided to reunite with their friends in San Fernando. Little by little, the Serranos sold their properties to Escalante who eventually became the owner of the border town, earning the title of “King of Sasabe” in the process. The scarcity of publically-accessible documents related to the history of Sasabe makes it difficult to determine the date in which it took on its current name – many historic maps identify the location as San Fernando, including a 1935 map from the Arizona State Highway Department. However, by 1941 the community assumed the name “Sasabe” again according to a U.S. Geological Survey map that year. [6] A school research project by Lilia Urias (a young teen in 7th Grade at the San Fernando Elementary School) published in the February 21, 1941, edition of the Tucson Daily Citizen provides us with information that can help us determine when the name change happened. Young Lilia’s research cites her interview with the town’s postmistress, Winifred Hickcox, who informed her that the border town changed its name because much of the mail headed to the area’s residents was mistakenly sent to the much larger city of San Fernando north of Los Angeles. Sasabe likely returned to its historic O’odham place name in the winter of 1940-1941 when the post office there was transferred from the Rancho la Osa to its current location in an adobe which was at the time another property owned by Carlos Escalante, the “King of Sasabe.” [7]  The corridor where the Puerto Lobos-Sasabe railroad in the northwest of Sonora would have been built in the 19th or early 20th centuries. Linking Sasabe and the surrounding mining area with Puerto Lobos and Puerto Libertad on the Gulf of California might have completely changed this area’s history. (SOURCE: Luigi Radelli y Efren Perez Segura, “The Gold Placer of El Boludo Northern Sonora, Mexico,” Boletin Depto. De Geologia, UNI-SON, vol. 9, no. 1) The history of Ambos Sasabes and the entire Altar Valley might have been very different if a railroad project promoted by the Mexican government since the 1880s had been built. Inspired by the presence of various silver and gold mines in the Mexican portion of the Altar Valley, U.S. investors and the Mexican government wanted to build a railroad between Puerto Lobos on the Gulf of California and Sasabe, Arizona to better develop the mines. The first railway concession was given in 1882, but repeated problems with financing delayed construction. By 1910 the Development Company of America, with its headquarters in Sasco, Arizona (a current day ghost town) received a concession from the Mexican government to build the railway to the Gulf, with a route running from Puerto Libertad, Puerto Lobos, and Caborca before reaching Sasabe. The Development Company of America also hoped to connect the line to Sasco in Central Arizona. Severe economic problems within the Development Company and the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution in November 1910 definitively blocked the construction of this railway link between the two countries. [8] The U.S.-Mexican border is often known for its busy border cities. When one thinks of the border crossings at San Diego-Tijuana, El Paso-Ciudad Juárez or Ambos Nogales one might usually think of the high volume of vehicular and pedestrian traffic as well as the presence of stores everywhere. The Ambos Sasabes do not share these characteristics as the Arizonan town is nearly a ghost town. It is difficult to pin down the exact number of residents in remote Sasabe since it does not have an incorporated government and is just a dependency of Pima County. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, only 54 persons lived in the extensive 85633 zip code in which Sasabe is located in. However, a 2011 article by Arizona Republic journalist Daniel González stated Sasabe only had 11 residents. [9] In Mexican and U.S. border cities it is common to see bus or shuttle van stops linking the border crossings with destinations in the interior of each country. Travelers leaving Nogales and headed towards Tucson, for example, can get there by these forms of transportation and can count on departures leaving every half hour or hour. However, here in Sasabe one must have much patience – and access to a cellular phone – to obtain transit to Tucson or Phoenix. The wait for a San Judas Shuttle van occurs in a rough environment outside of an abandoned building. A walk through the only paved street in Sasabe demonstrates what is left over from earlier times in this border town. Many adobe homes here bear witness to the heritage of the ranching community that formerly existed in Sasabe. Many of these homes may have been built with bricks formed at the brickyard in Sásabe, Sonora. Before the demographic decline that affected the Altar Valley and Sasabe with the reduction of the local cattle industry, many of the cowboys from nearby ranches – such as the Aros, De la Osa, Buenos Aires, and Santa Margarita – lived in these homes built and owned by the Serranos and Escalantes. Sonora State Route 43 was one of the most important highways we journeyed through in our Mexican Altar Valley tour, particularly when heading north from Altar, Sonora. In the U.S. side of the valley, Arizona State Route 286 connects the border town of Sasabe with the Tucson metropolitan area (terminating about 20 miles west of Tucson on State Route 86) through a desolate desert corridor. State Route 286 is highly patrolled by the U.S. Border Patrol and figures prominently in the smuggling of people and narcotics. A few steps from State Route 286, valley residents and travelers find one of the few formal businesses in the town – the Sasabe Store. Sasabe’s only store provides some basic services – such as food and fuel – for those who live or travel through this remote setting. Alice Knagge and Deborah Grider (mother and daughter) are the owners and workers of the store which has belonged to their family since 1932. Deborah Grider, a descendant of Carlos Escalante, the “King of Sasabe,” remembers how her childhood in Sasabe was like before the 1960s when there were many families in that Arizona border town. Back then all of the homes in Sasabe were the property of her grandfather Carlos Escalante. Whenever she was not helping her family with the store and other businesses, little Deborah would cross into Mexico to buy candies and was waved through on her way back by U.S. customs guards. Describing the store today in a Google review, Anna Chan – a traveler through Sasabe – wrote that the store carries “a lot of needs and nice to haves - good for those who find themselves stranded somehow, and great for those scattered locals who can't make the trip to shop in Tucson.” [10] Although Sasabe is almost a ghost town, it is not so entirely and the few people who live in this part of the Altar Valley have the option of visiting the “Hilltop Bar” at the center of the border town on weekends. Journalist Daniel González described the site as what “has got to be the strangest, if not the smallest, bar in Arizona. Just 12 stools and a little table big enough for a game of cards.” Located behind the Sasabe Store, the Hilltop Bar is also managed by Grider who has decorated the bar with an eclectic aesthetic mixing cowboy and Native American motifs. According to Google reviewers, Deborah Grider does not permit drunk clients without designated drivers to drive home, instead forcing them to stay in one of the family’s bunks for $25 a night. Individuals with the need to mail out correspondence can also visit the U.S. Post Office next door in its historic adobe from Monday to Friday from 8:30am-10:30am and 11:00am-3:00pm. As we already know from Lilia Urias’s 1941 report, the post office moved to this Escalante adobe during the winter of 1940-1941. [11] All of the homes in Sasabe, Arizona, remained in the hands of Carlos Escalante, the “King of Sasabe”, for many decades until 1959 when he first tried selling all of them. According to various press reports, Sasabe has been one of the few towns in all of the U.S. to be privately owned by a sole family. Sasabe’s sale attracted so much attention that a March 1960 issue of LIFE magazine reported on the event. In 1977 the heirs of the famous King of Sasabe sold all of their properties in the border town to a Mexican real estate company based in Altar and Caborca, Sonora, known as Hermanos Pesqueira, S.A. Even now the little 11-person U.S. border town is still in the possession of the Pesqueira family. [12 The almost overwhelming quiet that dominates Sasabe makes one think that children are far away. In fact, this rural border town has its own Kinder-8th grade school, the San Fernando Elementary School. With only 27 students attending during the 2013-2014 school year, the San Fernando Unified School District #35 is one of the smallest school districts in all of Arizona. During that year, the largest grade cohorts had 4 students; according to the district’s website, San Fernando Elementary has 2 teachers (one for Kinder-4th grade and another 4th-8th grades who also specializes in special education). Counting the two teachers, the total number of personnel for the district is 8. Youth who finish 8th grade at San Fernando Elementary School do not have the option of attending high school in the Sasabe area and must instead attend high school in Sahuarita (65 miles/104km or 80 minutes away) or Tucson (66 miles/106km or 72 minutes away). Deborah Grider, the current proprietor of the Sasabe Store, would travel daily to Sahuarita High School in the 1960s and 1970s in a journey that would take almost 2 hours each way. Sasabe and Altar Valley teens who attend high school in Sahuarita must pick up the bus in front of the Sasabe Store. [13] Heading north from Sasabe one can see a small Catholic chapel off the road, the San Fernando Church. The picturesque church is usually closed. Newspapers from the 1950s and 1960s indicate that both Sasabes struggled to recruit clergy to preach in these remote communities. A few miles west of here is the historic Rancho De la Osa which is famous in the region for being visited by hunters, actors (like John Wayne) and even two U.S. presidents (Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson). A group of investors purchased the ranch when it was auctioned in 2016, reopening it for visitors interested in the Sonoran Desert. Long before it was converted into a guest ranch, the Rancho De la Osa was a great cattle operation so immense that stray cattle was sometimes found in the outskirts of Phoenix in the bygone times before suburban housing developments and highways encroached on the desert. [14] One of the most important properties in the Arizona Altar Valley is the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The wildlife refuge preserves the unique ecosystem of this part of the valley with its grasslands, arroyos, and mesquite/oak tree groves. Before becoming a wildlife refuge, the property was Buenos Aires Ranch which belonged to the Aguirre family, a Mexican family which left a great mark on the U.S.-Mexico border region in the 19th Century. Pedro Aguirre, a descendant of Spanish frontier soldiers in Chihuahua, immigrated with his family to Las Cruces, New Mexico in the 1850s where they formed a ranch and a freight business that eventually served an expansive region from Altar, Sonora to Independence, Missouri. In 1864 his son Pedro Aguirre Jr. established the Buenos Aires Ranch, using it as a base of operations for the family freight business along the Altar-Tucson route while also dedicating himself to cattle-raising. In 1909 Magdalena Aguirre, Pedro Jr.’s widow, sold the Buenos Aires Ranch to their neighbors in the Rancho De la Osa. [15] Over the years the Anglo-American investors who owned the ranches developed their economic potential, making the Buenos Aires Ranch one of the most respected cattle operations in Southern Arizona by the 1950s. In 1959 the Buenos Aires Ranch, with its historic adobe and its Lake Aguirre, was sold and changed hands multiple times in the following 25 years. By 1984 the extensive ranch came under the control of Pablo Brener, a great Mexican industrialist of Lithuanian Jewish heritage who had many other investments in the U.S., including a hotel and supermarket chain in California managed from the offices of one of Brener’s companies in the Century City complex in Los Angeles. As most of the day-to-day operating decisions at the ranch were undertaken by the cowboys working there, the ranch was in many ways just another investment in Brener’s extensive portfolio. [16] Nevertheless, by the middle of the 1980s various environmental groups in Arizona such as the National Audubon Society and the Nature Conservancy worked to establish a wildlife refuge in the area to preserve the Altar Valley’s ecosystems, including a subspecies of quail known as the masked bobwhite quail. Many local residents feared the consequences of ending cattle operations at the Buenos Aires Ranch. They feared the end of cattle-raising at the ranch could negatively affect the Altar Valley’s economy (the De la Osa Ranch no longer raised cattle) and reduce employment opportunities in the area and potentially threaten the survival of the San Fernando Elementary School since half of its students were the children of cowboys who worked at the Buenos Aires Ranch. “The real endangered life form is not the ‘colinus ridgwayi’, otherwise known as the masked bobwhite, but the ‘homo sapiens’ who live and work in the Sasabe area.” Despite the opposition of various valley residents, Southern Arizona’s congressman Morris Udall helped assign congressional funds for the USFWS to purchase the ranch. Pablo Brener, always the financial visionary, rejected the initial $5 million offer by the USFWS and did not sell until the U.S. government paid $8.9 million for the ranch on February 20, 1985. Brener and his sons have maintained a low public profile over the years despite how their Grupo Xabre also bought the Mexican government-owned airline “Mexicana de Aviación” during its privatization during Carlos Salinas de Gortari’s administration. [17] Growing over the years through new property purchases, the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge today comprises 117,107 acres and has helped in growing the masked bobwhite quail population among other species. Besides the threat of new mineral discoveries in the region, the transit of undocumented immigrants and smugglers from the Mexican side of the international border threatens the refuge’s ecosystem. The harrowing migration of migrants crossing the border for new opportunities in the U.S. is a complex topic, but it is necessary to recognize the economic/political causes and the human impact of this migration on the environment. [18] An afternoon thunderstorm in July provides a bit of relief from the high summer temperatures in the Southern Arizona deserts. This rainbow touches the horizon on the eastern edge of the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge, the eastern limit of the Altar Valley. The elevation of Sasabe, Arizona measures 3,500 ft (or 1,067 meters) over sea level. The Altar Valley gradually loses elevation when traveling north. In Robles Junction (or Three Points), where State Route 286 ends, the elevation measures 2,540 ft (or 774 meters) over sea level. Our journey through the binational Altar Valley draws to a close near where it started in part one of the series – Baboquivari. The bell-shaped Baboquivari truly leaves its distinctive mark in the desert landscape of Arizona’s Altar Valley. The sacred mountain of the Tohono O’odham and a reference point for many undocumented migrants among others, Baboquivari bears witness to the rural, remote, and in many cases rough character of this important and historic corridor. The odyssey of the Serrano, Escalante, and Aguirre families – among many others – is just one example of the significant Mexican heritage in the history of the Altar Valley, which is in reality the northern half of a larger ecological and historical corridor. Although this binational and transcultural history is not well known in either Arizona or Mexico, the O’odham and Mexican legacy of the Altar Valley demonstrates the importance of these communities in the formation of Arizona and the inseparable cross-border roots of this region. NOTES:[1] Brady McCombs, “Border fence construction near Sasabe to start Monday,” Arizona Daily Star, August 23, 2007 (http://tucson.com/news/local/border/border-fence-construction-near-sasabe-to-start-monday/article_586533a8-b45d-54e7-b38a-c652b69415e0.html).

[2] “Sasabe, Arizona,” Arizona-Mexico Commission, http://www.azmc.org/border-communities/sasabe-arizona/ (accessed Dec. 12, 2017); Jonathan Clark, “CBP stats show big drop in local border-crossings,” Nogales International, December 20, 2011, http://www.nogalesinternational.com/news/cbp-stats-show-big-drop-in-local-border-crossings/article_28530fac-2aac-11e1-8f2e-0019bb2963f4.html (accessed Dec. 12, 2017); Arnie Maltz, et al, “Forecast and Planning Capacity for Nogales’s Ports of Entry,” ASU International Logistics and Productivity Improvement Lab, http://ilpil.asu.edu/research/supplychainlogistics-projects/forecast-and-capacity-planning-for-nogales%e2%80%99-ports-of-entry/, pg. 18; “U.S. Inspection Station-Sasabe, Arizona,” National Register of Historic Places Program (https://www.nps.gov/nr/feature/places/14000243.htm) [3] Russell True, Dude Ranching in Arizona (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia 2016), 86-91. [4] Don Vance, “Try Sasabe for a Quiet Snooze,” Tucson Daily Citizen, February 5, 1953. [5] Alberto Suarez Barnett, “¿Cuando fue fundado Nogales?” Anecdotas Historicas Sonorenses, February 19, 2017 (http://anecdotassonorenses.blogspot.com/2017/02/cuando-fue-fundado-nogales.html); Don Vance, “Try Sasabe for a Quiet Snooze,” Tucson Daily Citizen, February 5, 1953. [6] Don Vance, “Try Sasabe for a Quiet Snooze,” Tucson Daily Citizen, February 5, 1953; “State Highway Department Road Map of Arizona, 1935,” Arizona State Highway Department, 1935 (https://www.azdot.gov/docs/default-source/scenic-routes/az_st_hwy_dept_road_map_1935combo.pdf?sfvrsn=2); “Presumido Peak Quadrangle,” U.S. Geological Survey, 1943 (http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/topo/arizona/pclmaps-topo-az-presumido_peak-1941.jpg). [7] Lilia Urias, “Sasabe Postmistress,” Tucson Daily Citizen, February 21, 1941, pg. 9. [8] “Imperial Copper Company,” The Copper Handbook: A Manual of the Copper Industry of the World, (1911) 971 (https://books.google.com/books?id=M8pIAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA971&dq=puerto+lobos+sasco+railroad&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi9963wxoHYAhXK44MKHapIDTwQ6AEIMTAC#v=onepage&q=puerto%20lobos%20sasco%20railroad&f=false); Charles Zaremba, “Sonora: Railroads,”The Merchants and Tourists’ Guide to Mexico, Chicago: Althrop Publishing House (1883), 113 (https://books.google.com/books?id=9AIOAAAAIAAJ&pg=RA4-PA113&lpg=RA4-PA113&dq=puerto+lobos+sasabe+railroad&source=bl&ots=vENJOGK45B&sig=Cq3U-5Mpnn2CCfEQxQKAf523cT4&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi_lve1xIHYAhUd3YMKHfoKBQsQ6AEIQDAK#v=onepage&q=puerto%20lobos%20sasabe%20railroad&f=false); “Concesion para construir un ferrocarril en el estado de Sonora,” Boletín de la Oficina Internacional de las Repúblicas Americanas, Issue 30, P. 463 (https://books.google.com/books?id=dMg-AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA463&lpg=PA463&dq=ferrocarril+sasabe&source=bl&ots=HYF3yJvTDC&sig=Lz5EdNsvtDrhFDzy8DfeV2MMg3c&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwit5dbUkoHYAhVC0GMKHZyRCqYQ6AEIZTAN#v=onepage&q=ferrocarril%20sasabe&f=false) [9] “85633,” United States Zip Codes, https://www.unitedstateszipcodes.org/85633/, (accessed December 10, 2017); “85633,” American Fact Finder, U.S. Census Bureau, https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/community_facts.xhtml#; Daniel González, “Arizona border outpost one of the quietest in U.S.,” Arizona Republic, November 27, 2011 (http://archive.azcentral.com/news/articles/2011/11/15/20111115arizona-border-outpost-sasabe.html) [10] Daniel González, “Tiny Arizona border town full of strange stories,” Arizona Republic, Nov. 13, 2011 http://archive.azcentral.com/arizonarepublic/news/articles/20111112arizona-border-town-sasabe.html (accessed Dec. 10, 2017); Anna Chan, Sasabe Store Adobe & Wholesale Mesquite Firewood Review, Google, https://www.google.com/search?q=sasabe+store&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-8&client=firefox-b-1#lrd=0x86d46b940dc20b6f:0xc0d087ba85dfdd8e,1. [11] Daniel González, “Tiny Arizona border town full of strange stories,” Arizona Republic, Nov. 13, 2011 http://archive.azcentral.com/arizonarepublic/news/articles/20111112arizona-border-town-sasabe.html (accessed Dec. 10, 2017). Anna Chan, Sasabe Store Adobe & Wholesale Mesquite Firewood Review, Google, https://www.google.com/search?q=sasabe+store&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-8&client=firefox-b-1#lrd=0x86d46b940dc20b6f:0xc0d087ba85dfdd8e,1; Lilia Urias, “Sasabe Postmistress,” Tucson Daily Citizen, February 21, 1941, pg. 9. [12] Leslie Ernenwein, “Sasabe’s Owner Studies Sale of Border Town,” Tucson Daily Citizen, November 18, 1959, pg. 1; Jeff Smith, “The Sale of Sasabe is a Borderline Affair,” Tucson Daily Citizen, March 4, 1977, pg 1. [13] “San Fernando Elementary School, Sasabe, AZ 85633,” AZ HomeTownLocator, https://arizona.hometownlocator.com/schools/profiles,n,san%20fernando%20elementary%20school,z,85633,t,pb,i,1003027.cfm; “Meet our Staff,” San Fernando Elementary School District #35, http://www.sanfernando35.org/index.cfm?pID=13905, (accessed December 10, 2017). Daniel González, “Tiny Arizona border town full of strange stories,” Arizona Republic, Nov. 13, 2011 http://archive.azcentral.com/arizonarepublic/news/articles/20111112arizona-border-town-sasabe.html (accessed Dec. 10, 2017). [14] Fernando Serrano, “An Old Ranger,” Tucson Daily Citizen, February 21, 1941, pg. 9. [15] Betty Leavengood, “In the Land of Good Winds: An Informal History of Buenos Aires Ranch,” Journal of Arizona History, Vol. 47, no. 1 (Spring 2006), 2-12. [16] Betty Leavengood, “In the Land of Good Winds: An Informal History of Buenos Aires Ranch,” Journal of Arizona History, Vol. 47, no. 1 (spring 2006): 22-28; Jesus Sanchez and Martha Groves, “Boys Markets Gets $130.7-Million Bid for 54-Store Chain,” Los Angeles Times, March 2, 1988 (http://articles.latimes.com/1988-03-02/business/fi-321_1_supermarket-chain); Ralph King Jr., “Mexican contrarian: Pablo Brener quadrupled his family's fortunes during 1980's,” Forbes Magazine, Sept. 4, 1989; “Friends and Family, Mexican Style,” Wired, Oct. 1, 1995 (https://www.wired.com/1995/10/mexico/). [17] Betty Leavengood, “In the Land of Good Winds: An Informal History of Buenos Aires Ranch,” Journal of Arizona History, Vol. 47, no. 1 (spring 2006): 22-28; Jaime Santiago, “Pablo e Israel Brener Brener,” Expansion, 20 de septiembre de 2011 (http://expansion.mx/expansion/2011/09/14/pablo-e-israel-brener-brener); Elvira Concheiro, El gran acuerdo: gobierno y empresarios en la modernización salinista (Mexico, DF: UNAM, Instituto de Investigaciones Economicas, 1996), 85-88. [18] Leigh Ferrara, “Shifting Migration: Can a fence along the border clear up 25 million tons of trash and massive erosion in the Sonoran Desert? History says No,” Mother Jones, Sept. 29, 2006, http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2006/09/shifting-migration/#

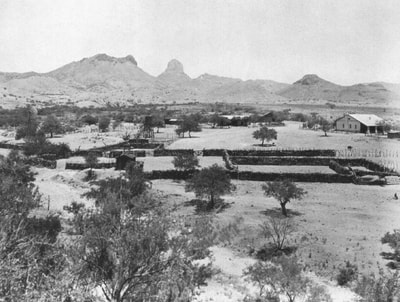

10 Comments

Christina Henry

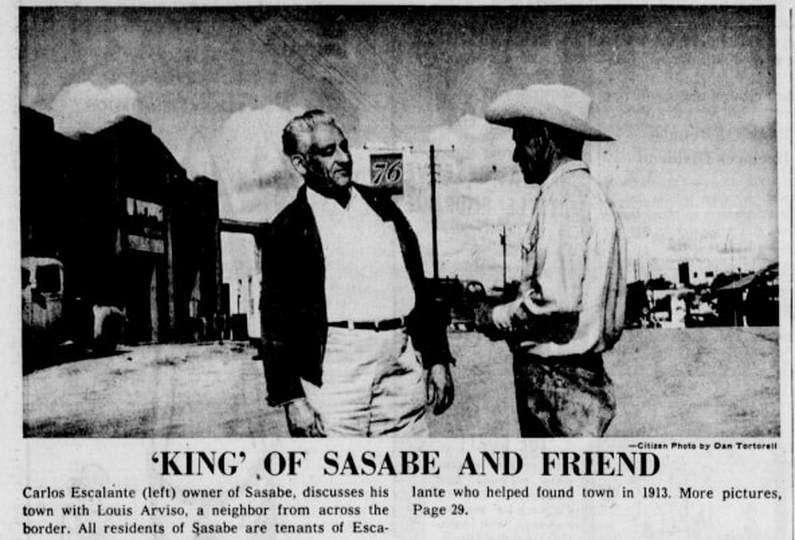

2/2/2019 08:12:09

Your website is a gem. I stumbled upon it while researching our family's genealogy. Ancestors were vaqueros from Caborca. Thank you so very much for providing some context to our records.

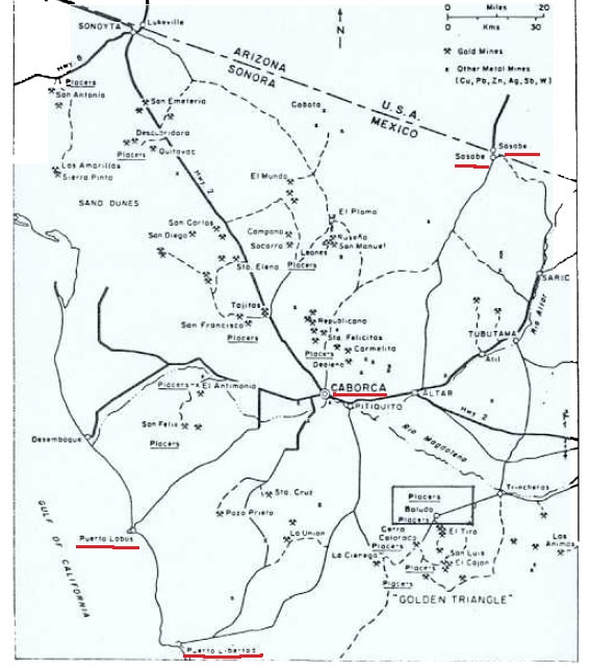

Reply

9/7/2019 21:35:38

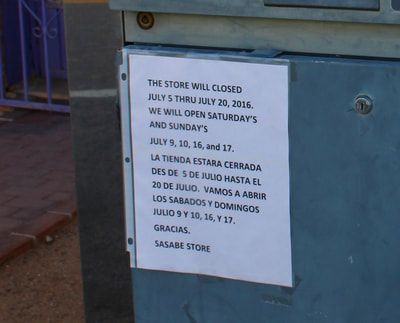

Christina,

Reply

Frank Grieco

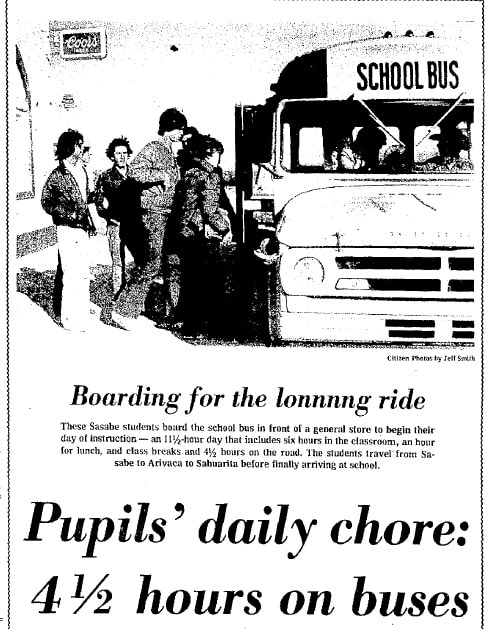

3/25/2019 16:18:10

I am involve with Church at Sasabe. How can I purchase a printed copy of this article?

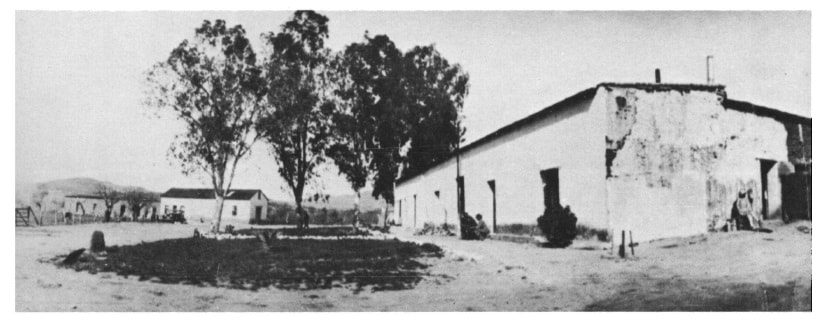

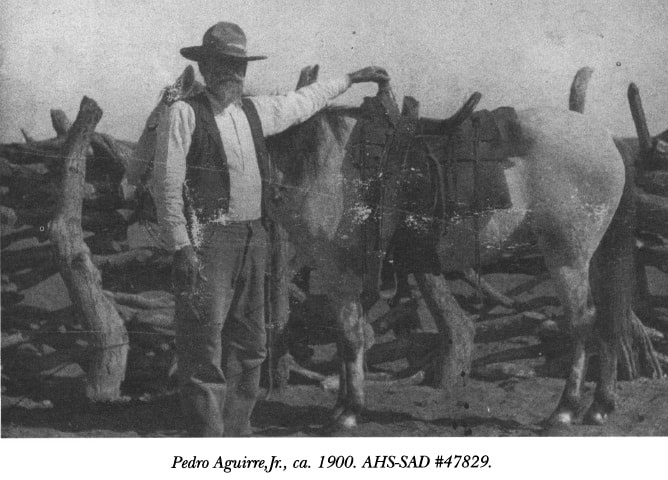

Reply

9/7/2019 21:39:07

Frank,

Reply

Natividad Cano

7/5/2021 17:51:05

I loved the article with so much information and history. I was burn in Sásabe, Sonora and lived in the Buenos Aires Ranch when my father worked there in the early 60s.

Reply

11/27/2021 12:00:29

Hi Natividad,

Reply

beth trenter

7/22/2021 17:00:06

Thank you for the amazing pictures and article. I lived in Sasabe when I was eight. My mom and I were located at the Santa Margarita Ranch where my mom helped the ranchers with their cattle. I went to school in a two room school house near there, but it was about an hour and a half bus ride each way. Sasabe is one of my favorite places on Earth. I loved my time there.

Reply

11/27/2021 12:03:18

Beth,

Reply

Dee Dee

8/22/2023 23:30:15

My grandfather was Clayton Vincent who was the foreman of the Buenos Aires ranch 1939 (I think) when he was just 20 years old. I have Been researching and looking at so many photos from my mom. It’s just so beautiful. Just explains why i love What i love And why i want to build fences w adobe and barns it’s in my blood. What a wonderful heritage to explore.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Carlos Parra

U.S.-Mexican, Latino, and Border Historian Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed